Home

Manchester

Powfoot

Mold

Llanfair PG

Holyheaad

Willowford

Castlerigg

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Woodhenge

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

to the story's beginning back to York

Chester

Chester

Chester has the most complete circuit of Roman, Saxon, and medieval city walls in Britain. It's possible to walk almost completely around the original city on top of the walls even today, and the layout within them hasn't changed much in the last five or six hundred years.

The city is certainly old, as Barfoot and Wilkes assert in the 1792 Chester Directory: "The ancient name of this city was Neomagus, so called from Magus, son of Samothes, son of Japet, himself a son of Noah …"

As for the documented history of the city, we can use the information from the

sign that is part of a series to be found all along the walls.

As for the documented history of the city, we can use the information from the

sign that is part of a series to be found all along the walls.

The Romans called the city Deva, after the Celtic name for the then-great river that dominated the place, Dyfrdwy (now the River Dee).

AD 70s: the Romans build wooden defenses. The legionary fortress of Deva was the main base for the Roman army in North Wales and Northwest England. An area shaped like a playing card was enclosed by a turf rampart and protected by wooden palisade towers and gateways.

AD 100: Stone walling was added to the front of the earth rampart. The towers and gateways were rebuilt in stone. These strong stone defenses survived long after the collapse of the Roman Empire in about 400 AD.

907: The Mercian princess Ęthelflęda created a burgh or fortified town as a defense against Viking raids. The Saxons re-used the old Roman walls and perhaps extended earth banks down to the river.

1120–1350: the circuit is completed. Chester's Norman earls repaired and restored the existing walls and built the southern and eastern sides facing the river. In the Middle Ages, tall projecting towers and impressive gateways were added.

1642–46: Civil War. The Royalists built extensive earth banks to protect the suburbs. The walls and towers were battered and breached by cannon fire, until the city was starved into surrender.

18th century: Once the walls had outlived their military usefulness, they were converted to a fashionable promenade around the city. The gateways were replaced by elegant arches. Many of the towers were pulled down or altered.

We began our visit to Chester at the Northgate. Here are some views from the

Bridge of Sighs there, including a look at the canal that had to be built when

silting changed the River Dee's course, robbing the great Port of Chester of

its harbor.

We began our visit to Chester at the Northgate. Here are some views from the

Bridge of Sighs there, including a look at the canal that had to be built when

silting changed the River Dee's course, robbing the great Port of Chester of

its harbor.

This raised platform is named after a Civil War gun emplacement just outside the city wall. The name commemorates Captain Morgan, a Royalist officer who is said to have commanded the battery there. Chester was loyal to King Charles I during the Civil War of 1642-46. The city was besieged for eighteen months by Parliamentarian forces. Their guns bombarded the defenses, causing great damage to the walls, before the city was forced to surrender.

On 4 October 1645, a large cannon in Morgan's Mount was destroyed by Parliamentarian gunfire.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the walls were repaired and strengthened. An extensive system of ramparts with gun mounts was built to defend the suburbs outside the city walls. As the Civil War progressed and the siege tightened, Chester's outworks were reduced in length as the Royalists abandoned the suburbs and retreated inside the city walls.

When the canal was being dug along here, workers found human skulls and bones from the Civil War.

The Queen's School for Girls (1883).

This is the northwest corner of the medieval wall. Two towers were built at

different times to protect the harbor when Chester was a busy port. In the

12th and 13th Centuries, the River Dee flowed right up to the walls at this

point. The tower called Bonewaldesthorne's Tower stood at the water's edge,

guarding the ships moored below the city wall.

Silt continued to choke the river channel and within 100 years, the Water Tower was left standing on dry land.

By the early 14th century, silting had caused the river to change course away from the walls. So the New Tower was built standing out in the river, connected to the defenses by a spur wall. Ships tied up at large.

Soon the river was so shallow that large ships could no longer reach Chester. In the 1730s eight miles of the Dee were canalized to ease the navigation. A new harbor was built at Crane Wharf over 650 feet beyond the Water Tower. Some shipping continued well into the 19th century.

The Water Tower and Spur Wall were built in 1322-33 by John de Helpestron, a stone mason. It cost £100. Masons were paid 3d a day and laborers 2d. Women who carried the stones received 1d.

The course of the river has changed a lot since the days when Chester was a major port. Then, it came right up to the city wall. Silting of the River Dee led to the decline of the port. A new harbor was built downstream in the 1730s. Trade continued until the late 19th century, but today the Port of Chester survives in name only.

Chester's main trade was with Ireland, but ships also brought goods from all over Europe: wines from France and Spain, furs from Scandinavia, Flemish cloth, spices from the Far East and armor from Italy.

Tolls were charged on all goods. "The Keeper of the Watergate takes...of every ship or boat coming to the gate with large fish or salt salmon, one fish with herring, fifty…"

The Sergeants of the Watergate were the Stanley family, Earls of Derby. Their fine Tudor mansion, Stanley Palace, is 100 yards away in Watergate Street.

The port has long gone, but the Mayor of Chester still bears the title Admiral of the Dee.

I couldn't photograph the Watergate because we were standing right on top of

it, but here's the Inn.

I couldn't photograph the Watergate because we were standing right on top of

it, but here's the Inn.

No apologies to Richard Nixon.

Chester Castle lies within the medieval city wall. Originally built by William the Conqueror in 1070 to guard the Welsh border, it later became the Royal base for the military conquest of North Wales. The first Norman castle was a timber tower built on an earth mound. Below was the bailey, a defended enclosure containing the living accommodation. During the 12th and 13th Centuries, the castle was rebuilt in stone.

Hugh Lupus, the first Earl of Chester, held his Parliament at the Castle between 1077 and 1101. You can still visit the surviving medieval parts of the Castle, including a 12th-century gate tower called Agricola Tower. By the late 18th century, the medieval castle was in very poor repair. Between 1788 and 1822 the lower ward was completely rebuilt in neo-classical style by the architect Thomas Harrison.

Thomas Harrison also designed the Grosvenor Bridge nearby. Opened in 1833, this was the largest single span stone bridge in the world at that time.

Stanley Palace, formerly called Derby House, stands on or near the site

previously occupied by the Dominican Friars (the 'Black Friars') in medieval

times. It was built in 1591 for Sir Peter Warburton, a Chester lawyer and MP

for the City, then passed as his daughter's dowry to the Stanleys of Alderley.

Stanley Palace, formerly called Derby House, stands on or near the site

previously occupied by the Dominican Friars (the 'Black Friars') in medieval

times. It was built in 1591 for Sir Peter Warburton, a Chester lawyer and MP

for the City, then passed as his daughter's dowry to the Stanleys of Alderley.

In 1889 it was bought by the Earls of Derby. It was restored and presented to the City Corporation in 1929.

James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby, was an outspoken Royalist, even after the Civil War. In 1651, he was executed for treason after a brief house arrest. His ghost is said to wander around the ground-floor rooms of Stanley Palace. Curiously, it always appears as a photographic negative.

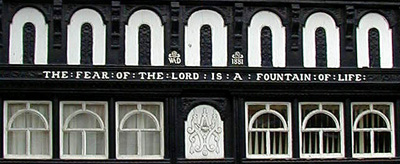

These Tudor houses, with their scripture, are all over the city.

These Tudor houses, with their scripture, are all over the city.

The wishing steps were built in 1785 to join two levels of the Walls as part of the creation a walkway on which to promenade. Tradition has it that anyone who makes a wish at the foot of the steps and then runs up and down them without taking a breath will have their wish come true. One version of the tale suggests this is a particular "facility" for young maidens aspiring to wedlock.

In his 1924 work, In Search of England, author H.V. Morton recalled, "Why? I asked a man who was standing on them, looking as though none of his wishes had ever come true. 'Well', he said, in the curiously blunt way they have here, 'You have to run up and down and up again without taking breath, and then they say you'll get your wish.'"

This house is nearby, just inside the wall.

The bandstand on The Groves was built in 1913, at a cost of £350.

From time to time, excavations in Chester turned up relics from Roman times.

They have been assembled in the Roman Garden, just outside the southeast part

of the wall.

From time to time, excavations in Chester turned up relics from Roman times.

They have been assembled in the Roman Garden, just outside the southeast part

of the wall.

These are pieces of Roman columns.

This boy is playing on a reconstructed hypocaust, an early heating system.

The floor is raised on pillars (pilæ). The building would have

been designed so that hot air and smoke from a nearby furnace pass below the

floor and into a flue across the room. This heats the floor, and the room,

without filling it with smoke and odors.

This boy is playing on a reconstructed hypocaust, an early heating system.

The floor is raised on pillars (pilæ). The building would have

been designed so that hot air and smoke from a nearby furnace pass below the

floor and into a flue across the room. This heats the floor, and the room,

without filling it with smoke and odors.

There were several places on the wall where we saw Off The Wall, a restaurant.

They probably didn't have to try too hard to find a name for the place.

There were several places on the wall where we saw Off The Wall, a restaurant.

They probably didn't have to try too hard to find a name for the place.

Outside and off the wall. This is the Newgate, completed in 1938. It is on

the site of the former Wolfgate, where the Roman wall met the Saxon extension.

By the 1930s it was plain that the Wolfgate was too narrow to accommodate

automobile traffic, and the city fathers wanted to remove it. Rather than

leave a gap in the wall (a major historical artifact), they built the Newgate

next to Wolfgate. Despite appearances, its construction is reinforced

concrete. The red sandstone is a veneer.

Outside and off the wall. This is the Newgate, completed in 1938. It is on

the site of the former Wolfgate, where the Roman wall met the Saxon extension.

By the 1930s it was plain that the Wolfgate was too narrow to accommodate

automobile traffic, and the city fathers wanted to remove it. Rather than

leave a gap in the wall (a major historical artifact), they built the Newgate

next to Wolfgate. Despite appearances, its construction is reinforced

concrete. The red sandstone is a veneer.

Turning around from this position, the photographer sees the Roman

amphitheatre.

Turning around from this position, the photographer sees the Roman

amphitheatre.

Amphitheatres were a distinctive feature of the western provinces of the Roman Empire and even today their remains are striking monuments of Roman skill in architecture and engineering.

Amphitheatres were used to provide brutal entertainment — combat to the death between armed gladiators, or the slaughter of wild animals in mock hunts — but another important purpose was their use as weapon training establishments. For this purpose the arena would be used to demonstrate a particular exercise, and then as a practice ground by the soldiers. A particularly interesting feature at Chester is the small room immediately west of the north entrance. This served as a shrine of the goddess Nemesis and contained a stone altar dedicated to her. A modern copy has been placed on the site of the original which is now in the Grosvenor Museum.

A fortress as big and important as Deva would certainly have had an amphitheatre, but until the 20th century nobody knew where it was, or even if it had existed. In June 1929, while examining a pit dug on the convent grounds to remove a large tree, the gardener discovered large pieces of stone. He thought they were the foundation of some building, but his boss, W.J. Williams, realized that they had to be relics of the amphitheatre. Shortly after this discovery, a workman found a coin from Hadrian's realm. Exploratory trenches confirmed what this site really was.

It's ironic that the amphitheatre was almost lost. Part of the planning to

modernize traffic around the old Wolfgate would have had a new road running

directly across this site. A lot of planning had already been done, and

Chester city fathers did not want it disturbed by digging for an old stadium.

The controversy simmered until 1933, when the national Ministry of Works

refused to allocate money for the original plan. This saved the site from

destruction, but money was still needed for excavation.

It's ironic that the amphitheatre was almost lost. Part of the planning to

modernize traffic around the old Wolfgate would have had a new road running

directly across this site. A lot of planning had already been done, and

Chester city fathers did not want it disturbed by digging for an old stadium.

The controversy simmered until 1933, when the national Ministry of Works

refused to allocate money for the original plan. This saved the site from

destruction, but money was still needed for excavation.

The County Council had occupied St. John's House, which sat on the site. They finally moved out and the house was demolished in 1958. Excavation finally began in 1960. The site was not opened to the public until 1972, 43 years after its discovery.

These are the ruins of the original east end of St. John's Church. They

include part of the Norman chancel, the 14th-century Lady Chapel, and two

medieval side chapels. St. John's was Chester's first cathedral. In 1075,

Bishop Peter Litchfield moved the seat of his diocese to Chester and began to

build a cathedral church on the site of Æthelred's original Saxon church. It

is not known why he chose to build outside the city walls in such turbulent

times. In 1102 the See was moved to Coventry, but St. John's remained an

important collegiate church.

These are the ruins of the original east end of St. John's Church. They

include part of the Norman chancel, the 14th-century Lady Chapel, and two

medieval side chapels. St. John's was Chester's first cathedral. In 1075,

Bishop Peter Litchfield moved the seat of his diocese to Chester and began to

build a cathedral church on the site of Æthelred's original Saxon church. It

is not known why he chose to build outside the city walls in such turbulent

times. In 1102 the See was moved to Coventry, but St. John's remained an

important collegiate church.

The church took over 100 years to build, reaching its most complete form in

the late 13th century. It was then more than twice the length of the church

today. In the 14th century it was further extended to the east, when three

semi-circular Norman apses were replaced by the chapels which are now ruined.

The church took over 100 years to build, reaching its most complete form in

the late 13th century. It was then more than twice the length of the church

today. In the 14th century it was further extended to the east, when three

semi-circular Norman apses were replaced by the chapels which are now ruined.

After the Dissolution St. John's became a parish church. The eastern chapels and the transepts were abandoned. Unable to maintain such a large building, the parishioners built a new east wall, leaving the ruined east end outside the church.

There are many stories about the coffin embedded in the wall here. This

account is from the

Chester Walls web site.

The Chester Guides, a race not yet quite extinct, have made up many foolish stories about this solid oak coffin for the delectation of their Lancashire dupes, who usually pay more court to that ghastly old shell than to the beautiful architectural ruins and church that adjoin it.

One story is that it was the coffin of a monk who murdered one of his brethren at St. John's, and at his own death was refused the ordinary Christian burial, whether within the church or beneath the green sod of the churchyard.

Another is that a dignitary of the church was at his own request 'buried' up there in a standing position, so that, when the last trumpet should sound, he might be ready at once to answer the call.

Another is that a wicked old parishioner of past days was unable to rest in his grave, and that Satan himself had helped to place him in the lofty position so that he might look down, in perpetual penance, on the fair world he had defiled by his sins. I have overheard during the last dozen years every one of these stories recounted in sober earnest by Mr. Guide to his morbid listeners.

The real story of the coffin is soon told. Forty years ago, when a boy at school, I remember old John Carter, the sexton of the Cathedral, going with me at my request into St. John's Ruins (at that time enveloped within a brick wall, and portion of the of the old Priory House), to show me the relic and then fresh-looking inscription. He assured me on the spot that his father, who was sexton of St. John's a great number of years, had in his younger days come upon the coffin while digging a grave in a long disused part of the churchyard; and had, by the Rector's orders, stuck it up in the recess where it still stands, so that it might be out of the way of passers by!

Thus has a very matter of fact in incident given rise in superstitious minds to no end of mystery. The date of the coffin is probably of the latter half of the 15th century and the relic has this one element of real interest in it, that it is composed of a single block of oak which has been hollowed out to receive the body".

The sexton's father may have merely "stuck the coffin up in the recess", but the photograph would seem to indicate that some forgotten mason went to considerable trouble to ensure that it stayed there.

Next to the ruins along the River Dee is Grosvenor Park, whose twenty acres

were given to the city in 1867 by Richard, the second Marquis of Westminster.

The park was designed by Edward Kemp, a famous landscape architect of the

time. It is regarded as one of the finest and most complete examples of

Victorian parks in England, if not the world. Many changes have taken place

since the beginning, but most of Kemp's original designs and features remain.

Next to the ruins along the River Dee is Grosvenor Park, whose twenty acres

were given to the city in 1867 by Richard, the second Marquis of Westminster.

The park was designed by Edward Kemp, a famous landscape architect of the

time. It is regarded as one of the finest and most complete examples of

Victorian parks in England, if not the world. Many changes have taken place

since the beginning, but most of Kemp's original designs and features remain.

The Lodge was originally the Park Keeper's Lodge, and is still used as the

city's Parks and Gardens Office. Here's Barbara getting a closer look at some

of the statues on the Lodge. The statues represent important people in the

city's history, beginning with William the Conqueror.

The Lodge was originally the Park Keeper's Lodge, and is still used as the

city's Parks and Gardens Office. Here's Barbara getting a closer look at some

of the statues on the Lodge. The statues represent important people in the

city's history, beginning with William the Conqueror.

People from New York are called New Yorkers. In Britain, it's more complicated. The residents of cities are called by names that often derive from the city's name in Latin or another older language. Some are only nicknames.

| Birmingham | Brummie |

| Cambridge | Cantabrigian |

| Glasgow | Glaswegian |

| Manchester | Mancunian |

| Newcastle | Geordie |

| Oxford | Oxonian |

| Shropshire | Salopian |

People from Chester are Cestrians, whether shopping for antiques or

looking for relief.

People from Chester are Cestrians, whether shopping for antiques or

looking for relief.

People from Liverpool are Liverpudlians. That term is a joke, but most people never get it: a puddle is a small pool.

In The Cross, old Chester's main intersection, the town crier makes his

announcements at noon. At other times, shown here, anybody can speak.

Between this fellow's preachings, a heckler was trying to out-shout him.

In The Cross, old Chester's main intersection, the town crier makes his

announcements at noon. At other times, shown here, anybody can speak.

Between this fellow's preachings, a heckler was trying to out-shout him.

A mini-roundabout at the edge of the pedestrian zone. The English use

roundabouts in many places where we use traffic lights. Trucks can't make the

tight turn around the center of a mini-roundabout, but cars are expected to

respect it.

A mini-roundabout at the edge of the pedestrian zone. The English use

roundabouts in many places where we use traffic lights. Trucks can't make the

tight turn around the center of a mini-roundabout, but cars are expected to

respect it.

St. Peter's Church is at the end of the street, at The Cross.

The Rows. a covered shopping district, may have been built on the rubble of a

fire that devastated Chester in 1278. The first mention of the Rows in

written history is shortly after that date.

Chester Cathedral.

The stone is in the Chester Guards Memorial Garden, seen in the center photo.

King Charles Tower, or the Phoenix Tower

This is the northeastern corner of Chester's Roman and medieval defenses. A Roman angle tower stood near the site of this medieval watch tower.

When Chester was the Roman fortress of Deva, the large field inside the walls was the site of the legionary barrack blocks. These were long narrow buildings, each housing a century of 80 men with separate quarters for the commanding officer or centurion.

5000 to 6000 highly trained soldiers, living in over sixty barrack blocks within the fortress. The legion most closely associated with Chester was Legio XX Valeria Victrix — the Brave and Victorious Twentieth Legion.

Some 700 years after the Romans left Chester, this section of wall was rebuilt with strong defensive towers. This tower, originally called Newton's or Phoenix Tower, was badly damaged during the Civil War (1642–46) and had to be largely rebuilt.

On 24 September 1643, King Charles I stood on this tower and saw the scattered remnants of his army fleeing from defeat at the Battle of Rowton Moor, about two miles southeast of Chester. The King moved to the Cathedral Tower, where he was almost hit by a bullet fired by a Parliamentarian sniper.

There is a Phoenix carved above the upper door. This was the emblem of the Painters' and Surgeons' Guilds, who used this tower as a meeting place until the 17th century.

The Eastgate clock is the second-most photographed clock in Britain (there's

another famous clock in London that gets more attention). For many it is the

symbol of the ancient city of Chester, although it is only a little over 100

years old. It was built to celebrate the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria's

rule in 1897.

The Eastgate clock is the second-most photographed clock in Britain (there's

another famous clock in London that gets more attention). For many it is the

symbol of the ancient city of Chester, although it is only a little over 100

years old. It was built to celebrate the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria's

rule in 1897.

Virtus non Stemma

Virtus non Stemma

Virtue, not pedigree (is the mark of nobility).

Here are two views of Eastgate Street, looking toward the clock and down away

from it.

on to Bath

Manchester

Powfoot

Mold

Llanfair PG

Holyheaad

Willowford

Castlerigg

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Woodhenge

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

References

Home