It's been nine years since we

visited Atlantic Canada. Where does the time

go? Some of the people we visited in 2003 are gone now; some new ones have

arrived.

Again, we flew, but even the old flying club is no

longer there. We rented a Cherokee Arrow,

N9478N, from the new flying service. Life is full of trade-offs. N9478N

isn't as fast as the Mooney we used in 2003, and it holds less fuel. Both of

these things limit our non-stop distance, especially IFR. But this plane can carry almost 150

pounds more than the Mooney, which opened up a couple of other possibilities

for us.

It's been nine years since we

visited Atlantic Canada. Where does the time

go? Some of the people we visited in 2003 are gone now; some new ones have

arrived.

Again, we flew, but even the old flying club is no

longer there. We rented a Cherokee Arrow,

N9478N, from the new flying service. Life is full of trade-offs. N9478N

isn't as fast as the Mooney we used in 2003, and it holds less fuel. Both of

these things limit our non-stop distance, especially IFR. But this plane can carry almost 150

pounds more than the Mooney, which opened up a couple of other possibilities

for us.

As we did on our convention trip two years

ago, we took along Barbara's grandchildren Josh and Jessie. They're two

years older now (14 and 12), and a little bigger than they were in 2010.

So N9478N's extra payload came in handy. The kids have been flying with us

since they were each a year old, so they're old pros. But this was their

first trip out of the U.S. We all had some things to see and learn.

As we did on our convention trip two years

ago, we took along Barbara's grandchildren Josh and Jessie. They're two

years older now (14 and 12), and a little bigger than they were in 2010.

So N9478N's extra payload came in handy. The kids have been flying with us

since they were each a year old, so they're old pros. But this was their

first trip out of the U.S. We all had some things to see and learn.

This is mainly a story about our trip, and what we saw and did on the ground. There is plenty of material on the internet about flying in general, and about U.S. pilots flying to Canada in particular. I've decided to include some notes anyway. These might be interesting to pilots, but will be boring to everybody else. To help the general reader skip these notes, they're set off in little boxes like this paragraph.

We visited these airports and places:

We visited these airports and places:

Moncton, New Brunswick - Customs, overnight

Glace Bay, Nova Scotia - overnight

Digby, Nova Scotia - overnight

Halifax, Nova Scotia - overnight

Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia - side trip

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia - side trip

Bangor, Maine - fuel and Customs

Milford, Conn. - home

In the past, we've had excellent luck with the weather on our

flying vacations. The Maritime Provinces are nothing if not unpredictable.

So we didn't get off easy this time around. As we passed Hartford,

Conn., on our first leg, we knew we were seeing the last of good weather

for a few days.

In the past, we've had excellent luck with the weather on our

flying vacations. The Maritime Provinces are nothing if not unpredictable.

So we didn't get off easy this time around. As we passed Hartford,

Conn., on our first leg, we knew we were seeing the last of good weather

for a few days.

We stopped for fuel in Lewiston, Maine, where Lufthansa is

restoring a Lockheed Constellation to flying status. They keep this one

handy for spare parts. I would not want to have the bill for this project.

We stopped for fuel in Lewiston, Maine, where Lufthansa is

restoring a Lockheed Constellation to flying status. They keep this one

handy for spare parts. I would not want to have the bill for this project.

Then it was on to an instrument approach at Moncton, New Brunswick, where the

kids got an introduction to the metric system.

They also got a charge out of spotting familiar stores with specialized

Canadian signs. They coined a new word and started looking for things that

had been "leafatized."

They also got a charge out of spotting familiar stores with specialized

Canadian signs. They coined a new word and started looking for things that

had been "leafatized."

Moncton is home to

Magnetic Hill, an optical illusion that has spawned an

amusement center

– including a zoo and a water park. There is a white stick about halfway

along the piece of road in this picture, at a place that looks like a

low point between two shallow hills. We were instructed to drive to this

point, stop the car and take it out of gear. Sure enough, the car rolled

backwards!

Moncton is home to

Magnetic Hill, an optical illusion that has spawned an

amusement center

– including a zoo and a water park. There is a white stick about halfway

along the piece of road in this picture, at a place that looks like a

low point between two shallow hills. We were instructed to drive to this

point, stop the car and take it out of gear. Sure enough, the car rolled

backwards!

Two things contribute to the illusion. The horizon must be obscured, so the observer doesn't have a good reference for which way the road really slopes. The trees along the side of this road, and the steeper slope that begins near the white stick, take care of that. The steeper slope after the white stick gives the further illusion that the stick is at the bottom of two shallow hills. So, while all of the road in the photo is uphill, the viewer has the visual cues of driving first down one hill, then up another.

We were in the area to see the famous tides of the Bay of Fundy, the highest

in the world. At Hopewell Rocks, the tide rises through 43 feet when the moon

is full. The rock formations give a graphic measurement of the tidal flow,

drawing visitors from all over the world. The tides are higher in Nova

Scotia's Minas Basin, but the bay floor slopes gradually there, so the visual

effect is not so dramatic.

We were in the area to see the famous tides of the Bay of Fundy, the highest

in the world. At Hopewell Rocks, the tide rises through 43 feet when the moon

is full. The rock formations give a graphic measurement of the tidal flow,

drawing visitors from all over the world. The tides are higher in Nova

Scotia's Minas Basin, but the bay floor slopes gradually there, so the visual

effect is not so dramatic.

When we saw Cape Blomidon nine years ago, we walked over half a mile from the high-tide line to water's edge on mud flats that were uncovered at low tide.

Like all enclosed bodies of water, the Bay of Fundy is a resonant system, with its most responsive frequency determined by the shape of its shoreline and bottom. Because the most responsive frequency of the Bay matches the daily tide cycle so well, the response is enormous - in the same way that every child knows the best time to push a friend on a swing.

We started our physics lesson at Hopewell Cape, one of the best places to see the stark contrast between high and low tides.

The road from Moncton to Hopewell Cape passes the

New Brunswick Railway Museum

in Hillsborough. The museum staff like to tell the story of how they

acquired this CF-101 Voodoo fighter, complete with hair-raising tales of its

landing in the museum's parking lot.

The road from Moncton to Hopewell Cape passes the

New Brunswick Railway Museum

in Hillsborough. The museum staff like to tell the story of how they

acquired this CF-101 Voodoo fighter, complete with hair-raising tales of its

landing in the museum's parking lot.

This Voodoo, #101028, was among the "second batch" purchased from McDonnell Aircraft in 1970-72 ("first batch" were built in 1961). The second batch served Canada as front-line interceptors through 1984.

It was raining lightly when we headed for

Hopewell Rocks Provincial Park. But the experts were forecasting better

weather to come, so we got on our way. In the Maritimes, lupines bloom in

June. There were still a few near their peak, waiting to welcome us to the

park. Although the leaves are a little reminiscent of marijuana, you can't

smoke lupines.

It was raining lightly when we headed for

Hopewell Rocks Provincial Park. But the experts were forecasting better

weather to come, so we got on our way. In the Maritimes, lupines bloom in

June. There were still a few near their peak, waiting to welcome us to the

park. Although the leaves are a little reminiscent of marijuana, you can't

smoke lupines.

The park's trail to the Hopewell Rocks looks like the maid was just here. At

the end of the trail, there's a staircase from an overlook down to the bottom

of the Bay of Fundy.

This is the place most folks think of when you mention Hopewell Rocks, seen at

the tidal extremes. A couple of days later, the moon was full. High

tide would then rise to a level that would not let those kayakers paddle

beneath the arch.

This is the place most folks think of when you mention Hopewell Rocks, seen at

the tidal extremes. A couple of days later, the moon was full. High

tide would then rise to a level that would not let those kayakers paddle

beneath the arch.

Many of the rocks have names. It's easy to see why this one is called

Lovers' Arch. The smaller rock between the arch and the cliff is called the

Bear because of its shape. Do you see its ears?

Many of the rocks have names. It's easy to see why this one is called

Lovers' Arch. The smaller rock between the arch and the cliff is called the

Bear because of its shape. Do you see its ears?

The first picture (left) shows Angle Rock. The one in the third picture is

named for E.T.

This one resembles Abe Lincoln, a foreigner in New Brunswick. I don't know

if it even has a name.

Here is Diamond Rock at low tide, and again at high tide.

We wandered around on the bottom of the Bay of Fundy for a couple of hours,

looking for fossils and taking in the view. This scene is from Castle Cove.

Nearby, Jessie inspected a cave or two, …

… and anointed her new sneakers. It's a good thing there was

a wash station handy.

… and anointed her new sneakers. It's a good thing there was

a wash station handy.

By the time we finished our low-tide exploration, the sky had begun to clear

a bit. When we first passed this point, we could not see that shoreline

around the bend.

By the time we finished our low-tide exploration, the sky had begun to clear

a bit. When we first passed this point, we could not see that shoreline

around the bend.

Here we see Daniels Flats, a large mud flat named for an early settler in

this area. The clouds obscure two significant geographical features; but

they have interesting stories, so I'll tell them anyway. The base of

Shepody Mountain is just visible on the right, about three miles away. The

top of this hill is often shrouded in clouds. When Samuel de Champlain saw

this place in 1604-05, he noted in the ship's log that it looked like the Hat

of God, or chapeau de dieu. Over time, this name morphed into

Shepody. Eight miles straight ahead lies Grindstone Island, but today

it's only there in our imagination.

We're in Albert County, which is rich in granite.

Large numbers of grindstones were produced on this island. The mines are

gone but the name remains.

Here we see Daniels Flats, a large mud flat named for an early settler in

this area. The clouds obscure two significant geographical features; but

they have interesting stories, so I'll tell them anyway. The base of

Shepody Mountain is just visible on the right, about three miles away. The

top of this hill is often shrouded in clouds. When Samuel de Champlain saw

this place in 1604-05, he noted in the ship's log that it looked like the Hat

of God, or chapeau de dieu. Over time, this name morphed into

Shepody. Eight miles straight ahead lies Grindstone Island, but today

it's only there in our imagination.

We're in Albert County, which is rich in granite.

Large numbers of grindstones were produced on this island. The mines are

gone but the name remains.

The Bay of Fundy's own name has probably also evolved from French

(fendu, split), but there are some who believe it began as the

Portuguese word fondo (funnel). The French origin is likely, because

the Bay of Fundy is a

rift valley. It was left behind when Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were

torn apart by continental drift 200 million years ago. It's unclear

how Champlain would have known this, but the name also survives in Nova

Scotia's Cape Split.

The Bay of Fundy's own name has probably also evolved from French

(fendu, split), but there are some who believe it began as the

Portuguese word fondo (funnel). The French origin is likely, because

the Bay of Fundy is a

rift valley. It was left behind when Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were

torn apart by continental drift 200 million years ago. It's unclear

how Champlain would have known this, but the name also survives in Nova

Scotia's Cape Split.

After our first visit to Hopewell Rocks (the entrance fee is good for two

days), we enjoyed lunch at

The Tides in Alma. Alma is a quiet lobstering town at the mouth of the

Upper Salmon River; also at the eastern entrance to

Fundy National Park.

After our first visit to Hopewell Rocks (the entrance fee is good for two

days), we enjoyed lunch at

The Tides in Alma. Alma is a quiet lobstering town at the mouth of the

Upper Salmon River; also at the eastern entrance to

Fundy National Park.

Alma is also home to at least one captain who appears to be a little confused

about his nationality. The boat is registered in Saint John.

After lunch, we continued into

Fundy National Park. But the rain had resumed, so we satisfied

ourselves with the views we could get from the road, or from a few scenic

turnoffs like this one.

After lunch, we continued into

Fundy National Park. But the rain had resumed, so we satisfied

ourselves with the views we could get from the road, or from a few scenic

turnoffs like this one.

Turning around from that vista onto the Bay of Fundy, we saw Jessie teaching

herself a bit of French.

Near Sussex, we found Animaland, a sculpture park.

When the 1869 Saxby Gale destroyed Riverside-Albert's bridge over Sawmill

Creek, it was rebuilt as a covered bridge. The current covered bridge was

built in 1905, spanning 105 feet. When the province planned a concrete

bridge to replace it in 1975, the Albert County Heritage Trust acquired this

bridge and moved it to a small roadside park next to its original location.

It's one of over 60 covered bridges in New Brunswick.

When the 1869 Saxby Gale destroyed Riverside-Albert's bridge over Sawmill

Creek, it was rebuilt as a covered bridge. The current covered bridge was

built in 1905, spanning 105 feet. When the province planned a concrete

bridge to replace it in 1975, the Albert County Heritage Trust acquired this

bridge and moved it to a small roadside park next to its original location.

It's one of over 60 covered bridges in New Brunswick.

All visitors to Moncton know that they need to see the Hopewell Rocks. When we arrived at the airport on a virtually deserted Saturday, we got a little more education from somebody else with a grandchild. At Moncton, I was unprepared for the fact that the FBO is completely empty on weekends. Fortunately, the facility was unlocked, at least on the ramp (airport) side. Also fortunately, it's in the old terminal building that houses the control tower and the weather observer's station.

It's good that the building was open on the ramp side. Moncton was our first stop in Canada, which means that's where we cleared Customs inbound. We were four travellers with three different surnames, including two children under 18. This guaranteed us a personal meeting with Canadian Customs agents. Usually, we clear inbound by telephone, but this time they wanted to know that we had the kids with their parents' consent. Happily, we had letters attesting to that fact. These were the only things the Customs agents really wanted to see, besides everyone's passports.

The agents came to the GA side of the airport, only to find themselves locked out. We were just as surely locked into our side, because the FBO was closed for the weekend. So we let the guys into the building, conducted our business, and they went on their way. It's as close as you can get to amusing, under the circumstances.

The weatherman was the only person in the building where we found ourselves on arrival at Moncton. After a bit of pilot-geek conversation (he still has to measure the cloud ceiling by timing a helium balloon), we learned that he had spent the previous weekend taking his own grand-daughter, about Jessie's age, to Hopewell Cape and Alma. He mentioned that they had included Cape Enrage in their itinerary. He was a little unclear on the name, though. He thought it might have been called "Angry Cape", but he got his point across.

The weatherman's memory wasn't very far off. Cape Enrage is another place

whose name began as something else in French, but this time not much has

been lost in the translation. Cape Enrage guards the entrance to Chignecto

Bay, but it's an angry guard; there have been many shipwrecks in the area.

Barn Marsh Beach is a quiet counterpoint to the place's reputation.

The beach is covered for the four hours surrounding high tide, but it's a very

pleasant spot at other times.

The weatherman's memory wasn't very far off. Cape Enrage is another place

whose name began as something else in French, but this time not much has

been lost in the translation. Cape Enrage guards the entrance to Chignecto

Bay, but it's an angry guard; there have been many shipwrecks in the area.

Barn Marsh Beach is a quiet counterpoint to the place's reputation.

The beach is covered for the four hours surrounding high tide, but it's a very

pleasant spot at other times.

We arrived there on a beautiful, blue-sky morning. As we approached the bay

shore, the temperature approached the dewpoint, and we found ourselves in a

world of mist. It felt a bit like we were sneaking up on an alien world.

The stones above the low-tide line are all smooth,

polished by the twice-daily motion of the tide.

We arrived there on a beautiful, blue-sky morning. As we approached the bay

shore, the temperature approached the dewpoint, and we found ourselves in a

world of mist. It felt a bit like we were sneaking up on an alien world.

The stones above the low-tide line are all smooth,

polished by the twice-daily motion of the tide.

While Barbara and Jessie looked for fossils, Josh built an

inuksuk. During this time, the local weather improved

considerably.

While Barbara and Jessie looked for fossils, Josh built an

inuksuk. During this time, the local weather improved

considerably.

As we drove down to the Cape, we saw several recreational vehicles, many of them towing smaller vehicles. We met a few of the drivers while we were at this beach. They're part of an organized RV tour that was making its way through the Maritimes to Newfoundland. We spoke with one couple who had been on the road for two months already, coming from Texas. The next day, they were planning to drive to Cape Breton Island. Funny, we were going to C.B.I. ourselves the same day; but in an airplane, not in a motor home.

After a peaceful hour on the sand beach, we followed this car over the

ridge to the Cape Enrage Light.

After a peaceful hour on the sand beach, we followed this car over the

ridge to the Cape Enrage Light.

The original Cape Enrage Light, the first on Chignecto Bay, was built in 1840. Because it was an onshore light, only one keeper was hired, at a salary of £85 for the year 1854. This site was chosen over a matching site on the Nova Scotia side of Chignecto Bay because the other side iced over sooner, forcing traffic closer to Cape Enrage.

A new lighthouse was built in 1870, 160 feet above mean high water (53

feet more to mean low tide!). The old tower was converted to the keeper's

house.

A new lighthouse was built in 1870, 160 feet above mean high water (53

feet more to mean low tide!). The old tower was converted to the keeper's

house.

In November 1871, a strong storm severely battered the light station. The keeper's house was damaged beyond repair, so a new one was built. The new dwelling served until 1952, when the current house was built.

Lightning struck this lighthouse in 1876, but the damage was repaired. The present lighthouse was built in 1904. The lighthouse was automated about 25 years ago; the last keeper left in 1988. The property deteriorated quickly after that, and by 1993 the Canadian government had scheduled all buildings except the lighthouse for demolition. A group of Moncton students formed the Cape Enrage Interpretive Centre, which restored the site and maintains it today.

The site was restored as an adventure center. The thrills pay the bills to

maintain the historic buildings. With the advent of GPS navigation, mariners

are not so dependent on the light to avoid the rocks at its base.

The site was restored as an adventure center. The thrills pay the bills to

maintain the historic buildings. With the advent of GPS navigation, mariners

are not so dependent on the light to avoid the rocks at its base.

Visitors are free to explore them, however, especially at low tide. Signs change every day to remind us what time to get clear of the beach before the water comes in.

Here are four views, closer and closer, of the headland just inside the Cape Enrage Light.

Twice a day, these people have about a six-hour window to appreciate their stroll

on the Bay of Fundy's floor.

The path to the tidal flats is fairly easy, until you come to this staircase.

Like her brother, Jessie built a couple of inuksuit. These artworks will be

destroyed when the tide comes in, but that's why we have our memory. Jessie

obviously likes the caves. Her grandmother had other ideas, so she didn't

stay there very long.

Scenes like this one remind us that there is a very real danger of

rockslides in this evolving landscape.

Low-tide sightseeing at Cape Enrage. We weren't there at high tide, but the

entrance ticket there is also good for two consecutive days.

This area is rich in fossils. From a sign nearby,

The fossils at Cape Enrage are contained in layers of sedimentary rock approximately 320 million years old. All fossils at Cape Enrage have been transported from elsewhere. Tree trunks were washed downstream and deposited in logjams along the sides of large river channels. A diverse flora exists at Cape Enrage, with lowland plants including beautifully preserved giant horsetail-like trees called Calamites and classic lycopsid bark (Lepidodendron and Sigillaria) and roots (Stigmaria). An abundance of frond stems with ropey bark textures and large branch knots are preserved within the fossilized river channels associated with ~30 foot long trunks. Oftentimes, these Cordaites trees are exposed in cross section displaying the central vascular bundles (termed Artisia). Fusain (charcoal) clasts noted within the river channels demonstrate wildfires [that] were part of this carboniferous ecosystem.

The cliff section displays predominantly river dominated (fluvial) sediments. Multiple sandstone and mudstone infilled river channels can be seen in cross section along the coastline. Where channels are exposed beautiful rippled surfaces are displayed. Large scale cross bedding (angles layers of sandstone draped over each other like shingles) is observed within some layers of sandstone. These structures are interpreted as point bars, which suggest laterally migrating river channels. Localized conglomerates (sandstones with well rounded pebbles) can be found deposited in he centre of river channels where water flow was at its strongest or during flash floods.

Remember all of those steps? They're still there on the way back up.

Let's take a rest. After we climbed those stairs, we

took a late lunch at the Interpretive Center's outstanding

restaurant, featuring good local beer and wine, and fiddleheads. Then we

watched people zip-lining past the patio. Jessie was captivated. Soon after

she returned home, she went zip-lining to celebrate her twelfth birthday.

Remember all of those steps? They're still there on the way back up.

Let's take a rest. After we climbed those stairs, we

took a late lunch at the Interpretive Center's outstanding

restaurant, featuring good local beer and wine, and fiddleheads. Then we

watched people zip-lining past the patio. Jessie was captivated. Soon after

she returned home, she went zip-lining to celebrate her twelfth birthday.

On our way back to Moncton that evening, we stopped by a pony farm near

Hopewell Cape. A few days later, one of us would leave a tribute to ponies

by the Atlantic Ocean in Nova Scotia.

The FBO at Moncton is unattended on Saturday and Sunday, and does not sell 100LL. You can tie down at the Moncton Flight College, who can sell you Avgas from their pump. What they can't do, is process credit cards – bring cash. If you don't have cash, there is an ATM in their dispatch office. This is an active flying school, which is usually attended 7 days a week. If the weather is down, they may have to cancel their academic flights, so the line personnel might go home. In summer, the line office is sometimes attended as early as 5 AM. Avgas costs $2.00 / liter. One night's parking fee was waived with the fuel purchase. That's all we used there, so I don't know how much more nights would have cost.

Since 2001, the airlines all use the brand-new terminal on the north side of the airport. All GA facilities, including the FBO and the flight college, are on the south side. All of the car rental agencies are in the airline terminal. None will deliver a car to the GA side, not even Enterprise. It's about a 10-minute drive around between airline and GA facilities. The rental agencies will let you leave your car on the GA side when you're done with it, but they insist on manually swiping your card before handing you the keys when you take the car.

The next morning started with rain, and low overcast that was forecast to cover the Maritimes for the next 36 hours or more. We were headed to a place where most of our interest was indoors, so the rain didn't slow us down much. But we would not have complained if it were a sunny day.

Our destination was Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, served by the airport at Sydney. This airport is known for frequent, persistent fog, making it difficult to predict exactly when or if a pilot will be able to land there. On our departure day, the forecast showed that the weather would improve to a 600-foot ceiling for a few hours, so we aimed to arrive within that window. By the time we got from our hotel to the Moncton airport, it was raining steadily. I got pretty well soaked while getting the plane ready to go.

We were above the clouds and in the clear

en route, and had our only glimpse of the ground over Prince Edward Island and

part of Cape Breton Island. Here we see Ram Island and the Hillsborough

River just east of Charlottetown, P.E.I.

We were above the clouds and in the clear

en route, and had our only glimpse of the ground over Prince Edward Island and

part of Cape Breton Island. Here we see Ram Island and the Hillsborough

River just east of Charlottetown, P.E.I.

Half an hour later, we flew over Inverness, Nova Scotia, on the Gulf of

St. Lawrence. Then it was back into the clouds for our descent into

Sydney. We landed there under a 500-foot ceiling, which reverted to a

zero-foot ceiling a couple of hours afterward.

Half an hour later, we flew over Inverness, Nova Scotia, on the Gulf of

St. Lawrence. Then it was back into the clouds for our descent into

Sydney. We landed there under a 500-foot ceiling, which reverted to a

zero-foot ceiling a couple of hours afterward.

Sydney's airport has no FBO. Enter the airline terminal freely (one-way door), and find the uniformed Commissionaire for access back to the ramp. You can tie down on one side of the ramp, or chock your plane on the other side, which is more convenient to the terminal. You will not be admitted to the ramp while the airline is boarding or discharging passengers. Landing and parking fee (one night) totalled $27.95 with tax. Avgas costs $2.00 / liter.

We chocked the plane on the non-tiedown side, and the Commissionaire opened the vehicle gate so we could drive up to the plane for loading and unloading.

NOAA's skew-T plots include some Canadian stations. Sydney isn't covered, but Charlottetown and Moncton are. This forecast was very helpful in choosing a comfortable cruising altitude.

When we think of industry in Atlantic Canada, fishing comes naturally to

mind. But Nova Scotia also provided the resource that fueled

the Industrial Revolution in Canada, namely coal. The Sydney Coal Field

has Canada's only metallurgical coal east of Alberta. So it is fair to

say that Cape Breton Island supplied the raw material behind the industrial

development in the rest of the country.

When we think of industry in Atlantic Canada, fishing comes naturally to

mind. But Nova Scotia also provided the resource that fueled

the Industrial Revolution in Canada, namely coal. The Sydney Coal Field

has Canada's only metallurgical coal east of Alberta. So it is fair to

say that Cape Breton Island supplied the raw material behind the industrial

development in the rest of the country.

Coal was first discovered in the area in 1672 when French explorer Nicholas Denys saw a mountain of it near present-day Sydney. Fifty years later, the first commercial mine opened at Port Morien on Cow Bay. That mine supplied coal to Boston, and to the French forces building their fortress at Louisbourg. In the early 19th century the General Mining Association, a syndicate of British investors, built workshops and houses, a foundry, and a railroad to serve the mining industry here. In 1856 the GMA surrendered its rights to the coal field and the Province of Nova Scotia invited bids for leases. Over the next forty years, more than 30 mines were opened. In 1894, the government gave exclusive rights to Dominion Coal Company, an American conglomerate. By 1912, the company had 16 collieries in full operation, producing millions of tons annually – 40% of Canada's coal.

Eventually, the coal on the surface was mined out, and the miners had to go underground. The coal deposits run as far as Newfoundland, 90 miles away, but mining reaches a limit long before that. The miners need to breathe, so air must be supplied to the tunnels. It's not practical to force air more than six or seven miles down the tunnel, so that's how far the mines went. Today the mines are depleted, but most of the coal is still out there, waiting for miners to figure out how to get to it.

Francis Gray was President of the Mining Society of Nova Scotia in 1927 and 1928. He was one of the first to advocate mining the coal under the ocean floor. In his landmark paper Mining Coal Under the Sea in Nova Scotia, he said

The coal mined in Nova Scotia, has for generations, gone to provide the driving power for the industries of Quebec and Ontario. For almost a century, Nova Scotia has been exporting the raw material that lies at the base of all modern industry.

We toured the

Cape Breton Miners' Museum, which has several areas to explain

the lives and jobs of the miners and their families. The

statue at the entrance to the museum reminds the visitor that the men (women

were not allowed in the mines, ever) could rarely stand up straight on the job.

Because of low ceilings in the mines, most of them had to crawl to work.

We toured the

Cape Breton Miners' Museum, which has several areas to explain

the lives and jobs of the miners and their families. The

statue at the entrance to the museum reminds the visitor that the men (women

were not allowed in the mines, ever) could rarely stand up straight on the job.

Because of low ceilings in the mines, most of them had to crawl to work.

Just getting to and from the coal could take a large part of the miner's day. He was not productive during this time, and was not paid for it. The mining village was a textbook example of the "company town", where all aspects of life were arranged to enslave the miner in a life of indebtedness. During our brief tour, we were to hear many stories of incredible exploitation.

We suited up (sort of) and joined the tour of the museum's Ocean Deeps

Colliery.

This was never a working mine – its entrance is right in the

museum's main building.

We suited up (sort of) and joined the tour of the museum's Ocean Deeps

Colliery.

This was never a working mine – its entrance is right in the

museum's main building.

Abbie Michalik was our guide. Like all of the museum's tour guides, he's a

retired miner. He worked in the mines for 40 years, starting at 16 when he was

needed to help support his family. In 1993, the last mine closed

and put him out of a job. He briefed us on safety in the mine, and told us

stories about his life at home and on the job. Our equipment for the tour

included hard hats and walking sticks.

Abbie Michalik was our guide. Like all of the museum's tour guides, he's a

retired miner. He worked in the mines for 40 years, starting at 16 when he was

needed to help support his family. In 1993, the last mine closed

and put him out of a job. He briefed us on safety in the mine, and told us

stories about his life at home and on the job. Our equipment for the tour

included hard hats and walking sticks.

It was not long before we learned why, because we needed both

of these tools under the five-foot ceilings in the mine.

The colliery is a faithful replica of a 1932

room-and-pillar mine. It's easy to get the feeling of being in the real

thing, five miles out to sea and 2000 feet beneath the floor of the Atlantic

Ocean. In room-and-pillar mining, coal pillars were left unmined, to support

the ceiling of the mine while the coal in-between was removed. When the mine

reached the end of the seam, the pillars were also mined from the end back to

the entrance, collapsing that mine shaft in the process.

It was not long before we learned why, because we needed both

of these tools under the five-foot ceilings in the mine.

The colliery is a faithful replica of a 1932

room-and-pillar mine. It's easy to get the feeling of being in the real

thing, five miles out to sea and 2000 feet beneath the floor of the Atlantic

Ocean. In room-and-pillar mining, coal pillars were left unmined, to support

the ceiling of the mine while the coal in-between was removed. When the mine

reached the end of the seam, the pillars were also mined from the end back to

the entrance, collapsing that mine shaft in the process.

Pit ponies pulled the rail cars that carried coal out of the mine.

What a lousy

job! Once it went into the mine, the pony never saw daylight again

for the rest of its life. But it still got better treatment than the

miners. The stables had seven-foot ceilings to give the animal some room

to stretch after working all day with its head lowered. These places were

kept as clean as possible, all things considered.

Pit ponies pulled the rail cars that carried coal out of the mine.

What a lousy

job! Once it went into the mine, the pony never saw daylight again

for the rest of its life. But it still got better treatment than the

miners. The stables had seven-foot ceilings to give the animal some room

to stretch after working all day with its head lowered. These places were

kept as clean as possible, all things considered.

Abbie told us the sad story of one pit pony that did get his day in the sun. He got sick in the mine, and had to be brought to the surface while he recovered. At first, he had to be fitted with blinders against the bright light. Then he got used to life on top of the Earth. When the pony was well again, it took a small army of miners to "persuade" him to go back down to work.

Fred was an ill-tempered horse, maybe because rats had

eaten his left ear. Rats were not all bad, though.

Fred was an ill-tempered horse, maybe because rats had

eaten his left ear. Rats were not all bad, though.

Throughout the mine, there are trap doors. Air must be forced into the mine to keep the animals (horses and men, in that order) alive. The doors steer the air to where the it's needed, with disastrous consequences if they're open for too long. But sometimes they must be opened to let things pass through – tools, workers, coal, …. A trapper boy had the entry-level job (50¢ / day) of watching the door all day. When somebody needed the door open, he made sure it was only opened for the briefest possible time. Most of his shift was spent in total darkness and in utter, complete boredom.

While the trapper boy was waiting for his next burst of activity, he had to endure the rats scurrying about his feet, trying to get up his pant legs for a nibble. He wasn't allowed to kill the rats, because they had a crucial role in the mine. If the rats started to head for the surface, the boy was to warn the miners and then run after the rats; the only reason they would have for this exodus was lack of oxygen.

On a brighter note, some of the miners planted gardens in the mines.

We sat around this one while Abbie told us how his father had built the

house where he spent his childhood.

On a brighter note, some of the miners planted gardens in the mines.

We sat around this one while Abbie told us how his father had built the

house where he spent his childhood.

When Abbie was a boy, the company installed indoor toilets in all

their town's houses. This meant the outhouses were no longer needed, so his

father asked about acquiring the wood from the outhouses. The boss said that

would be fine, but it was company wood and he would have to pay for it. His

father computed how many outhouses he would need to get enough wood to build a

house, and bought that amount. Then he took them apart (salvaging the

nails!), and built himself a

house. Our guide, and his nine brothers and sisters, grew up in a

recycled outhouse.

The main reason for our visit to Glace Bay was to hear the

Men of the Deeps in concert. This choral group has two rules for

membership, in order:

The main reason for our visit to Glace Bay was to hear the

Men of the Deeps in concert. This choral group has two rules for

membership, in order:

• you must be, or have been, a working coal miner; and

• you should be able to sing.

The house lights went down, and the men filed in with their head lamps

burning. When the lights came up, we could see they were all dressed for

work. But this evening, their only work was to keep us entertained.

The only member of the Men of the Deeps who may break the rule of coal mining

experience is their musical director, Jack O'Donnell, shown here conducting.

He is a skilled narrator, explaining the history of the group and a little

bit about the songs they sing. About halfway through their performance, the

group took a break while their senior vocalist told some mining stories. He

recalled that he had been a manager in the mine, and that the man standing

next to him in the choir had been a union steward: "the only time in history

that union leadership and management have been known to sing together in

harmony." During this monologue, everyone else in the choir came down and sat

among the audience. Nice touch.

The only member of the Men of the Deeps who may break the rule of coal mining

experience is their musical director, Jack O'Donnell, shown here conducting.

He is a skilled narrator, explaining the history of the group and a little

bit about the songs they sing. About halfway through their performance, the

group took a break while their senior vocalist told some mining stories. He

recalled that he had been a manager in the mine, and that the man standing

next to him in the choir had been a union steward: "the only time in history

that union leadership and management have been known to sing together in

harmony." During this monologue, everyone else in the choir came down and sat

among the audience. Nice touch.

When we left the museum after the concert, it was pouring down rain, and we got a little lost finding our way out of Glace Bay. GPS to the rescue. This was almost the last foul weather we saw on our trip.

If you continue east from Cape Breton Island, you'll get to Newfoundland.

That wasn't in the plan, so we headed west for Digby instead. After a little

bit of delay because of some

IFR arrivals into the Sydney airport, the controller said those magic

words, "N9478N, would you be interested in direct Digby?" Of course we would!

Along the way, we passed Falmouth, N.S., on the Avon River, which feeds the

Minas Basin. Back to the land of Very High Tides.

If you continue east from Cape Breton Island, you'll get to Newfoundland.

That wasn't in the plan, so we headed west for Digby instead. After a little

bit of delay because of some

IFR arrivals into the Sydney airport, the controller said those magic

words, "N9478N, would you be interested in direct Digby?" Of course we would!

Along the way, we passed Falmouth, N.S., on the Avon River, which feeds the

Minas Basin. Back to the land of Very High Tides.

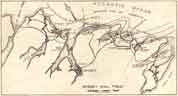

on to Digby

Moncton

Hopewell Rocks

Cape Enrage

Glace Bay

Digby

Port Royal

Annapolis Royal

Balancing Rock

Bear River

Halifax

Peggy's Cove

Blue Rocks

Lunenburg

Home