Home

Amana

Sioux City

Rawlins

Rockies

Moab

Canyonlands

Arches

Salt Lake

Sutter Creek

Big Trees

Sacramento

Convention

Lava Beds

Crater Lake

Beaver Island

to the story's beginning back to Sioux City

West of Alliance, the terrain began to rise in earnest, and we encountered some light turbulence - the only part of the trip that even resembled a rough ride (it was early afternoon by now). We landed at Rawlins shortly after 3 PM. At 6813 feet above sea level, this was our highest-elevation landing (and takeoff).

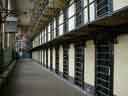

Rawlins is the home of the old

Wyoming State Penitentiary. The original pen was

in use from 1901 to 1981, when a new prison was opened, also in Rawlins. The

old prison is a National Registered Landmark, and may be seen by guided tour.

Rawlins is the home of the old

Wyoming State Penitentiary. The original pen was

in use from 1901 to 1981, when a new prison was opened, also in Rawlins. The

old prison is a National Registered Landmark, and may be seen by guided tour.

Of course we took the tour. There's a small museum that may be seen without

the tour, but it's only a small fraction of the place.

Of course we took the tour. There's a small museum that may be seen without

the tour, but it's only a small fraction of the place.

The tour begins with an explanation of the Julian Gallows, which Wyoming used

to execute nine prisoners before replacing it with a gas chamber in 1936.

Invented by a Cheyenne architect, this machine is a Rube Goldberg-like

contraption.

One end of a rope is tied to a support that works like a trick knee. The

other end is attached through a pulley to a balance weight just outside the

scene here. The weight is balanced by a can of water. When the prisoner

steps on the trap door, another cord pulls a plug out of the can. Water runs

out until the balance weight has lowered far enough to pull the support beam

so it collapses suddenly, opening the trap door and dropping the condemned

man.

Invented by a Cheyenne architect, this machine is a Rube Goldberg-like

contraption.

One end of a rope is tied to a support that works like a trick knee. The

other end is attached through a pulley to a balance weight just outside the

scene here. The weight is balanced by a can of water. When the prisoner

steps on the trap door, another cord pulls a plug out of the can. Water runs

out until the balance weight has lowered far enough to pull the support beam

so it collapses suddenly, opening the trap door and dropping the condemned

man.

The mechanism wasn't meant to be humane, so much as to spare Wyoming citizens

from having to pay a hangman — the prisoner was his own executioner.

Of the nine men executed on this gallows from 1912–1933,

none fell far and hard enough to break his neck; they all died by suffocation.

This "prisoner" is waiting for a visitor.

This "prisoner" is waiting for a visitor.

Here's Cell Block A and one of its cells - looking in, and looking out.

This is what solitary confinement would look like from the inside if the

prisoner had a flash camera. There's no other light in the cell.

This is what solitary confinement would look like from the inside if the

prisoner had a flash camera. There's no other light in the cell.

Death row cells are behind two sets of bars. Each cell has a photo of

an inmate who had spent his last days in that cell.

This is the trap door for the Julian Gallows. The photos are all the

prisoners executed here and in the gas chamber. Before stepping onto the

trap door, the prisoner was told to look out the window for one last view of

the world outside.

Wyoming started using cyanide gas to execute condemned prisoners in 1936.

For quality control, they tested the apparatus on a pig before each

execution.

A couple of views in the exercise yard. The tree is a Russian Olive, which I

know as a bush. I've never seen one more than eight feet tall before this.

A couple of views in the exercise yard. The tree is a Russian Olive, which I

know as a bush. I've never seen one more than eight feet tall before this.

The prisoners were allowed to paint - on media, on the walls, just about

anywhere. The last painting was meant as an admonishment to "stay on the

right side of the tracks."

The prisoners were allowed to paint - on media, on the walls, just about

anywhere. The last painting was meant as an admonishment to "stay on the

right side of the tracks."

We got an early start for the flight from Rawlins to Moab. We flew over several oil wells, and then the terrain began to rise again, offering very few options for a forced landing. We followed the Green River through the Dinosaur National Monument, which straddles the Colorado-Utah state line. The last photo shows a road in this park. It leads to the turn-around at Echo Park Overlook, Harpers Corner. It looks like it would be a pretty tough drive to get up there. It's 7625 feet above sea level.

Chained to Mother Earth at Moab, Utah. The Canyonlands airport has a very

attractive terminal building.

If we had flown just fifteen minutes beyond Moab, we might have landed at

this airstrip instead of driving to it. It's the

Needles Outpost

runway,

next to Canyonlands National Park. The Outpost is a popular spot for fly-in

lunches, and sometimes for campers. It's 4500 feet long, which is adequate

but not overly long, almost 5000 feet above sea level on a hot day. We

needed the car, anyway.

If we had flown just fifteen minutes beyond Moab, we might have landed at

this airstrip instead of driving to it. It's the

Needles Outpost

runway,

next to Canyonlands National Park. The Outpost is a popular spot for fly-in

lunches, and sometimes for campers. It's 4500 feet long, which is adequate

but not overly long, almost 5000 feet above sea level on a hot day. We

needed the car, anyway.

In Moab, we stayed at an eclectic B&B with a fresh-water spring on the

property, a rarity in such a dry place.

In Moab, we stayed at an eclectic B&B with a fresh-water spring on the

property, a rarity in such a dry place.

It also has a small collection of

Volkswagen buses, one of which actually runs.

And you might be able to go

for a log ride. if you only knew how.

And you might be able to go

for a log ride. if you only knew how.

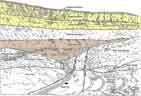

Although we were here to see two parks, even the drive into Moab offered scenic delights. It runs through the Moab Fault, seen here from a viewpoint in Arches National Park.

Caution: this photo is very wide (there's a smaller version here).

A dramatic break in the earth's surface occurred here about six million years

ago. Under intense pressure, unable to stretch, the crust cracked and

shifted. The highway parallels this fracture line.

After the rock layers shifted, the east wall of the canyon (from where the

photo was taken) ended up more than 2600 feet lower than the west side.

The west side of the Moab Fault is an anticline (layers scrunched up)

exposing several layers that were deposited when thie area was at the bottom

of a prehistoric ocean. Notice how the Chinle Formation slopes away from the

Wingate Sandstone above it. The Wingate is harder, acting like a protective

hat. A few miles south of here, we'll see a dramatic example of this

selective erosion just before we get to the Needles District.

The west side of the Moab Fault is an anticline (layers scrunched up)

exposing several layers that were deposited when thie area was at the bottom

of a prehistoric ocean. Notice how the Chinle Formation slopes away from the

Wingate Sandstone above it. The Wingate is harder, acting like a protective

hat. A few miles south of here, we'll see a dramatic example of this

selective erosion just before we get to the Needles District.

– diagram adapted from

Lohman, S.W., and Stacy, John R.,

The Geologic Story of Arches National Park,

U.S. Dept. of Interior, 1975.

Wilson Arch is on Route 191, just a few miles south of Moab.

It's Entrada sandstone, a layer that has already eroded from the high side of

the Moab Fault on the other side of the highway.

We planned to visit two national parks while we were in Moab. First stop was

the Needles in

Canyonlands National Park.

Newspaper Rock is on the access road into

the Needles. The sign nearby tells us that it...

We planned to visit two national parks while we were in Moab. First stop was

the Needles in

Canyonlands National Park.

Newspaper Rock is on the access road into

the Needles. The sign nearby tells us that it...

...is a petroglyph panel etched in sandstone that records approximately 2000

years of early man's activities. Prehistoric peoples, probably from the

Archaic, Basketmaker, Fremont and Pueblo cultures, etched on the rock from BC

time to AD 1300. In historic times, Utah and Navajo tribesmen, as well

as Anglos, left their contributions.

There are no known methods of dating rock art. In interpreting the figures

on the rock, scholars are undecided as to their meaning or have yet to

decipher them. In Navajo, the rock is called Tse' Hane' (rock that

tells a story).

Unfortunately, we do not know if the figures represent story telling,

doodling, hunting magic, clan symbols, ancient graffiti or something else.

Without a true understanding of the petroglyphs, much is left for individual

admiration and interpretation.

Leaving Newspaper Rock, we headed for the

Needles. This scene includes

Wooden Shoe Arch (third formation from the left), which we'll see closer in a

few moments.

Leaving Newspaper Rock, we headed for the

Needles. This scene includes

Wooden Shoe Arch (third formation from the left), which we'll see closer in a

few moments.

The Needles are a series of spires

formed out of a red and

white sandstone layer called Cedar Mesa Sandstone, which makes up

most of the rock features in the Needles District of the

Canyonlands Park. This 245 to 286 million year old layer was

once a dune field on the eastern edge of a shallow sea that

covered what is California, Nevada and western Utah today. Sand

was blown in from this direction and formed the white bands in

the Cedar Mesa Sandstone. The red bands came from sediment

carried down by streams from a mountainous area near where Grand

Junction Colorado, is today. These layers of sand were laid down on top of

each other and created the distinctive rocks seen in the Needles District.

Starting about fifteen million years ago, the Colorado Plateau

was pushed up thousands of feet. Rivers, such as the Colorado

and the Green, cut down and carved deep canyons. Water, the

primary force of erosion, eats away or weathers rock by attacking

the cement holding the sand grains together. During

storms, rushing water knocks loose sand and rocks as it flows

down washes, causing additional erosion. The water naturally acts

faster on areas of weakness within the rock, such as fractures

and cracks. The Needles occur in an area with many fractures

called joints.

The joints were formed in two different ways. The first was

the Monument uplift, which begins around the Needles District and

trends slightly southwest all the way to Monument Valley. This

uplift caused brittle, surface rock like the Cedar Mesa Sandstone

to crack as it was bent upward, forming a set of joints in a

northeast-southwest direction.

A thick salt layer underneath the Needles district, known as the

Paradox Formation, is the second cause of joint formation. The

salt is flowing slowly toward the Colorado River and dragging the

overlying layers with it. As the upper layers became stretched,

they also fractured into joints. This action created a set of

joints running northeast-southwest. In the Needles area, these

two joint sets meet and form square blocks of rock between the

joints. As water widened the joints, the squares were sculpted

into pillars and spires that are today the Needles of

Canyonlands.

These structures are outside the park boundary, but they are no less

striking than the formations inside.

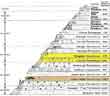

The diagram shows when several layers of rock were deposited in this area.

Over the past few million years, about half of them have eroded away from

this area. On the access road, we're somewhere in the middle of the Chinle

formation, which arrived here about 200 million years ago. The two Six

Shooter Peaks are named for their Wingate sandstone spires, which reminded

explorers of revolvers pointed up. This layer is harder than the underlying

Chinle Formation that composes the conical bases of the peaks. The harder

layer sheielded the peaks a bit from erosion, leaving the distinctive shapes

we see here.

Essentially the same process formed Chimney Rock in Nebraska (near Carhenge),

but that better-known structure is only about thirty mllion years old.

These structures are outside the park boundary, but they are no less

striking than the formations inside.

The diagram shows when several layers of rock were deposited in this area.

Over the past few million years, about half of them have eroded away from

this area. On the access road, we're somewhere in the middle of the Chinle

formation, which arrived here about 200 million years ago. The two Six

Shooter Peaks are named for their Wingate sandstone spires, which reminded

explorers of revolvers pointed up. This layer is harder than the underlying

Chinle Formation that composes the conical bases of the peaks. The harder

layer sheielded the peaks a bit from erosion, leaving the distinctive shapes

we see here.

Essentially the same process formed Chimney Rock in Nebraska (near Carhenge),

but that better-known structure is only about thirty mllion years old.

– diagram adapted from Sandra Hinchman's

Hiking the Southwest's Canyon Country,

3d ed., Mountaineers Books, Seattle, 2004, pg. 18

Wooden Shoe Arch. We learned about how arches are formed and destroyed a day

after seeing this park, at

Arches

National Park.

Wooden Shoe Arch. We learned about how arches are formed and destroyed a day

after seeing this park, at

Arches

National Park.

About 300 million years ago, this area was covered by an inland sea. As the

water evaporated, it left behind a great salt basin into which many layers of

sediment were deposited. Here, red sediments from the mountains to the East

interfingered with white coastal deposits. These sediments were later

transformed into the red and white sandstone of the Cedar Mesa formation that

is the floor of the Needles District.

The buried salt, which flows under pressure and is dissolved by ground water,

shifted under the sandstone, causing it to fracture. Weathering along the

fractures carved Wooden Shoe Arch, and the other arches, spires, knobs, and

fins that we see today.

Turn around after looking at the Wooden Shoe Arch, and you see Squaw Butte.

Like all of Canyonlands National Park, and unlike the Six Shooter Peaks, it's

above the Monument Uplift. Imagine a fist pushing up most of southern Utah

from below, and you get the idea. The structures in Canyonlands are Cedar

Mesa Sandstone, about 150 million years older than the Six Shooters. When

this area was an ocean floor, Canyonlands was about 2500 feet below the level

of the Six Shooters.

Turn around after looking at the Wooden Shoe Arch, and you see Squaw Butte.

Like all of Canyonlands National Park, and unlike the Six Shooter Peaks, it's

above the Monument Uplift. Imagine a fist pushing up most of southern Utah

from below, and you get the idea. The structures in Canyonlands are Cedar

Mesa Sandstone, about 150 million years older than the Six Shooters. When

this area was an ocean floor, Canyonlands was about 2500 feet below the level

of the Six Shooters.

In the very center of the first picture, there is a small cave in deep

shadow, visible from the roadside. This is an Ancestral Puebloan granary

tucked into a ledge above a dry wash, built 800 to 1000 years ago.

Canyonlands National Park has dozens of similar structures, but few

dwellings. This suggests that early inhabitants of the area farmed

intensively, but lived here only seasonally.

In the very center of the first picture, there is a small cave in deep

shadow, visible from the roadside. This is an Ancestral Puebloan granary

tucked into a ledge above a dry wash, built 800 to 1000 years ago.

Canyonlands National Park has dozens of similar structures, but few

dwellings. This suggests that early inhabitants of the area farmed

intensively, but lived here only seasonally.

Scenes from the auto road through the Needles District.

Pothole Trail offers dozens of examples.

Potholes are naturally occurring basins or pools in sandstone

that collect rainwater and wind-blown sediment. These potholes

harbor organisms that are able to survive long periods of

dehydration, and also serve as a breeding ground for many desert

amphibians and insects. Potholes range from a few millimeters to a few meters

in depth, and even the smallest potholes may harbor microscopic invertebrates.

From an NPS

web site,

Pothole Trail offers dozens of examples.

Potholes are naturally occurring basins or pools in sandstone

that collect rainwater and wind-blown sediment. These potholes

harbor organisms that are able to survive long periods of

dehydration, and also serve as a breeding ground for many desert

amphibians and insects. Potholes range from a few millimeters to a few meters

in depth, and even the smallest potholes may harbor microscopic invertebrates.

From an NPS

web site,

To survive in a pothole, organisms must endure extreme fluctuations in several environmental factors. Surface temperatures vary from 140 degrees Fahrenheit in summer to below freezing in winter. As water evaporates, organisms must disperse to larger pools or tolerate dehydration and the drastic physical and chemical changes that accompany it.

The most extreme conditions exist when a pothole is dry. In addition to the wide temperature fluctuations, ultraviolet light from the sun can damage body tissues. Many aquatic organisms are adapted to acquiring oxygen through water and suffer when exposed to air. Pothole organisms have three main ways of dealing with drought.

"Drought escapers" are winged insects, amphibians and invertebrates that breed in potholes but cannot tolerate dehydration (e.g. mosquitoes, adult tadpole and fairy shrimp, spadefoot toads). In some cases, adults live in permanent water sources or on land and travel to temporary pools to mate and lay eggs. If the pool dries out before the young mature, they die. In the case of tadpole, fairy and clam shrimp, adults must lay their drought-tolerant eggs before the pool dries up.

"Drought resistors" (e.g. snails, mites) have a dormant stage resistant to drying out. These animals have a waterproof layer like a shell or exoskeleton that prevents body tissues from losing too much water while a pool is dry. By burrowing, these animals are able to seal themselves in the layers of fine mud that often coat the bottom of potholes and form an impermeable crust.

"Drought tolerators" (e.g. rotifers, tadpole and fairy shrimp eggs) are able to tolerate a loss of up to 92 percent of their total body water. This remarkable process, known as "cryptobiosis," is made even more remarkable by the fact that many cryptobiotic species can be rehydrated and become fully functional in as little as half an hour. Cryptobiosis is accomplished by a command center that remains hydrated while substituting sugar molecules for water throughout the rest of the body. This transfer maintains the structure and elasticity of an organism's cells during long periods of drought, and enables the organism to withstand the climatic extremes of the desert. In fact, brine shrimp have been hatched from cryptobiotic cysts that endured a flight on the outside of a spacecraft. Many tolerators have only one stage in their life cycle (e.g. egg, larva) that can survive desiccation, and will die if a pool dries up during another phase.

Pothole organisms not only have to endure dry spells, but also must evaluate conditions and decide when to break dormancy. Desert precipitation falls at irregular intervals, and once water enters a pothole there is no guarantee that there is enough for an organism to complete its life cycle. Most organisms living in potholes have very short life cycles, as brief as ten days, reducing the time water is required and allowing them to live in the shallow pools. Even vertebrates such as toads, which are found in other environments, display shorter development times when found in potholes.

However, the presence of water may not be the only cue used by eggs and dormant life forms to activate. Oxygen content, temperature, and other physical and chemical factors of the water may be evaluated. Some organisms produce different types of eggs that hatch on different cues; others lay eggs in different areas so that they experience slightly different environmental conditions. The net result is that not all eggs hatch at once and the species has a better chance of survival. After a pothole fills with water, the small ecosystem experiences many other changes. Water temperatures can be very high, while oxygen levels can be very low. As the pool shrinks from evaporation, its salinity increases and the pH changes. Many organisms are capable of surviving wide fluctuations in these factors, but for some these changes are an indication that the time for dormancy is near.

Here's an example of life in a pothole. It also shows cryptobiotic soil, a

major geological feature of Arches National Park.

Some other scenes from the trail at Pothole Point.

Here's a teaser view of Islands in the Sky, in the background. What's that?

Here's a teaser view of Islands in the Sky, in the background. What's that?

Canyonlands National Park surrounds the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers. These rivers naturally divide the park into three sections. You can't get from one section to the other easily by car (no bridges), but you can see. This is a view of Islands in the Sky, generally considered to be the most accessible part of the park. These are buttes that haven't turned into needles yet. That will take a few thousand years or more.

It isn't possible to show the Needles in a normal photograph. This distant

view of Chesler Park is very wide (there's a smaller version

here).

It isn't possible to show the Needles in a normal photograph. This distant

view of Chesler Park is very wide (there's a smaller version

here).

on to Arches

Amana

Sioux City

Rawlins

Rockies

Moab

Canyonlands

Arches

Salt Lake

Sutter Creek

Big Trees

Sacramento

Convention

Lava Beds

Crater Lake

Beaver Island

Home