Home

Manchester

Powfoot

Mold

Llanfair PG

Holyheaad

Willowford

Castlerigg

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Woodhenge

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

to the story's beginning back to Llanfair P.G.

Bath

Although the cathedral looks — and is — normal, the visitor

quickly sees that Bath is not an ordinary city. This begins with the Roman

columns on the bridgehouse. Something is out of place. Roman architecture on

a modern bridge?

The architecture is Roman, but the mood of the city is Georgian. Most of it

is due to one man,

Richard "Beau" Nash (1674–1761). He was not merely a

dandy; he was the original Chic Police. Nash studied Law at Oxford, but was

dismissed for womanizing. He tried the Army but that didn't suit him

either. Then he realized he was skilled at gambling.

The architecture is Roman, but the mood of the city is Georgian. Most of it

is due to one man,

Richard "Beau" Nash (1674–1761). He was not merely a

dandy; he was the original Chic Police. Nash studied Law at Oxford, but was

dismissed for womanizing. He tried the Army but that didn't suit him

either. Then he realized he was skilled at gambling.

Bored with London, Nash decided to try his luck in Bath, which was gaining

popularity as a health spa. He was soon appointed Master of Ceremonies.

This happened after the former M.C. was killed in a duel, so Nash banned the

wearing of swords. Then he built an Assembly House and collected a fee for

it from all Bath visitors. He banned private parties, but invited visitors

to the Assembly for meals, breakfast concerts, and balls — which ran

promptly from six to eleven PM. Behavior and dress at these events were

strictly prescribed by the Master of Ceremonies.

Bored with London, Nash decided to try his luck in Bath, which was gaining

popularity as a health spa. He was soon appointed Master of Ceremonies.

This happened after the former M.C. was killed in a duel, so Nash banned the

wearing of swords. Then he built an Assembly House and collected a fee for

it from all Bath visitors. He banned private parties, but invited visitors

to the Assembly for meals, breakfast concerts, and balls — which ran

promptly from six to eleven PM. Behavior and dress at these events were

strictly prescribed by the Master of Ceremonies.

Nash was busiest from 1720 to the 1740s. In this period he engaged the architect John Wood the Elder, who designed the buildings that have drawn tourists to Bath for nearly three hundred years. Thus began Bath's reign as a center for artists, writers, and high society in general. Today the city is a magnet to a very flamboyant population.

Nash was so well known as a fashion plate that Lord Chesterfield famously said,

He wore his gold-laced clothes on the occasion, and looked so fine that, standing by chance in the middle of the dancers, he was taken by many at a distance for a gilt garland.

- Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield

Bath had laws against gambling, but Nash got around them by inventing new games. As Master of Ceremonies, he received a percentage of the proceeds. In 1745 the anti-gambling law was strengthened, and Nash's personal fortune began to decline. By the time he died, he was a man of very modest means. But his name was forever linked to the city he built around a humble hot spring. Beau Nash is buried in the nave of Bath Abbey, the city's cathedral.

According to legend, Bath was founded by King Bladud in the Ninth century BC.

Bladud Son of Ludhudibras

Eighth King of the Britans,

from Brute. A Great Philosopher

& Mathematician, Bred at

Athens & Recorded the first

Discoverer, and Founder of

These Baths, Eight Hundred

Sixty Three Years Before

Christ, that is Two Thousand

Five Hundred Sixty Two Years

to the Present Year 1690

Bladud's father, King Ludhudibras, sent him to Athens to be educated in the

liberal arts. When his father died, he returned to England with four

philosophers to claim his throne. He also founded a university at Stamford,

Lincolnshire.

Bladud's father, King Ludhudibras, sent him to Athens to be educated in the

liberal arts. When his father died, he returned to England with four

philosophers to claim his throne. He also founded a university at Stamford,

Lincolnshire.

But while he was in Athens, he had contracted leprosy, and his people imprisoned him. He escaped, and found work herding pigs. He noticed that some of the pigs would wander off, and return covered in warm, thick, black mud. He also noticed that these pigs did not have skin diseases like the other pigs, who wallowed in ordinary mud.

So he tried the mud bath himself, and was cured of his leprosy. He founded the City of Bath on the site of the warm springs, dedicating a temple there to the goddess Minerva, also called Athena or Sulis.

He was restored to his royal position in 863 BC, and ruled for twenty years before dying in unusual circumstances.

Bladud practiced necromancy, a kind of channelling through the spirits of the dead. In this way, he learned how to fly. He built a set of wings for himself and flew from the Temple of Apollo in New Troy (now London). But he hit a wall and broke his neck.

He was succeeded by his son, King Lear.

Well, that's how the story goes.

The facilities at Bath generally followed the Roman model.

The universal acceptance of bathing as a central event in daily life belongs to the Roman world and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that at the height of the empire, the baths embodied the ideal Roman way of urban life. Apart from their normal hygienic functions, they provided facilities for sports and recreation. Their public nature created the proper environment—much like a city club or community center—for social intercourse varying from neighborhood gossip to business discussions. There was even a cultural and intellectual side to the baths since the truly grand establishments, the thermæ, incorporated libraries, lecture halls, colonnades, and promenades and assumed a character like the Greek gymnasium.

– Fikret Yegül, Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity, MIT, Cambridge, 1992, pg. 30

The Roman day was ruled by the Sun. Work began at sunrise and was usually done by noon. In the afternoon, men would go to the baths for a few hours of exercise, conversation, and relaxation before heading home to dinner. Some bathhouses had separate facilities for men and women; others segregated by time, with women using the bath in the morning while the men were working.

Bathers usually exercised before taking the plunge. This might include wrestling, weight-lifting, ball games, running, and swimming in a cold-water pool. Some women exercised, but this was mostly a masculine activity.

After exercise, bathers scraped down with a curved tool called a strigil. Then they would partake of progressively warmer baths until they reached one that was so hot they periodically needed to splash some cool water on. A quick dip in the cold pool finished the ritual.

After bathing, patrons could stroll in the garden, visit the library, or take in some entertainment such as jugglers, acrobats, or musicians.

There is a scale model to inform the visitor how the baths were most likely

laid out. It was probably at ground level in Roman times, but the Great Bath

is about one story below street level today.

There is a scale model to inform the visitor how the baths were most likely

laid out. It was probably at ground level in Roman times, but the Great Bath

is about one story below street level today.

On our way into the baths, we passed through the Pump Room, a tea room whose

trappings are carefully researched to reflect its late-18th-century heyday.

This attention to detail extends to the clothing worn by the staff and the

type of music performed (violin trio).

On our way into the baths, we passed through the Pump Room, a tea room whose

trappings are carefully researched to reflect its late-18th-century heyday.

This attention to detail extends to the clothing worn by the staff and the

type of music performed (violin trio).

We took advantage of the chance to drink some spa water. It's at the natural temperature (116°F), and is said to contain 43 minerals. Nobody told us what those minerals are.

This is the King's Bath,

built around the Sacred Spring. King Bladud, whom we met earlier, presides

from an alcove to the right of the central arch.

This is the King's Bath,

built around the Sacred Spring. King Bladud, whom we met earlier, presides

from an alcove to the right of the central arch.

The spring produces 240,000 gallons of 116-degree water each day, feeding all of the baths here as well as that fountain in the Pump Room. The source is about 10,000 feet below the Earth's surface.

This is the King's Bath, The Romans built the stone chamber around the spring

and lined it with lead. They also built the plumbing system that routes water

from the spring to all the other baths in the complex.

This is the King's Bath, The Romans built the stone chamber around the spring

and lined it with lead. They also built the plumbing system that routes water

from the spring to all the other baths in the complex.

Originally, the spring room was covered by a vaulted roof, but the roof collapsed in the sixth or seventh century.

The Romans believed that the spring was the work of the goddess Minerva, and

threw offerings to her into it.

The Romans believed that the spring was the work of the goddess Minerva, and

threw offerings to her into it.

Some of the offerings were rolls of lead or pewter with prayers inscribed on them. Some of the prayers were curses.

As in a modern locker room, there was plenty of opportunity for theft in the Roman baths. Bathers' slaves watched their clothes and valuables while they were in the water. There were storage nooks, but they probably didn't have doors or locks.

It was hot in the bath house, which required an effort for the watchers to stay awake. Too, some of them were not immune from bribery. So it sometimes happened that bathers left the bath with some of their belongings missing. There were no police to call, so the Roman victim implored the gods, usually Minerva, to punish the thief. First they "gave" the missing items to Minerva, then asked her to impose some dire punishment on the thief for having offended her. Usually, the requested punishment was far out of proportion to the crime.

The concept has not been lost completely. There are still people in the modern world who use voodoo dolls.

Sometimes the curses were written backwards, which was thought to imbue the magic with extra potency.

Over one hundred curses have been recovered from the Spring by excavation.

Docimedis has lost two gloves. He asks that the person who has stolen them should lose his mind and his eyes in the temple where she appoints.

Curses were folded or rolled before they were thrown into the Spring.

To Minerva the goddess Sulis I have given the thief who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether slave or free, whether man or woman. He is not to buy back this gift unless of his own blood.

Curses were inscribed on sheets of pewter or lead.

I curse him who has stolen, who has robbed Docimedis from his house. Whoever stole his property the god is to find him. Let him buy it back with his blood and his own life.

The names of those suspected of crimes were sometimes listed on a curse.

May he who has stolen VII from me become as liquid as water …

The Great Bath is just over five feet deep, an ideal depth for bathing. Steps

lead into it from all sides.

The Great Bath is just over five feet deep, an ideal depth for bathing. Steps

lead into it from all sides.

It is lined with 45 sheets of lead.

The people next to Julius Cæsar aren't using cell phones. Those are

audio guides.

The people next to Julius Cæsar aren't using cell phones. Those are

audio guides.

Originally, the Great Bath was covered by a massive vaulted roof. This

terrace and its statues date to the 1890s.

Originally, the Great Bath was covered by a massive vaulted roof. This

terrace and its statues date to the 1890s.

The hypocaust, or central heating system, of the East Bath. Hot air was

forced below the floor, which was raised on stone pillars

(pilæ).

The first-century

Temple of Minerva at Bath stood six feet up on a podium.

Worshippers entered a windowless room to pray to a statue of the goddess, lit

only by a fire in front of it.

The first-century

Temple of Minerva at Bath stood six feet up on a podium.

Worshippers entered a windowless room to pray to a statue of the goddess, lit

only by a fire in front of it.

When the Sacred Spring was enclosed a century later, side chapels were added. The temple was a religious center through the fourth century, when the Roman Empire embraced Christianity. In AD 391, the emperor Theodosius ordered all pagan temples closed, and the Temple of Minerva eventually collapsed. Some of the carved stones were repurposed as pavers. Their excavation has helped to assemble the story of early religion in Roman Britain.

Today, the temple has been restored as a museum. The great ornamental pediment survived, and has been reassembled here. The head is thought to be that of a Gorgon, a powerful symbol of the goddess Sulis Minerva.

Tombstone of Calpurnius Receptus, a priest of Sulis Minerva, in the form of an

altar.

Tombstone of Calpurnius Receptus, a priest of Sulis Minerva, in the form of an

altar.

D(is) M(anibus) G(aius) Calpurnius (R)eceptus sacerdos deae Sulis vix(it) an(nos) LXXV Calpurnia Tritosa L[i]bert(a) coniunx F(aciendum) C(uravit)

To the spirits of the departed, Gaius Calpurnius Receptus, priest of the goddess Sulis, lived 75 years; Calpurnia Tritosa, his freedwoman (and) wife, had this set up.

The stone shows reversed letters and spelling corrections (sacerdos, third line).

D M MERC... MAGNI L ALUMNA VIXIT AN I M VI D XII

To the spirits of the departed and Merc[urius] the foster child of Lucius Magnus, who lived one year, six months, and twelve days.

Stone tablet showing the goddess Minerva.

Stone tablet showing the goddess Minerva.

A Gorgon's head mask is fixed across her stomach.

Found 1882.

Deae Suli

L Marcius Memor

Harusp(ex)

D(ono) Dedit

To the goddess Sulis Lucius Marcius Memor, Haruspex, gave [this as] a gift

This stone probably stood next to a statue of the goddess Sulis, which had been commissioned by the priest Lucius Marcius Memor.

A haruspex was a priest with the special power to advise on the meaning of omens such as the flight of birds, and might interpret the internal organs of sacrificed animals. He might be consulted before an important event to see if it was an auspicious moment, but warnings were not always heeded.

The o in Memor looks like it was an afterthought. More likely, it was a correction to a botched engraving. Literacy rates were very low in Roman times.

The original Roman plumbing system is still largely in place. Lead pipes

carry water around the spa using gravity flow.

The original Roman plumbing system is still largely in place. Lead pipes

carry water around the spa using gravity flow.

The hot spring's 240,000 gallons per day are more than enough to keep the baths full. The surplus passes through this overflow into the Roman Great Drain, which carries it 400 yards to the River Avon.

The cold plunge bath is unusually large. It was used for an invigorating dip

after treatments in the hot rooms and baths. Like the Great Bath, it is five

feet deep.

The cold plunge bath is unusually large. It was used for an invigorating dip

after treatments in the hot rooms and baths. Like the Great Bath, it is five

feet deep.

These days, it looks like it's used as a wishing well.

This tapestry, 1000 Years of English Monarchy, hangs in the great hall

near the Pump Room. It is an embroidered panel by

Audrey Walker, commissioned

by the City of Bath in 1973, on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the

coronation of Edgar, first King of All England.

The tapestry is quite large (about 8 × 6 feet), and poorly

sited for photography. The image is scanned from a souvenir postcard.

This tapestry, 1000 Years of English Monarchy, hangs in the great hall

near the Pump Room. It is an embroidered panel by

Audrey Walker, commissioned

by the City of Bath in 1973, on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the

coronation of Edgar, first King of All England.

The tapestry is quite large (about 8 × 6 feet), and poorly

sited for photography. The image is scanned from a souvenir postcard.

Edgar's coronation took place in the Saxon chapel on the location of Bath Abbey,

which can be seen from several places in the baths.

Edgar's coronation took place in the Saxon chapel on the location of Bath Abbey,

which can be seen from several places in the baths.

I couldn't get to a good place to photograph all of Bath Abbey at once. There

has been an important church on this site for over a thousand years, but it

has gone through several re-buildings.

I couldn't get to a good place to photograph all of Bath Abbey at once. There

has been an important church on this site for over a thousand years, but it

has gone through several re-buildings.

The first Abbey was built here in 675. Originally a convent, then a monastery, it was rebuilt as a church in the 8th century. It was in that church that Edgar was crowned the first King of All England.

The abbey was re-built as a Norman cathedral in the 12th century, but later bishops preferred to run their affairs from Wells. So the cathedral fell out of use, and was in ruins by the late 15th century.

Work began on a new cathedral in 1500; it was finished about thirty years later.

The story continues, but first a look inside…

The story continues, but first a look inside…

This stone is in the main aisle.

The East End window shows 56 scenes from the life of Jesus. The guide tells a

story of a shard of glass from this window, shattered by a bomb in World War

II, that travelled all the way to Canada in the pocket of an airman who was in

Bath at the time of the blast.

In 1539 King Henry VIII broke away from the Church of Rome and ordered the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The cathedral was stripped of lead, iron and glass, and left to rot for a generation.

From 1574 to 1611 Queen Elizabeth I promoted another restoration, so this could serve as the grand parish church of Bath.

James Montague, Bishop of Bath during this time, paid £1000 toward that

restoration, making him one of the Bath Abbey's most generous benefactors.

James Montague, Bishop of Bath during this time, paid £1000 toward that

restoration, making him one of the Bath Abbey's most generous benefactors.

This is his alabaster tomb on the North Aisle.

During the 1860s there was more major reconstruction. At that time the timber

roof was replaced with the intricate fan vaulting seen here.

During the 1860s there was more major reconstruction. At that time the timber

roof was replaced with the intricate fan vaulting seen here.

The stained glass is exquisite, and there are hundreds of ornate tombs.

Woodhenge

Woodhenge was unknown until Gilbert S.M. Insall flew over it shortly before Christmas 1925. Two miles from Stonehenge, he recognized a pattern in the farm land below. Farmers had long known that wheat grew thicker on certain parts of the land. They associated this with old burial mounds that had been plowed over. But no pattern was visible from the ground. Insall flew over it again as the crop matured, taking this photo the following summer. The patterns of thicker growth were plain to see from overhead, but not at all on the ground.

Insall showed his photos to Maud and Ben Cunnington, who excavated the land,

then bought it a few years later. Woodhenge is the oval pattern just above

and left of center, near a farmstead in the 1926 photo that is not there

today. The smaller rings below and right of center are not in evidence in

modern times, either from the air or the ground. They are barrows that have

been plowed flat without revealing anything of archæological importance.

Insall showed his photos to Maud and Ben Cunnington, who excavated the land,

then bought it a few years later. Woodhenge is the oval pattern just above

and left of center, near a farmstead in the 1926 photo that is not there

today. The smaller rings below and right of center are not in evidence in

modern times, either from the air or the ground. They are barrows that have

been plowed flat without revealing anything of archæological importance.

Unlike at Stonehenge, there was no central altar, but there was a stone in the

middle of the structure that had obviously been used for human sacrifice. The

Cunningtons recovered the bones of a three-year-old child whose head had been

split open with an ax. The remains were taken to London, where they were

destroyed during World War II — a casualty of Blitzkrieg.

Unlike at Stonehenge, there was no central altar, but there was a stone in the

middle of the structure that had obviously been used for human sacrifice. The

Cunningtons recovered the bones of a three-year-old child whose head had been

split open with an ax. The remains were taken to London, where they were

destroyed during World War II — a casualty of Blitzkrieg.

Rather than try to reconstruct the original structure, the Cunningtons placed

168 color-coded concrete posts at the locations of the disturbances Insall

photographed. There are six oval rings. The longer axis is aligned with the

midsummer sunrise in one direction and the midwinter sunset in the other.

A ditch surrounding the rings is broken by a causeway to accommodate an

entrance from the Northeast.

Rather than try to reconstruct the original structure, the Cunningtons placed

168 color-coded concrete posts at the locations of the disturbances Insall

photographed. There are six oval rings. The longer axis is aligned with the

midsummer sunrise in one direction and the midwinter sunset in the other.

A ditch surrounding the rings is broken by a causeway to accommodate an

entrance from the Northeast.

The second photo shows one of a pair of bronze plaques placed in 1929 as a visitors' guide. Sadly, these plaques were stolen in November 2015.

Carbon dating put the site at 2300 BC, older than some parts of

Stonehenge. But newer techniques used in the 1970s suggest that the

structure was in use as late as 1800 BC.

Carbon dating put the site at 2300 BC, older than some parts of

Stonehenge. But newer techniques used in the 1970s suggest that the

structure was in use as late as 1800 BC.

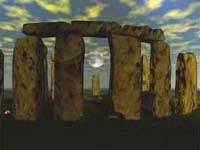

Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a monument to the gulf between what we observe and what we

understand. Who built this thing, and why? Ample evidence of human sacrifice

demonstrates that this was a place of religious observance. Simple

observation marks it as a very accurate astronomical register. The builders

probably didn't see much difference between the two realms. The Sun's motion

is deeply linked to planting and harvest, and if we botch those activities we

starve.

Stonehenge is a monument to the gulf between what we observe and what we

understand. Who built this thing, and why? Ample evidence of human sacrifice

demonstrates that this was a place of religious observance. Simple

observation marks it as a very accurate astronomical register. The builders

probably didn't see much difference between the two realms. The Sun's motion

is deeply linked to planting and harvest, and if we botch those activities we

starve.

The place was built gradually over two thousand years, a time frame that boggles the modern mind. We are impressed by relatively modern cathedrals in Europe that took a few hundred years to complete, but this is a short time in comparison. It's very possible that the purpose of the monument changed dramatically from its beginning to its completion.

For a long time, people simply saw an interesting pile of rocks.

(This is the view in 1877, before modern reconstruction efforts began.)

Then the 18th-century antiquarian William Stukely happened to notice the

particular alignment of the Sun as it rose on the morning of summer solstice.

This led him to believe that Stonehenge was a Druid temple. That was

reinforced by the knowledge of other contemporary religious structures like

the pyramids of Egypt, and later buildings in ancient

Greece and Rome. There are over 400 burial mounds, indicating that

powerful people thought it was important to begin their journey into the

afterlife here.

For a long time, people simply saw an interesting pile of rocks.

(This is the view in 1877, before modern reconstruction efforts began.)

Then the 18th-century antiquarian William Stukely happened to notice the

particular alignment of the Sun as it rose on the morning of summer solstice.

This led him to believe that Stonehenge was a Druid temple. That was

reinforced by the knowledge of other contemporary religious structures like

the pyramids of Egypt, and later buildings in ancient

Greece and Rome. There are over 400 burial mounds, indicating that

powerful people thought it was important to begin their journey into the

afterlife here.

In the 20th century, the astronomical features were emphasized, adding to the idea that this was a scientific place as well as religious. It seems that it's not difficult to impart any meaning one would like, and there's ample material to support most theories.

The name of the place is a hybrid. It has stones, and it has a henge. It's most familiar to the modern observer because of the stones, but the surrounding earthwork is what supplied the name. What is a henge? It's certainly not an everyday word. As explained by noted archæologist Mike Pitts,

Technically, they are earthwork enclosures in which a ditch was dug to make a bank, which was thrown up on the outside edge of the ditch. To the military-minded, this immediately excludes any practical, defensive function for the ditches and banks. …

Henges can be very small or very large, sometimes with more than one enclosing bank or ditch, and with one or more "entrances" or breaks in the circuit. They frequently have standing stones somewhere in or around them. When excavated, they are often seen to have had large erect posts in or outside the enclosed space. But most of all, every henge is unique. These may have been sacred places, but they were not built to a common blueprint like medieval churches. And it is one of the strangest things that while we know of hundreds of these enclosures in Britain, few if any have yet been found elsewhere in Europe.

– Mike Pitts, Hengeworld, Century, London, 2000, pg. 28.

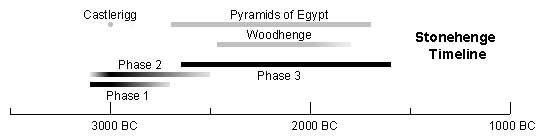

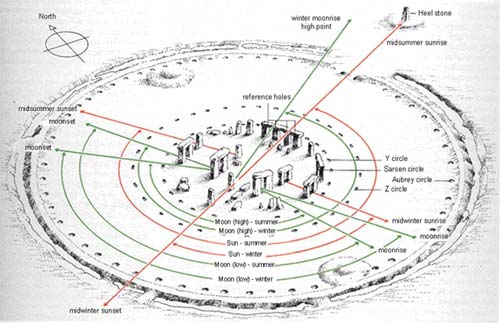

How Stonehenge was BuiltStonehenge as we see it now is the final stage that was finished about 3500 years ago, but the site was active at least 1500 years before then. Archæologists separate the development into three phases.

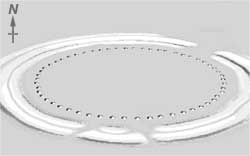

Phase 1. The earthwork, or henge.

Phase 1. The earthwork, or henge.

The earliest stage comprises a large henge —

a ditch about six feet deep, between two banks

that were made from the excavated material. Animal bones have been found in

the ditch, but these may have been simply worn-out digging tools. The main

entrance is from the Northeast, aligned with sunrise on the summer solstice.

There was also a secondary entrance from the South, which is not apparent

today.

Inside the earthwork are 56 pits forming a circle about 284 feet across. These are named for the antiquarian John Aubrey, who discovered them in 1666. Modern astronomers Gerald Hawkins and Fred Hoyle believed it was possible to predict eclipses by moving three markers individually around these holes according to a schedule. When all three markers arrived at the same hole, either the Sun or the Moon was about to be eclipsed. Wooden poles were in the Aubrey Holes at first, but we can only guess at their purpose.

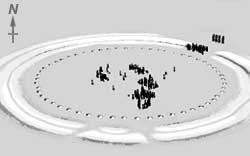

Phase 2: Wooden poles.

Phase 2: Wooden poles.

It isn't entirely clear what was going on in Phase 2, but there were

several wooden posts on the site. They don't appear to have any special

pattern except for some in the northeast causeway that would have served as

astronomical markers. The illustration shows a confusing pattern because it

represents all of the wooden posts from this phase. They were

probably not all there at the same time, so there might be patterns that we

can't pick out.

The posts were removed from the Aubrey Holes, which began to be used for burying cremated remains. There were also cremation burials in the surrounding ditch.

Beginning about 4500 years ago, the stones began to arrive. Although he was better known as an Egyptologist, Flinders Petrie conducted the first accurate survey of Stonehenge in the late 19th century. He devised a numbering system to identify the stones, including some that are missing or buried. That plan is available several places on the internet. Simon Banton uses it on his web site The Stones of Stonehenge, a catalogue of photographs of each individual stone. Any stone numbers here are from Petrie's system.

Phase 3: Bluestones.

The term bluestone is used to describe any "foreign" rock at

Stonehenge; that is, rock that isn't local. Most of it is igneous Dolerite,

brought here beginning about 2500 BC from the Preseli Mountains in

southwestern Wales. The stones were moved on rollers to rafts, where they

were floated up the River Avon and finally dragged to the center of the site,

where they were first set up in the pattern seen here.

The Altar Stone was placed at the west end of the horseshoe, with double

bluestones most of the way around. At the other end of the horseshoe, stones

were triples and quads about the main axis of the site.

The Altar Stone was placed at the west end of the horseshoe, with double

bluestones most of the way around. At the other end of the horseshoe, stones

were triples and quads about the main axis of the site.

The Sarsen Heelstone (#96) and a partner (#97) were placed in this phase. At the summer solstice, the Sun rose between these two stones as viewed from the Altar Stone. Sometime later, Stone 97 was removed, leaving only the Heelstone.

Construction began on The Avenue, a path illuminated by the midsummer sunrise, and the four Station Stones were set in a rectangle whose long sides marked the extreme positions of moonrise and moonset.

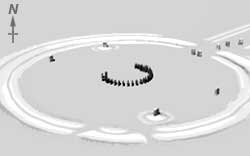

Phase 3b. Sarsen stones.

Phase 3b. Sarsen stones.

The name is a Wiltshire derivative of Saracen, which was used locally

to mean anything not Christian. The rock is a hard, dense sandstone bound by

a silica cement. These large stones were only moved about 25 miles or less,

almost certainly by dragging them on sleds. They were arranged in an outer

circle with a continuous run of lintels. Five trilithons (two posts and a

lintel) were arranged as a horseshoe inside the circle. This all happened

about 2000 BC, or four thousand years ago.

The sarsens of the outer circle and inner trilithons are fitted with techniques usually seen in woodworking, not masonry. The builders used toungue-and groove, and mortise-and-tenon joints, which undoubtedly helped to maintain the integrity of the structure.

Phase 3c and later.

The bluestones are not shown on the diagram above to reduce clutter. They

were rearranged in stages: first as a double horseshoe to mirror that of the

sarsens, later as a pair of rings. Finally, stones were removed from the

inner bluestone ring to leave a horseshoe inside the sarsen trilithons.

The bluestones are not shown on the diagram above to reduce clutter. They

were rearranged in stages: first as a double horseshoe to mirror that of the

sarsens, later as a pair of rings. Finally, stones were removed from the

inner bluestone ring to leave a horseshoe inside the sarsen trilithons.

About 1100 BC, The Avenue was extended another mile and a half to the Avon River. Two more rings of holes were dug outside the sarsen circle, in line with the stones already there. Some experts speculate that these may have been intended to place more stones, but that development never happened. After that, the record is silent for two thousand years, until Henry of Huntingdon mentions it in his Historia Anglorum (History of the English People (1129)):

Stanenges, where stones of wonderful size have been erected after the manner of doorway, so that doorway appears to have been raised upon doorway; and no one can conceive how such great stones have been raised aloft, or why they were built there.

The diagram below shows the final position of the stones that remain, with red lines pointing out the rising and setting Sun at the solstices. The Aubrey holes were near the outer circle formed by the original earthworks.

summer

winter

- winter sunset photo © Simon Banton

The satellite photo shows the Avenue very clearly, entering from upper right.

It also shows where visitors must walk, on the left side. After too many

years of disturbances, especially at the solstices, English Heritage has

restricted access to the site. We could get close, but not inside the stone

circle.

Private-access tours inside the circle are available, but must be

booked months in advance.

The satellite photo shows the Avenue very clearly, entering from upper right.

It also shows where visitors must walk, on the left side. After too many

years of disturbances, especially at the solstices, English Heritage has

restricted access to the site. We could get close, but not inside the stone

circle.

Private-access tours inside the circle are available, but must be

booked months in advance.

Here's what we could see from the public-access path, staring at the northwest walkway and proceeding counter-clockwise around the stones. The path let us get reasonably close on the west side, but kept us outside the earthworks for most of the circuit. This path can be seen on the satellite photo above.

This is the view from the Southeast, on the line of the sunrise at winter

solstice. The trilithon at the center is lined up with the one behind it.

The Eastern Station Stone (SS91) is at the right of the scene, just beyond the

earthworks of Phase 1.

This is the view from the Southeast, on the line of the sunrise at winter

solstice. The trilithon at the center is lined up with the one behind it.

The Eastern Station Stone (SS91) is at the right of the scene, just beyond the

earthworks of Phase 1.

Two views of the Heelstone, also called the Friar's Heel or Sun Stone. The

second view is looking directly northeast, toward the midsummer sunrise. As

the Sun rises, it also moves southward. From the Altar Stone inside the

circle, the viewer would see the Sun break the horizon next to the Heelstone

if it weren't obscured by distant hills. In the ten minutes it takes the Sun

to rise above the Heelstone, it has moved over so it's directly aligned there.

Two views of the Heelstone, also called the Friar's Heel or Sun Stone. The

second view is looking directly northeast, toward the midsummer sunrise. As

the Sun rises, it also moves southward. From the Altar Stone inside the

circle, the viewer would see the Sun break the horizon next to the Heelstone

if it weren't obscured by distant hills. In the ten minutes it takes the Sun

to rise above the Heelstone, it has moved over so it's directly aligned there.

Burial mounds, as seen by satellite and by humans.

The stone circle and parking lot are in the lower half of the satellite view.

Burial mounds, as seen by satellite and by humans.

The stone circle and parking lot are in the lower half of the satellite view.

There were four "station stones" arranged in a 5:12 rectangle outside the

sarsen circle, but within the surrounding earthworks. Their purpose is not

known, but we do know that

There were four "station stones" arranged in a 5:12 rectangle outside the

sarsen circle, but within the surrounding earthworks. Their purpose is not

known, but we do know that

- the short sides are parallel to the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset

- the long sides are aligned to the southernmost moonrise and the northernmost moonset

Two of the stones are missing. They were on the North and South Barrows that can be seen in one of the drawings above. This is one of the two survivors, simply called the Western Station Stone. An observer on the North Barrow will see the midwinter Sun set over this stone.

John Constable, 1835

on to London

Manchester

Powfoot

Mold

Llanfair PG

Holyheaad

Willowford

Castlerigg

Blackpool

Lancaster

York

Chester

Bath

Woodhenge

Stonehenge

London

Rochester

Canterbury

Dover

References

Home