Last year's trip to America's heartland left us

hungry for more. This year's American Yankee Association convention

in Red Deer, Alberta, provided the perfect anchor for another flying vacation.

We used a rented Tiger.

Last year's trip to America's heartland left us

hungry for more. This year's American Yankee Association convention

in Red Deer, Alberta, provided the perfect anchor for another flying vacation.

We used a rented Tiger.

When we've flown west before, it seems we only had bad weather close to home. This trip started out that way too. We needed an instrument clearance to get away from Bridgeport, but were soon in the clear and on our way. We also found IFR weather on the day we arrived in Alberta, and we flew around a thunderstorm at the very end of the trip, about 40 miles from home.

But for most of the trip, we were in beautiful VFR weather, even though we had to change our route to arrange that. We had planned to visit Michigan's Upper Peninsula twice, but it was raining there at the time we had planned our second stop. That's a nice thing about travelling by light airplane. We just skipped that stop and flew to good weather instead.

We visited these airports and places:

We visited these airports and places:

Midland, Mich. - fuel

Calumet, Mich. - overnight

Pine River, Minn. - fuel

International Peace Garden, N.D. & Man.

Minot, N.D. - overnight

Havre, Mont. - fuel

Lethbridge, Alta. - fuel and Customs

Red Deer, Alta. - the convention site

Field, B.C. - overnight

Jasper, Alta. - overnight

Williston, N.D. - fuel and Customs

Medora, N.D. - overnight

Lake Itasca, Minn. - overnight

Iowa City, Iowa - overnight

Kent, Ohio - fuel

Milford, Conn. - home

Our first destination was Calumet, Michigan - a little too far for a comfortable day's run in a Tiger. So we left a day early and spent a night in Ithaca, N.Y., just to get a couple of hours' travel behind us.

Next morning, we were on our way. At our fuel stop in Midland, Mich., the lady running the FBO makes good brownies for her customers - a welcome surprise.

The Keweenaw Peninsula was once the copper capital of the

world. If a visitor didn't already know that, this ten-foot tree makes the

point. It's made entirely of copper, and graces the lobby of a hotel in

Calumet.

The Keweenaw Peninsula was once the copper capital of the

world. If a visitor didn't already know that, this ten-foot tree makes the

point. It's made entirely of copper, and graces the lobby of a hotel in

Calumet.

Calumet was the home of the Calumet & Hecla Copper Mining Company, which is

now preserved as the Calumet Unit of Keweenaw National Historical Park.

A few miles down the road near Hancock, the

Quincy Mine has been converted to

a museum. There are displays in the old engine house, which is the focus of

a tour down into the mine, seven stories below ground. One large

room houses a scale model of a mining town, including the trains that took

the copper to market.

A few miles down the road near Hancock, the

Quincy Mine has been converted to

a museum. There are displays in the old engine house, which is the focus of

a tour down into the mine, seven stories below ground. One large

room houses a scale model of a mining town, including the trains that took

the copper to market.

At first, we thought the smaller copper nugget was attached to the desk

because it didn't respond to gentle nudges. When we figured out that it

weighs nearly a hundred pounds, we also figured out that we could lift it.

The large copper boulder in the next room was raised from Lake Superior. It

weighs 17 tons, so nobody tried to lift it.

At first, we thought the smaller copper nugget was attached to the desk

because it didn't respond to gentle nudges. When we figured out that it

weighs nearly a hundred pounds, we also figured out that we could lift it.

The large copper boulder in the next room was raised from Lake Superior. It

weighs 17 tons, so nobody tried to lift it.

The Quincy Mining Company operated for a hundred years, from 1846 to 1945. It was one of the most successful mining operations ever, anywhere; it was called "Old Reliable" because it paid its investors a dividend every year until 1920. Because of declining prices, the mine stopped operating in 1931. If briefly resumed operation during World War II, but closed forever in 1945.

This is the Quincy #2 Shaft House, the world's tallest at

147 feet

above ground. It was built in 1908, and was used until the mine stopped

operating.

It was also the world's deepest - the shaft

extends 9260 feet

(92 "levels')

beneath the surface. The photo of the shaft house was taken from a couple

hundred feet away at the hoist house's engine room. This building housed the

Nordberg Steam Hoist, driven by

the world's largest steam-powered hoist engine.

This is the Quincy #2 Shaft House, the world's tallest at

147 feet

above ground. It was built in 1908, and was used until the mine stopped

operating.

It was also the world's deepest - the shaft

extends 9260 feet

(92 "levels')

beneath the surface. The photo of the shaft house was taken from a couple

hundred feet away at the hoist house's engine room. This building housed the

Nordberg Steam Hoist, driven by

the world's largest steam-powered hoist engine.

This engine turned the huge hoist drum you see here, which was connected to an

enormous pulley in the shaft house by lengths of

This engine turned the huge hoist drum you see here, which was connected to an

enormous pulley in the shaft house by lengths of

The

last photo (larger, more readable version

here) shows a diagram of the inside of the shaft house. Large buckets

called "skips" are raised with their loads, balanced so they will tip over

easily to release the load.

The

last photo (larger, more readable version

here) shows a diagram of the inside of the shaft house. Large buckets

called "skips" are raised with their loads, balanced so they will tip over

easily to release the load.

Some old skips are on display outside the shaft house. A man can stand

inside one of these without bending.

There is also a motley collection of other unidentified equipment.

Some old skips are on display outside the shaft house. A man can stand

inside one of these without bending.

There is also a motley collection of other unidentified equipment.

The Man Car (right side) was introduced in 1892. It could carry 30 men at a

time into or out of the mine, three per bench.

This was much more convenient than climbing

ladders, an earlier mode of transport.

The Man Car (right side) was introduced in 1892. It could carry 30 men at a

time into or out of the mine, three per bench.

This was much more convenient than climbing

ladders, an earlier mode of transport.

Besides housing the enormous steam engine, the hoist building was unusual in

its own right. Built in 1918, it was one of the first large buildings built

of reinforced concrete. Although it is nearly five stories high, there are

no interior support columns. The building was used as a showplace for

visitors, incorporating a lot of brass for the staff to keep shining

brightly. Much of the brass has been replaced with iron since the mine shut

down, but some remains on the rail to the spiral staircase. The dials at the

top of the staircase were used for the operator to tell exactly where the

cars were on the two-mile-long hoist just up the hill.

Besides housing the enormous steam engine, the hoist building was unusual in

its own right. Built in 1918, it was one of the first large buildings built

of reinforced concrete. Although it is nearly five stories high, there are

no interior support columns. The building was used as a showplace for

visitors, incorporating a lot of brass for the staff to keep shining

brightly. Much of the brass has been replaced with iron since the mine shut

down, but some remains on the rail to the spiral staircase. The dials at the

top of the staircase were used for the operator to tell exactly where the

cars were on the two-mile-long hoist just up the hill.

Since the mine closed, groundwater has slowly filled the lower 85 levels,

making them inaccessible (there are no diving tours). The seventh level is

drained by a large adit, which is used for access to the underground tour.

We got there by a cog railcar, an adventure in itself. The tram negotiates

a very steep hill, relying on the third rail to keep it from slipping in

either direction.

Since the mine closed, groundwater has slowly filled the lower 85 levels,

making them inaccessible (there are no diving tours). The seventh level is

drained by a large adit, which is used for access to the underground tour.

We got there by a cog railcar, an adventure in itself. The tram negotiates

a very steep hill, relying on the third rail to keep it from slipping in

either direction.

Our guide explained how the mine was laid out, and answered questions about

things like those straps that are all over the place, holding the walls and

ceilings in place. An exhibit back in the hoist house shows how the straps

are attached. Sort of like overgrown Molly bolts.

Our guide explained how the mine was laid out, and answered questions about

things like those straps that are all over the place, holding the walls and

ceilings in place. An exhibit back in the hoist house shows how the straps

are attached. Sort of like overgrown Molly bolts.

On the way into the mine, we passed a chamber that had been used as a classroom by Michigan Tech's Mining Department. Michigan Tech was founded in 1885 as the Michigan Mining School to train engineers for work in the copper mines. Today, the school no longer offers a bachelor's degree in Mining Engineering, although there are graduate programs.

The larger drill on the left required two men to operate, and had a history

of making both of them sick because of the amount of rock dust it produced.

When the one-man drill (right) was introduced, it also had a means to remove

the rock dust as soon as it was produced, greatly improving the health of the

miners who used it. But the men didn't like it because only half the

previous work force was needed for drilling, which eliminated jobs. The

drills were used to make the holes shown in the second photo, to insert

dynamite sticks for blasting.

The larger drill on the left required two men to operate, and had a history

of making both of them sick because of the amount of rock dust it produced.

When the one-man drill (right) was introduced, it also had a means to remove

the rock dust as soon as it was produced, greatly improving the health of the

miners who used it. But the men didn't like it because only half the

previous work force was needed for drilling, which eliminated jobs. The

drills were used to make the holes shown in the second photo, to insert

dynamite sticks for blasting.

Two more thriving mining companies operated in Red Jacket, which is now known

as Calumet. They combined their names when they merged in 1871 to form the

Two more thriving mining companies operated in Red Jacket, which is now known

as Calumet. They combined their names when they merged in 1871 to form the

This former administration building is the history center.

Alexander Agassiz, son of noted geologist Louis Agassiz, is remembered

(same building, other side) because

he was pivotal in the early success of the

This former administration building is the history center.

Alexander Agassiz, son of noted geologist Louis Agassiz, is remembered

(same building, other side) because

he was pivotal in the early success of the

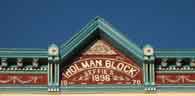

Stores in the downtown historic district have been restored to their

late-19th-century detail.

Stores in the downtown historic district have been restored to their

late-19th-century detail.

The mines shipped their product by rail, even if it was only a short distance

to Lake Superior. To keep the tracks clear, they used these behemoth

snowplows. These are needed in the Keweenaw, which gets more snow than

anywhere else in the country, east of the Rocky Mountains.

A few miles up the road in Phoenix, there is a "thermometer" to

keep track of annual snowfall, from a "mere"

161 inches

in 1999-2000 to a record 390 inches

in 1978-79. Average annual snowfall is 241

inches.

The mines shipped their product by rail, even if it was only a short distance

to Lake Superior. To keep the tracks clear, they used these behemoth

snowplows. These are needed in the Keweenaw, which gets more snow than

anywhere else in the country, east of the Rocky Mountains.

A few miles up the road in Phoenix, there is a "thermometer" to

keep track of annual snowfall, from a "mere"

161 inches

in 1999-2000 to a record 390 inches

in 1978-79. Average annual snowfall is 241

inches.

The snowplow is not the only unusual vehicle to be seen in Calumet.

The snowplow is not the only unusual vehicle to be seen in Calumet.

Calumet's twin city, Laurium, is the birthplace of George Gipp. Gipp was

Notre Dame's famous All-American back whose deathbed quote was the inspiration

for Knute Rockne's famous "win one for the Gipper" speech. Laurium has a

small memorial park devoted to the memory of their most famous native son.

Calumet's twin city, Laurium, is the birthplace of George Gipp. Gipp was

Notre Dame's famous All-American back whose deathbed quote was the inspiration

for Knute Rockne's famous "win one for the Gipper" speech. Laurium has a

small memorial park devoted to the memory of their most famous native son.

"I've got to go, Rock. It's all right. I'm not afraid. Some time, Rock, when the team is up against it, when things are wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, ask them to go in there with all they've got and win just one for the Gipper. I don't know where I'll be then, Rock. But I'll know about it, and I'll be happy."

This line may have later helped an actor get to the White House.

Douglass Houghton was the man who found all that copper that brought

prosperity to the Keweenaw. He too has a memorial. A talented geologist,

he was selected by the noted explorer Henry Schoolcraft for expeditions around

Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi valley. Houghton was also trained as

a physician, but his main love and major effort was in geology. When Michigan

became a State in 1837, Houghton was appointed to organize a geological

survey. He retained his title as State Geologist for the remainder of his

life, which was cut short by a drowning accident in Lake Superior near this

monument in Eagle River.

Douglass Houghton was the man who found all that copper that brought

prosperity to the Keweenaw. He too has a memorial. A talented geologist,

he was selected by the noted explorer Henry Schoolcraft for expeditions around

Lake Superior and the upper Mississippi valley. Houghton was also trained as

a physician, but his main love and major effort was in geology. When Michigan

became a State in 1837, Houghton was appointed to organize a geological

survey. He retained his title as State Geologist for the remainder of his

life, which was cut short by a drowning accident in Lake Superior near this

monument in Eagle River.

We passed Eagle River on our way from Calumet to Copper Harbor, where we

hoped to tour the

lighthouse there. Copper Harbor isn't really the end of

the world, but it's at the end of the last road on the Keweenaw Peninsula.

It's as far north as you can go in Michigan without getting on the ferry to

Isle Royale, which is truly remote.

We passed Eagle River on our way from Calumet to Copper Harbor, where we

hoped to tour the

lighthouse there. Copper Harbor isn't really the end of

the world, but it's at the end of the last road on the Keweenaw Peninsula.

It's as far north as you can go in Michigan without getting on the ferry to

Isle Royale, which is truly remote.

Here's the town of Copper Harbor and its lighthouse; first from Brockway Mountain Road, and then as seen from the town piers. In the first photo, the lighthouse is east (right) of the harbor entrance; the pier is near the buildings at the left in this photo. The whitecaps hint at the small craft warnings that kept us from getting a tour of the lighthouse that day.

Since we couldn't get to the lighthouse, we contented ourselves with exploring Fanny Hooe Creek near Ft. Wilkins State Park, where we at least got a little closer view of the lighthouse. Fanny who?? According to legend, she lived at Ft. Wilkins in 1846, and vanished without a trace while picking berries near the creek that now bears her name.

We returned to Calumet via Lake Shore Drive, with spectacular trails on Lake

Superior. Copper isn't the only abundant mineral here; the red

color of the rocks is from iron.

We returned to Calumet via Lake Shore Drive, with spectacular trails on Lake

Superior. Copper isn't the only abundant mineral here; the red

color of the rocks is from iron.

Some of these rocks are very decorative, featured in buildings at the

mine and in the mining towns in the area.

Some of these rocks are very decorative, featured in buildings at the

mine and in the mining towns in the area.

One of the rocks was trampled by Bigfoot. Or at least marked by someone with

a big foot.

One of the rocks was trampled by Bigfoot. Or at least marked by someone with

a big foot.

This tree seems to be rising above its humble roots. It reminds me a bit of

another tree

we saw in Yellowstone National Park, on

another trip

a few years ago.

This tree seems to be rising above its humble roots. It reminds me a bit of

another tree

we saw in Yellowstone National Park, on

another trip

a few years ago.

There's a much larger photo of the new tree

here, or maybe you just want a closer look at its

roots.

When we stopped for a

pasty in Copper Harbor, it was comforting to learn that

we were on the right road if we wanted to get to Florida.

When we stopped for a

pasty in Copper Harbor, it was comforting to learn that

we were on the right road if we wanted to get to Florida.

The photo at right was taken just after 9 PM. We were on our way to Eagle

Harbor to wait for 10:00, which is when the sun finally sets here in July.

This part of Michigan is in the Eastern time zone, but it's west of Chicago.

The photo at right was taken just after 9 PM. We were on our way to Eagle

Harbor to wait for 10:00, which is when the sun finally sets here in July.

This part of Michigan is in the Eastern time zone, but it's west of Chicago.

on to the International Peace Garden

Calumet

Peace Garden

Drumheller

Red Deer

Convention

Bow River Pkwy

Lake Louise

Moraine Lake

Field

Yoho NP

Icefields Parkway

Jasper

Home