In 2000, my company acquired limited rights to software that had been written by another company in Manchester, England. Things were going well enough, until the other company was bought by one of our competitors. Suddenly, the transfer of information that usually goes along with an acquisition like this, took a major change in attitude. What had formerly been a lesson, now became more like a cross-examination at a very contentious trial.

As part of the proceedings, I was sent to England six times that year, about once a month beginning in July 2000. It was my job to learn as much as possible from people who didn't want me to learn anything at all, now that I represented a competitor.

Business travel isn't the dream trip that many people think it is. The traveller spends a lot of time away from home and family. If you need to be at the other end of a business trip from Monday through Friday, then your Sunday before and Saturday after are lost to travel. You get to spend a lot of time on airline cattle-cars, in business hotels that are convenient to work but not to tourism and entertainment, and in factories.

Where there's a will, there's a way. My colleagues and I still managed to see quite a few of the sights in and around Manchester.

Manchester and Birmingham compete for the title of the second largest city in the United Kingdom; after London, of course. Birmingham has more people within city limits, but Manchester is the center of a much larger metropolitan area.

So there's a lot to see, if one can arrange it outside of working hours. We did manage to arrange it.

After one trip, I also stayed an extra week while Barbara joined me for a whirlwind tour of England. We didn't have time to explore anything in depth, but we managed to see an impressive amount of this land that has such strong historical and cultural ties to the United States and Canada. There was an unusual turn of events in this part of the world. We had good luck with the weather, and got to see several interesting things in a very short time.

Between Barbara's visit and my solo excursions, we saw quite a few places:

Between Barbara's visit and my solo excursions, we saw quite a few places:

Powfoot, Scotland

Mold, Wales

Llanfair PG, Wales

Holyhead, Wales

Willowford — Hadrian's Wall

Castlerigg — Lake District

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

Airports are wonderful places, if you look at them in the right way. An airport is a magic portal to another world. You go in at one end and emerge somewhere completely different, limited only by your imagination and your budget. If you walk through this gate, your airplane deposits you in Pittsburgh. Walk through that gate thirty feet away, and you end up in Tokyo.

As you drive into Manchester's airport, they tell you this →

As you drive into Manchester's airport, they tell you this →

But if you fly into Manchester from anywhere else in the world, they let you

know that the gateway also leads to all the North of England has to offer.

Here's the other side of the same arch.

But if you fly into Manchester from anywhere else in the world, they let you

know that the gateway also leads to all the North of England has to offer.

Here's the other side of the same arch.

For Barbara and me, the airport was the gateway not only to the North, but to all of Great Britain.

These photos illustrate typical weather. England is not exactly famous for blue skies and sunshine. My colleague read a book during one of our trips that began with the phrase,

"It was a typical rainy Monday in Manchester…"

This is a data flow diagram for part of the software that our company had

bought. We were supposed to get a thorough explanation of it.

This is a data flow diagram for part of the software that our company had

bought. We were supposed to get a thorough explanation of it.

It outlines the information flow in the product we had paid for, but even this was a lot more than the other company wanted us to know. They were not very happy that I wanted to photograph this diagram, but they knew it was our legal property so nobody tried to stop me. Getting the "footnotes," however, was a very different matter.

Polly was our official hostess. Personally, she was very likable and offered

a wealth of advice for touring in Manchester, Cheshire, and the Lake District.

Polly was our official hostess. Personally, she was very likable and offered

a wealth of advice for touring in Manchester, Cheshire, and the Lake District.

Professionally, she was the consummate example of an adversary in a court of law. It was her responsibility to transfer no more than the least amount of information that her company owed us, and she valiantly proved her worth in that endeavor.

She was much better made up one day after that picture was taken, but there were no photos taken that day. heh heh

These guys worked for Polly. They tried not to tell us anything beyond

the legal requirement, but you could tell their hearts weren't in it.

These guys worked for Polly. They tried not to tell us anything beyond

the legal requirement, but you could tell their hearts weren't in it.

Transfer of intellectual property by traditional means wasn't going well at

all. So we tried some less formal methods. That didn't work any better,

but it was entertaining.

Transfer of intellectual property by traditional means wasn't going well at

all. So we tried some less formal methods. That didn't work any better,

but it was entertaining.

English food is bland, but Indian food most definitely is not. Not having a

magic bus, we usually took a taxi to

English food is bland, but Indian food most definitely is not. Not having a

magic bus, we usually took a taxi to

Manchester's Rusholme neighborhood.

There, dozens of restaurants specialize in curried dishes from the Asian

sub-continent.

Manchester's Rusholme neighborhood.

There, dozens of restaurants specialize in curried dishes from the Asian

sub-continent.

Didsbury is another neighborhood in Manchester where we spent a few evenings.

It was a little closer to the factory than Rusholme, and had better variety of

restaurants.

The Saints and Scholars have wrens guarding their fence, at left in the

first photo.

The Dog and Partridge.

The jug is just left of the front door.

We ate at Café Rouge a few times. They had excellent crème

brûlée. Occasionally, they had street entertainment, too.

Pubs are for lunch, and for killing time while we waited for supper time. The

English take their evening meal much later than we do.

Pubs are for lunch, and for killing time while we waited for supper time. The

English take their evening meal much later than we do.

This is the Hare and Hounds, not far from the factory we were visiting, in

Hale Barns.

These ladies are having a chat at the Goose, in central Manchester. Like

London, Manchester has a place called Piccadilly.

These ladies are having a chat at the Goose, in central Manchester. Like

London, Manchester has a place called Piccadilly.

We often had lunch at the Romper, which was the closest pub to the factory we

were visiting.

The United Kingdom includes four countries. From Manchester, we were in easy driving range of three: England (of course), Scotland, and Wales. So Barbara and I drove to Scotland and Wales, just so we could say we had visited. Even if it was only long enough for a snapshot.

Scotland

The bridge is in Powfoot. The garden is on the left side of the road.

The bridge is in Powfoot. The garden is on the left side of the road.

The bridge isn't very wide. Apparently, not everybody clears it.

Wales

Their language sounds as odd as it looks.

A gold cape found at Mold is one of the most valued exhibits in the British Museum. Almost four thousand years old, it was beaten from a single gold ingot. It was used to dress a body for burial.

"St. Mary's Church in a Hollow of White Hazel Near the Rapid Whirlpool

of St. Tysilio's Church by the Red Cave."

The village got its unusual name sometime in the late 19th century.

Residents, probably after a few pints, thought that if their town had the

longest name in the world, it might entice folks to get off the train and see

what's there. I didn't see a whirlpool, or a red cave.

The village got its unusual name sometime in the late 19th century.

Residents, probably after a few pints, thought that if their town had the

longest name in the world, it might entice folks to get off the train and see

what's there. I didn't see a whirlpool, or a red cave.

There are at least two disputes to the "longest name" claim: one in New Zealand (85 letters) and one in Thailand (168 letters). But Llanfair PG is the one everyone remembers.

The clock tower is a memorial to the soldiers and sailors who didn't come

home from World War I (Y Rhyfel Mawr, The Great War).

Holyhead

The place is at land's end, on an island at the end of an island at the

northwest end of Wales. Lord John Stanley owned the

Penrhos estate here.

His son William, a noted antiquarian, excavated some ancient dwellings on the

estate's Tŷ Mawr (Great House) Farm. Some of them were as old as the Mold

Cape. The farm is still in operation, but its 16th-century main house is now

an upscale B & B.

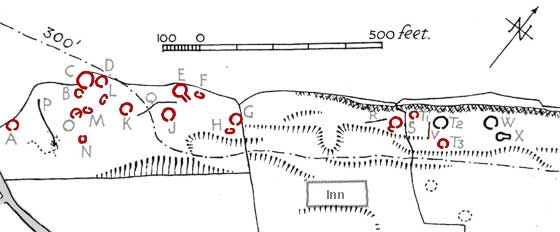

There was a small settlement on the farm, a group of stone huts originally dated from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age (c. 2000 BC). Mr. Stanley found over fifty structures, of which only twenty remained for a 1937 inventory of ancient monuments in northern Wales. Seventeen have been preserved for today's visitor; three at the northeast end are either unexcavated or overgrown.

– after An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Anglesey, HM Stationery Office, London, 1937.

I wish I had known more about the history and layout of this place before visiting. It would have made the difference between interesting and fascinating. I also would have chosen my photos better. Most of them are from a small group of huts at the southwest end of the preserved group. To make the story complete, I've added drawings and photos from two old sources that I didn't know about before this visit. The woodcuts are from Stanley's 1871 memoir. The black-and-white photos are from the 1937 RCAHMW report on ancient monuments.

In local literature and on British Ordnance Survey maps, the settlement is called Cytiau'r Gwyddelod, or Irishmen's Huts. No Irishmen ever lived here; the term might have been a pejorative reference for primitive people. Modern excavations (1978–82) showed that the ages of the buildings range over more than 1000 years, from about 800 BC to 200 AD. The older Neolithic and Bronze Age estimates were based on finding flint arrowheads at the site.

The buildings used partly-buried stone walls, with a system of wood poles supporting a conical thatched or turf roof. The larger round houses were primarily residential. Based on the metal slag found in excavations, the smaller, oblong buildings were workshops.

The settlement was mainly agricultural. Finds of grinding stones point to processing grain. Discarded sea shells, especially limpets (snails), indicate another important food source, easily obtained nearby.

William Stanley conducted two excavations here, in 1862 and 1868. The first

one unearthed Hut J, one of the more accessible structures. This is the

same hut in the artist's rendering above, but the artist viewed it from the

side away from the entrance. The hut had two large stones at the entrance,

which are still there. The entrance was three feet across, widening to

six feet before it opened into a main room about 18 feet across. There were

knee-high partitions, grinding stones for milling grain, and three

fireplaces.

William Stanley conducted two excavations here, in 1862 and 1868. The first

one unearthed Hut J, one of the more accessible structures. This is the

same hut in the artist's rendering above, but the artist viewed it from the

side away from the entrance. The hut had two large stones at the entrance,

which are still there. The entrance was three feet across, widening to

six feet before it opened into a main room about 18 feet across. There were

knee-high partitions, grinding stones for milling grain, and three

fireplaces.

Substantial caches of seashells were found in this hut, and there were several smooth round stones that had obviously been heated strongly. This led Stanley to conclude that Hut J was used for cooking. He worked out that the people cooked meat by simmering it in the animal's skin. The skin would be filled with water and the round rocks heated intensely. Then the rocks were transferred to the water, heating it and the meat in it.

All of the other huts I saw were unearthed in Stanley's second dig, in 1868.

The first one the visitor sees is Hut A, near the road and some farm

buildings.

The prevailing wind here blows from the Northwest.

Like the rest of the village, this hut was built to open on the southeast

side.

There was a hearth on one side with a fireplace at either side; and a large

fireplace in the middle of the room.

All of the other huts I saw were unearthed in Stanley's second dig, in 1868.

The first one the visitor sees is Hut A, near the road and some farm

buildings.

The prevailing wind here blows from the Northwest.

Like the rest of the village, this hut was built to open on the southeast

side.

There was a hearth on one side with a fireplace at either side; and a large

fireplace in the middle of the room.

This building (Hut "O" on the drawing) is unique because of the interior wall.

There may have been an annex on the right side of the first view.

This building (Hut "O" on the drawing) is unique because of the interior wall.

There may have been an annex on the right side of the first view.

Hut M is adjacent. It's easy to see the T-shaped channel that was once

here. This, plus the type of pots and amount of slag here, indicate that it

was probably a metalworking shop.

Hut M is adjacent. It's easy to see the T-shaped channel that was once

here. This, plus the type of pots and amount of slag here, indicate that it

was probably a metalworking shop.

Hut B.

Neither Stanley nor the government report has much to say about this one,

except for dimensions. It's about half the size of the other roundhouses

nearby.

The residence Hut C had several clues to daily life in the village. It is

unique for the little ante-room at the entrance, which had its own fireplace

and a stone mortar set into a crude platform. This fireplace used a chimney;

the ones inside the hut did not. For those fireplaces, smoke filtered

through the roof to the outside.

Inside the hut, Stanley found a lot of

slag and several Roman coins from the second century AD. It is

not clear if the Romans used these huts, or if the villagers melted the coins

to make tools and weapons. There was a deep quern (grinding stone) inside.

Diggers also found a large collection of limpet and periwinkle shells here.

The residence Hut C had several clues to daily life in the village. It is

unique for the little ante-room at the entrance, which had its own fireplace

and a stone mortar set into a crude platform. This fireplace used a chimney;

the ones inside the hut did not. For those fireplaces, smoke filtered

through the roof to the outside.

Inside the hut, Stanley found a lot of

slag and several Roman coins from the second century AD. It is

not clear if the Romans used these huts, or if the villagers melted the coins

to make tools and weapons. There was a deep quern (grinding stone) inside.

Diggers also found a large collection of limpet and periwinkle shells here.

Hut D completes the roundhouse cluster near the southwest end of the village.

It flanks Hut C on the other side from Hut B. A

fireplace remains in its center, and rubbing stones are installed in the

floor.

Hut D completes the roundhouse cluster near the southwest end of the village.

It flanks Hut C on the other side from Hut B. A

fireplace remains in its center, and rubbing stones are installed in the

floor.

Hut L is another workshop-sized building in the southwest group. Its walls

are unusual, made of large single stones (orthostats) rather than dry-walled.

This is an accidental opening at one end, not the

normal entrance which is hidden on the right side. There is a small stone

seat at the opposite end, not visible in this picture.

Hut L is another workshop-sized building in the southwest group. Its walls

are unusual, made of large single stones (orthostats) rather than dry-walled.

This is an accidental opening at one end, not the

normal entrance which is hidden on the right side. There is a small stone

seat at the opposite end, not visible in this picture.

Hut K is set off from the others a bit, but not so much as the cooking-hut

"J". This one has survived the ages very well. With a new set of poles and

a roof, the original residents would probably feel right at home.

Hut K is set off from the others a bit, but not so much as the cooking-hut

"J". This one has survived the ages very well. With a new set of poles and

a roof, the original residents would probably feel right at home.

This hut (E) is unique. It's partly built into the hillside, and it has a very well-protected entrance — a hallway longer than the hut's diameter. The second drawing shows how the artist imagined the built-in fireplace might have looked, along with the mortar and rubbing stone set into the floor. Several stones were found here that had greenish marks consistent with sharpening metal weapons of copper or bronze.

There is a smaller workshop-style hut (F) next to Hut E that also looks to

be especially secure. It has a slightly longer entrance than the other small

huts, and the walls are also taller than average.

There is a smaller workshop-style hut (F) next to Hut E that also looks to

be especially secure. It has a slightly longer entrance than the other small

huts, and the walls are also taller than average.

Like the others, Hut G has a good view of Tŷ Mawr Farm and the Irish Sea.

It's just out of the scene to the left, but the hut was pared a bit

when a relatively modern farmer built a boundary wall. This is shown on the

plan above as well as the satellite shot here.

Like the others, Hut G has a good view of Tŷ Mawr Farm and the Irish Sea.

It's just out of the scene to the left, but the hut was pared a bit

when a relatively modern farmer built a boundary wall. This is shown on the

plan above as well as the satellite shot here.

Turning away from the sea, the visitor can walk about

500 feet to the rest of the village,

with a view of Holyhead Mountain half a mile

ahead. Nobody knows why the last few huts are separated from the main

group. Maybe it was a suburb.

Turning away from the sea, the visitor can walk about

500 feet to the rest of the village,

with a view of Holyhead Mountain half a mile

ahead. Nobody knows why the last few huts are separated from the main

group. Maybe it was a suburb.

Hut S was the first one Stanley excavated on his 1868 dig. It

doesn't look like much, but he got a lot of information from it. This hut

taught him about the inside division of the hut, and that it was partly paved

("flagged"). Like Hut C, it had a small annex with a pounding stone and

quern. As in Hut M, copper slag was found here. This too was a

toolmaker's home.

Hut S was the first one Stanley excavated on his 1868 dig. It

doesn't look like much, but he got a lot of information from it. This hut

taught him about the inside division of the hut, and that it was partly paved

("flagged"). Like Hut C, it had a small annex with a pounding stone and

quern. As in Hut M, copper slag was found here. This too was a

toolmaker's home.

The 1937 plot plan shows four ancient walls, labelled P Q R and V. Wall V seems to be part of the excavated works at the northeast end, but the other three are not visible.

Although I came here to see the work of prehistoric man, the natural beauty of this place

is a strong draw. The hut village was once part of Tŷ Mawr Farm, still

operating after several hundred years. Hut M is barely visible in the

foreground of the first photo.

Although I came here to see the work of prehistoric man, the natural beauty of this place

is a strong draw. The hut village was once part of Tŷ Mawr Farm, still

operating after several hundred years. Hut M is barely visible in the

foreground of the first photo.

There is also a fine inn about a hundred feet

east of the site, which commands the same view. Visibility is good here.

The smokestack on the horizon at left is on a factory about

eight miles away.

It's not all rocks and archaeology. Along with the view, today's visitor can enjoy the same flora as the people who built here four thousand years ago — mountain heath, ferns, and dwarf gorse.

There is more information about the Tŷ Mawr hut circles on the Anglesey Island Information site and at the UK Stone Circles site.

England

Hadrian's Wall marks the end of the Roman Empire. Two centuries after Julius

came and conquered what he saw

(veni, vidi, vici), Hadrian realized that

the Picts were no pushovers, and decided it was better to simply wall them

out. Or wall the Romans in. Either way, he built a strong defensive barrier

from today's Newcastle to Dumfries, roughly along the border between modern

England and Scotland.

Hadrian's Wall marks the end of the Roman Empire. Two centuries after Julius

came and conquered what he saw

(veni, vidi, vici), Hadrian realized that

the Picts were no pushovers, and decided it was better to simply wall them

out. Or wall the Romans in. Either way, he built a strong defensive barrier

from today's Newcastle to Dumfries, roughly along the border between modern

England and Scotland.

Most of the wall was built of stone, with milecastles (garrisons) at regular

intervals. Turrets, or guardhouses, were built between the milecastles. The

wall took six years to build. most of the labor being furnished by Roman

legionnaires. These were not slaves; they were volunteers who joined the

army because they were eligible for citizenship when their enlistment was

done.

Most of the wall was built of stone, with milecastles (garrisons) at regular

intervals. Turrets, or guardhouses, were built between the milecastles. The

wall took six years to build. most of the labor being furnished by Roman

legionnaires. These were not slaves; they were volunteers who joined the

army because they were eligible for citizenship when their enlistment was

done.

The engineers and guards were mostly local recruits called auxiliaries (helpers).

The military zone extended from a deep ditch on the north side of the wall to a ditch flanked by earth mounds, the Vallum, running along the south of the wall. In due course a road now known as the Military Way was built south of the wall to improve communications along its length.

We saw the Willowford wall, turrets, and bridge, part of Hadrian's Wall just west of Gilsland. Some economy is apparent here (photo above). The foundation is the standard 3-meter width, but the wall is the narrow variant, two meters wide.

As they built the wall, the soldiers left inscriptions to note their military

division, home town, and such. Signs at the site interpret these mementoes,

but I don't know how the anthropologists got anything intelligible out of

these markings. As they say, that's why they get paid the big bucks.

As they built the wall, the soldiers left inscriptions to note their military

division, home town, and such. Signs at the site interpret these mementoes,

but I don't know how the anthropologists got anything intelligible out of

these markings. As they say, that's why they get paid the big bucks.

This is the base of Turret 48B, which was excavated in 1923. The soldiers

who worked here had a fairly ordinary existence. Like guards everywhere

before the video age, they probably got to be pretty good at board games.

Today's guards are mostly sheep and cattle.

The golden fleece tells us these are not ordinary animals. They're Cotswold

sheep, whose wool is prized almost as highly as the merino. There is some

evidence that they were brought to this part of the world in Hadrian's time,

but that evidence is thin. If you'd like to read the whole story, it's on

the web site of the

Cotswold Woollen Weavers.

On the way from Hadrian's Wall to our next stop, we found this bench on the

Low Row near Greenhead (about seven miles east of Brampton).

Here is the view it commands, looking northwest.

Castlerigg

There are stone circles all over the British Isles and northwestern France. Some are more sophisticated than others, but all of them share a striking astronomical accuracy. We visited Castlerigg Stone Circle in the Lake District. It looks a lot more primitive than Stonehenge (we'll get to that!), but it's actually a bit newer. As usual, the signs on the site tell the story best. With some modification, …

The present approach to Castlerigg Stone Circle seems to follow the original

entrance route. The circle has been owned since 1913 by the National Trust.

It was one of the first dozen sites to be declared an ancient monument in 1883

and the stones are in the guardianship of English heritage.

It isn't known who built Castlerigg, but there are clues. The builders would have come from the early farming communities who probably lived on the fringes of the mountainous region, from which they obtained the raw material for their tools.

The Stone Circles in Britain seem to have been built between 2500–1300 BC during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Two stone axes and a stone club found near the circle in the 18th century AD suggest a Neolithic (New Stone Age) construction.

The builders would have found the stones lying in the immediate area. All are of Borrowdale volcanic stone, brought by glaciers from rocky outcrops during the last Ice Age.

The Circle is not a true circle, but flattened on the eastern side. The stones would have been dragged to the site on log rollers and then levered into prepared holes, which were then packed with soil and stones. The unique rectangular "sanctuary" may be contemporary with the main circle.

The building of the Circle would have required similar planning and effort to the construction of a church in medieval times.

Castlerigg would have been important to every member of the local tribal community. Isolated groups would have been able to come here to barter livestock, exchange partners or celebrate tribal festivals. There is evidence that the Circle was also a means of calculating the cycle of the seasons, something that would have been crucial to early farmers to whom the sun would have been a vital factor for survival, especially in Cumbria.

A couple of miles south of Castlerigg, we spent some time at Lake Thirlmere.

Blackpool, a few minutes after a thunderstorm.

Blackpool, a few minutes after a thunderstorm.

Lytham St. Anne's is not far away. Obviously, this picture was not taken on

the same day as the one at Blackpool.

on to Lancaster

Manchester

Powfoot

Mold

Llanfair PG

Holyheaad

Willowford

Castlerigg

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Woodhenge

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

References

Home