Cranes are among the tallest flying birds in the world, and most graceful in flight. Their technique and efficiency at formation flying are paragon for pilots and cyclists. Like a cyclist's draft line, all but the lead bird fly where they'll be pulled forward. Now and then, the leader drops to the end of the line and another bird takes a turn at pulling the flock.

Eleven species are endangered, some more critically than others. The case of the whooping crane is legend, and the Siberian crane is in similar straits. The red-crowned crane once bred on all four main islands of Japan; by the 1890s, it was found only on eastern Hokkaido, where a 1924 census found only twenty birds.

Why do so many die? Most of the causes are related to interaction with humans.

Valiant rescue and preservation efforts are underway, notably by the International Crane Foundation, featured in the main article in this section. Their innovative, dedicated work has restored whooping cranes from barely a dozen birds in the 1940s to about 750 in 2018. As they say, it's a big step in the right direction.

Cranes have been seen carrying stones while flying long distances. Some observers think this is to provide a smoother ride in turbulence. It may also be a "speed mod," which is not intuitive to those who are naive about aerodynamics. There is one angle of attack that is most efficient for flight, and it's independent of weight. This angle will be achieved at higher speed with more weight, not less. Racing glider pilots have long exploited this knowledge by carrying water ballast, which they dump just before landing.

Some facts about cranes have enriched our everyday language.

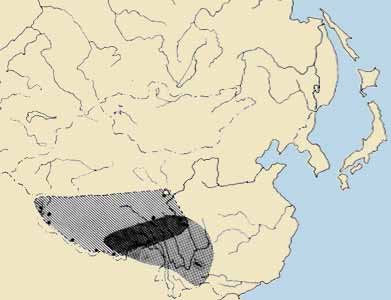

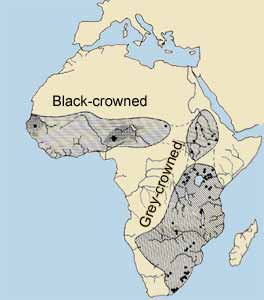

There are fifteen known species of cranes in the world. There are two subfamilies, the typical (Gruinae) and crowned (Balearicinae) cranes — the distinction should be obvious from the pictures here. Some authorities consider all crowned cranes to be one species, but most recognize a difference between black-crowned and grey-crowned cranes.

In 2010, Krajewski et al. published their DNA study, which challenged the current taxonomy of crane species. In particular, they found that the genus Grus was not monophyletic. That is, the birds in Grus didn't all have a common immediate ancestor — on the taxonomic family tree, they were more like "second cousins" than "first cousins." So they reinstated the 19th-century genus Antigone, which had been abandoned, and assigned four species to it. They also reassigned the wattled crane to Grus, and created a new genus Leucogeranus for the endangered Siberian crane.

This table shows the classification of the crane species, as they were given at the time we visited ICF and as they are now. The ones that were reassigned are marked with a bullet (•). In the main article, the modern taxonomy is used.

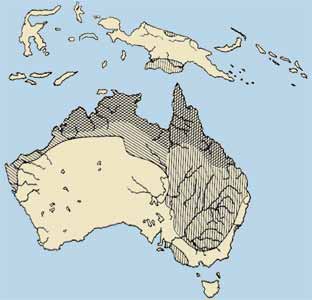

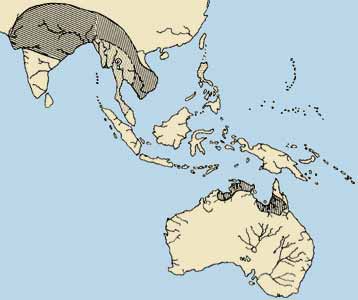

The names of the cranes are links. Click on it to jump to a map of that bird's distribution.

| Name | 2004 | 2018 | |

| Black-crowned crane | Balearica pavonina | Balearica pavonina | |

| Black-necked crane | Grus nigricollis | Grus nigricollis | |

| Blue Crane | Anthropoides paradisea | Anthropoides paradisea | |

| • | Brolga | Grus rubicunda | Antigone rubicunda |

| • | Demoiselle crane | Anthropoides virgo | Grus virgo |

| Eurasian crane | Grus grus | Grus grus | |

| Grey-crowned crane | Balearica regulorum | Balearica regulorum | |

| Hooded crane | Grus monachus | Grus monacha | |

| Red-crowned crane | Grus japonensis | Grus japonensis | |

| • | Sandhill crane | Grus canadensis | Antigone canadensis |

| • | Sarus crane | Grus antigone | Antigone antigone |

| • | Siberian crane | Grus leucogeranus | Leucogeranus leucogeranus |

| • | Wattled crane | Bugeranus carunculatus | Grus carunculatus |

| • | White-naped crane | Grus vipio | Antigone vipio |

| Whooping crane | Grus americana | Grus americana |

The main article emphasizes whooping cranes because it features the International Crane Foundation. The whooper has been brought back from the brink of extinction, but the Siberian crane is in the same precarious condition in Russia. Unfortunately, one branch of that species is effectively extinct.

There are two distinct populations of the Siberian crane. The eastern flock breeds in Yakutia (northeastern Siberia) and migrates to spend the winter near Poyang Lake (Yangtse River) in China. The western flock was not discovered until 1978, when fourteen birds were observed. They breed in the floodplain of the Ob River in northwestern Siberia. Historically, they wintered near Bharatpur in northern India, and along the south shore of the Caspian Sea. The western flock is basically extinct: only a single bird remains. His name is Omid (Persian for hope), and his arrival is eagerly awaited every year in Fereydunkenar, a small town in northern Iran.

The migration path of the eastern flock is entirely within Russia and China, so it has been easy and effective to protect them by government controls. This flock has actually grown: from a few hundred when Paul Johnsgard published Cranes of the World in 1983, to about 3600 birds in 2018.

The western flock is not nearly so lucky. What was once its main migration path passes through Afghanistan and Pakistan, which have been in some state of warfare or lawlessness for the past thirty years. Those two countries are not party to any wildlife management treaties, and hunters there have exterminated the Siberian cranes who formerly used their airspace. Some were shot; some were snared with bolas.

There was an effort to raise Siberian cranes in captivity at Keoladeo National Park, the former wintering grounds in India. The birds were released into the wild, but did not survive their first migration. Siberian cranes have not been seen in India since 2002.

The Caspian Sea group was down to three birds about four years ago, when poachers shot two of them. Now, it's only Omid.

Encouraged by their success in Wisconsin, the International Crane Foundation joined the governments of four nations in the Siberian Crane Wetland Project, a seven-year effort from 2003–2009. They supported telemetry and public awareness around the habitats of both Siberian crane flocks, eventually shifting their emphasis to the eastern flock where there was some chance of success. Within those parameters, they did indeed meet their (rolled-back) goals.

For the western flock, Russian scientists and the ICF started the Flight of Hope project, modelled on the whooping crane revitalization in the US. Cranes were bred and reared at the Oka Breeding Center near Moscow. Then they were taken to their traditional breeding ground, from which the team tried to establish them on their ancestral migration path. Like the ICF in the US, they used ultralight aircraft to teach the captive-bred cranes where to go. Even President Vladimir Putin got into the act (he's a trained pilot). Sadly, the birds didn't catch on, and the project was abandoned.

Siberian cranes can live more than eighty years. We don't know how old Omid is, but when his time comes the western flock will be gone for good. Meanwhile, the people of Fereydunkenar keep watching for him each year.

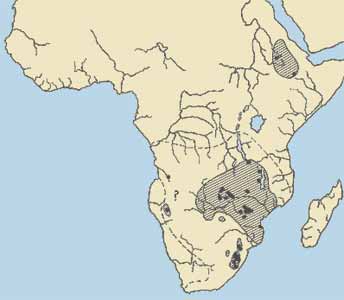

Cranes live in wetlands and grasslands of all continents except South America and Antarctica. Some species are sedentary or "resident," while others may migrate hundreds or thousands of miles between wintering and breeding grounds.

Distribution maps would take too much space in the main article, so they're given here. They are adapted from the maps in Johnsgard's Cranes of the World.

anon., Crane (bird), wikipedia.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

Johnsgard, Paul A., Cranes of the World, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1983.

Krajewski, Carey, Sipiorski, Justin T., and Anderson, Frank E., " Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences and the Phylogeny of Cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae)," The Auk 127(2):440, 2010.

Walkinshaw, Lawrence, Cranes of the World, Winchester, New York, 1973.