Home

Saugatuck

Burlington

Geodes

Nauvoo

Convention

Tiedowns

Beaumont

Hutchinson

Lucas

Dodge City

Hot Springs

Garvan Gardens

Crater of Diamonds

Petit Jean

Gastons

Cahokia Mounds

to the story's beginning back to the convention

Our next stop was the Beaumont Hotel in Kansas, about 50 miles east of

Wichita. No fuel is available at Beaumont, so a little flight planning is

needed. The idea is to take off light at Beaumont (the runway is long

enough, but not extravagant), but to have enough fuel on board to make it

safely to the next stop. Atchison, Kansas, was a good fuel stop to satisfy

that purpose. The airport is named for a famous aviator who was born in

Atchison. It's a very quiet place. Besides our plane, this Tri-Q was the

only plane outside.

Our next stop was the Beaumont Hotel in Kansas, about 50 miles east of

Wichita. No fuel is available at Beaumont, so a little flight planning is

needed. The idea is to take off light at Beaumont (the runway is long

enough, but not extravagant), but to have enough fuel on board to make it

safely to the next stop. Atchison, Kansas, was a good fuel stop to satisfy

that purpose. The airport is named for a famous aviator who was born in

Atchison. It's a very quiet place. Besides our plane, this Tri-Q was the

only plane outside.

Beaumont is one of those places that's special to pilots. After you land,

you're greeted by a sign that instructs you to obey the stop sign while you

taxi down the main street to the hotel.

This is the pilot's view as he leaves the airport to taxi to the hotel. The

airstrip was built in the 1950s, while Beaumont was still a cattle trading

town. It was for the convenience of brokers who could fly in and make their

deals there. At the time, there was still a railway station across from the

hotel.

Beaumont is one of those places that's special to pilots. After you land,

you're greeted by a sign that instructs you to obey the stop sign while you

taxi down the main street to the hotel.

This is the pilot's view as he leaves the airport to taxi to the hotel. The

airstrip was built in the 1950s, while Beaumont was still a cattle trading

town. It was for the convenience of brokers who could fly in and make their

deals there. At the time, there was still a railway station across from the

hotel.

The water tower was built in 1885 to serve the Frisco line, which carried cattle between Ellsworth, Kansas, and St. Louis. Beaumont was the highest point on the line. After climbing the hill from Piedmont ("foot of the mountain") to Beaumont, the locomotive had used so much water that it needed to stock up for the rest of the run. The cypress water tower still functions, and is believed to be the last of its kind remaining in the United States. Renovated in 1989-98, it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When itinerant railroad crews stayed in town, only white men slept in the

hotel. If you were not white, you could sleep in the yellow building behind

the store, or you could sleep outdoors.

When itinerant railroad crews stayed in town, only white men slept in the

hotel. If you were not white, you could sleep in the yellow building behind

the store, or you could sleep outdoors.

In Beaumont's heyday, there were holding pens for 9000 cattle across from the hotel, eight trains passed through every day. 1500 people lived here, and the place was a typical old western town. Then cattlemen started moving their livestock on trucks rather than by rail.

Time passed Beaumont by, and the railroad didn't survive. Now there are fewer

than 100 people living here, and the hotel is the town's only business — not

even a grocery store. The "Beaumont"

sign is still there, but the tracks have been torn up. The circle shows

either the beginning or the end of the line, depending on how you want to

think about it. In the background, barely visible, hundreds of ties

that will never be used are stacked by the tracks. The Elk River Wind Farm

now stands where the cattle pens once were.

Time passed Beaumont by, and the railroad didn't survive. Now there are fewer

than 100 people living here, and the hotel is the town's only business — not

even a grocery store. The "Beaumont"

sign is still there, but the tracks have been torn up. The circle shows

either the beginning or the end of the line, depending on how you want to

think about it. In the background, barely visible, hundreds of ties

that will never be used are stacked by the tracks. The Elk River Wind Farm

now stands where the cattle pens once were.

Not counting the state highway north of town, there are only three paved

roads. It's hard to imagine that this was a boom town just sixty years ago.

The street sign marks the intersection of 116th and Wildgrass. 116th

Street? The town has six streets in one direction and five in the other. I

wonder where they started counting streets.

Not counting the state highway north of town, there are only three paved

roads. It's hard to imagine that this was a boom town just sixty years ago.

The street sign marks the intersection of 116th and Wildgrass. 116th

Street? The town has six streets in one direction and five in the other. I

wonder where they started counting streets.

As we walked around one corner, the house seemed to be in pretty rough shape.

The hotel, however, is in fine shape. It was completely renovated in 2001.

Every room has all the amenities you'd expect of any big-city business hotel,

including wireless internet access and a refrigerator.

A sign in the parking area advises caution, but reasonable pilot technique is

plenty good enough. The reward is to tie down for the night, directly

opposite your room in the hotel. I might not have bothered with the

tiedowns, but the wind was steady over 20 knots southerly when we landed.

The forecast, and actual, wind for the next morning was over 15 knots

northerly. So I put the tiedowns in.

Three gatherings were planned during our stay. Two of them

happened. There was to be a fly-in breakfast, but the weather was too low for

any VFR activity until almost noon. A Gold Wing club and a Corvette club

from Wichita both showed up, and the Beaumont Hotel's dining room was full.

Three gatherings were planned during our stay. Two of them

happened. There was to be a fly-in breakfast, but the weather was too low for

any VFR activity until almost noon. A Gold Wing club and a Corvette club

from Wichita both showed up, and the Beaumont Hotel's dining room was full.

Here we are, representing the fly-in that got rained out. It's The Thing To

Do in Beaumont, getting a picture with the water tower. Just before we left,

some Boy Scouts rode into town and expressed an interest in the airplane.

Two of them were working on the Aviation merit badge. We let them occupy the

front seats while we chatted for a bit. The weather still wasn't really good

enough to give them a sightseeing ride. Maybe they'll come back on a nicer

flying day.

Here we are, representing the fly-in that got rained out. It's The Thing To

Do in Beaumont, getting a picture with the water tower. Just before we left,

some Boy Scouts rode into town and expressed an interest in the airplane.

Two of them were working on the Aviation merit badge. We let them occupy the

front seats while we chatted for a bit. The weather still wasn't really good

enough to give them a sightseeing ride. Maybe they'll come back on a nicer

flying day.

Near the airstrip, we saw dragonflies of a type we don't have in Connecticut.

This is as good a place as any, to tell about the Beaumont Hotel's ghost.

In the words of the present proprietor, one of the early hoteliers "worked

downstairs, while his wife worked upstairs" - meaning she was in the skin

trade. In an old-West boom town, this kind of relationship was not unusual.

But the hotel man didn't like one of her customers because he thought she was

getting attached to him. One night, that customer was somehow shot to

death, and his ghost is said to inhabit the room where it happened.

Near the airstrip, we saw dragonflies of a type we don't have in Connecticut.

This is as good a place as any, to tell about the Beaumont Hotel's ghost.

In the words of the present proprietor, one of the early hoteliers "worked

downstairs, while his wife worked upstairs" - meaning she was in the skin

trade. In an old-West boom town, this kind of relationship was not unusual.

But the hotel man didn't like one of her customers because he thought she was

getting attached to him. One night, that customer was somehow shot to

death, and his ghost is said to inhabit the room where it happened.

It's a short flight from Beaumont to Hutchinson, 40 minutes or so. We took advantage of a break in the weather to hop over there, but the controller did not want to admit me to his class-D airspace unless I called Wichita Approach for coordination. He had one airplane already using his airspace, and that fellow was practicing an instrument approach. When it was time to leave the next morning, I got equally poor service from a different controller there. I'm very glad that's not my home airport.

We were in Hutchinson to visit a salt mine. Not long ago, the State of Kansas ran a contest to identify the Eight Wonders of Kansas. Two of the winners are in Hutchinson, the Kansas Underground Salt Museum and the Cosmosphere & Space Center. We only had time for one, so we chose the Salt Museum. There isn't much to do while you're waiting for your tour but look at some samples of salt on display.

Salt, or halite, is usually colorless by the time it gets to our table. In

nature, impurities may give it red, blue, or yellow color. Rock salt also

contains clay and algal impurities that give it a layered appearance. The

Hutchinson salt bed is the largest of several in Kansas. They were formed

when the shallow Permian Sea was cut off from the open ocean and evaporated.

Later, sediments covered the salt beds, and they were unknown until 1887, when

oil men discovered salt while searching for oil and gas.

Salt, or halite, is usually colorless by the time it gets to our table. In

nature, impurities may give it red, blue, or yellow color. Rock salt also

contains clay and algal impurities that give it a layered appearance. The

Hutchinson salt bed is the largest of several in Kansas. They were formed

when the shallow Permian Sea was cut off from the open ocean and evaporated.

Later, sediments covered the salt beds, and they were unknown until 1887, when

oil men discovered salt while searching for oil and gas.

We had to wait for a scheduled tour because the entire museum is 650 feet

below ground, and the elevator only holds 40 people at a time. First, we got

some safety equipment and a briefing. Everybody had to wear a hard hat and

carry a "rescuer." We were also advised not to lick the salt in the mine.

We had to wait for a scheduled tour because the entire museum is 650 feet

below ground, and the elevator only holds 40 people at a time. First, we got

some safety equipment and a briefing. Everybody had to wear a hard hat and

carry a "rescuer." We were also advised not to lick the salt in the mine.

The Rescuer is inside the black bag. It's a breathing device that converts

carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide, and might be needed if the air quality in

the mine went sour. Carbon dioxide doesn't help you breathe better, but at

least it won't kill you. Our briefer assured us these devices have never

been needed on a tour. I sure hope they check them once in a while.

The light colored object on a grey lanyard is a camera.

The Rescuer is inside the black bag. It's a breathing device that converts

carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide, and might be needed if the air quality in

the mine went sour. Carbon dioxide doesn't help you breathe better, but at

least it won't kill you. Our briefer assured us these devices have never

been needed on a tour. I sure hope they check them once in a while.

The light colored object on a grey lanyard is a camera.

Despite the apprehension of some, the people returning

from an earlier tour obviously had a good time.

It takes the double-decker elevator one minute and forty seconds to reach the

mine. That time is spent in total darkness. At the bottom, we found

ourselves in the underground labyrinth, where we got on a tram for our mine

tour. The street signs don't help much. It quickly became obvious that our

driver needed a very good sense of direction to find his way around down

there. Every once in a while the guide would ask which way we were going -

North, South, East, West. Not many people got it right.

It takes the double-decker elevator one minute and forty seconds to reach the

mine. That time is spent in total darkness. At the bottom, we found

ourselves in the underground labyrinth, where we got on a tram for our mine

tour. The street signs don't help much. It quickly became obvious that our

driver needed a very good sense of direction to find his way around down

there. Every once in a while the guide would ask which way we were going -

North, South, East, West. Not many people got it right.

As already noted, not all salt is pure white.

This exhibit shows how explosives are set into the mine walls to crack the

salt so it can be sawn into large blocks for transport. There was one of

those blocks in the

earlier photo of the Rescuer.

This exhibit shows how explosives are set into the mine walls to crack the

salt so it can be sawn into large blocks for transport. There was one of

those blocks in the

earlier photo of the Rescuer.

Some other equipment is also on display. The second photo is the business

end of an auger drill. It's a bit to hold the carbide tips.

Some other equipment is also on display. The second photo is the business

end of an auger drill. It's a bit to hold the carbide tips.

We were told that "what goes down in the mine, stays in the mine." But not

like in Las Vegas. It's just that there was no profit in hauling anything

back out of the mine but salt. Before the use of electricity and railways,

miners used mules. Once the mule went into the mine, it would never again

see daylight. When they died, the miners left them in the mine. Our tour

didn't include any mule carcasses, but it did include this truck the miners

brought down to make it easier to get around. We were told that this is a

1932 Chevy truck, with 1934 tires. We were not told when the tires were last

inflated.

We were told that "what goes down in the mine, stays in the mine." But not

like in Las Vegas. It's just that there was no profit in hauling anything

back out of the mine but salt. Before the use of electricity and railways,

miners used mules. Once the mule went into the mine, it would never again

see daylight. When they died, the miners left them in the mine. Our tour

didn't include any mule carcasses, but it did include this truck the miners

brought down to make it easier to get around. We were told that this is a

1932 Chevy truck, with 1934 tires. We were not told when the tires were last

inflated.

The dynamite boxes were put to good use, to make "gob walls." These walls

were built to control the flow of air in the mine.

The dynamite boxes were put to good use, to make "gob walls." These walls

were built to control the flow of air in the mine.

The surfaces inside the mine are extremely stable. When the government was

looking for somewhere to put radioactive waste, it investigated salt mines,

including this one. The idea is to find a hole that will eventually close

around the stuff, making it unreachable. This mine was too stable.

Floor and ceiling move together at a rate of two or three mils per year.

That's about one inch every 600 years. The exhibit shows a rod measuring

device, with a measurement gap clearly visible on the right-hand rig.

Today's measurements are taken with laser equipment.

The surfaces inside the mine are extremely stable. When the government was

looking for somewhere to put radioactive waste, it investigated salt mines,

including this one. The idea is to find a hole that will eventually close

around the stuff, making it unreachable. This mine was too stable.

Floor and ceiling move together at a rate of two or three mils per year.

That's about one inch every 600 years. The exhibit shows a rod measuring

device, with a measurement gap clearly visible on the right-hand rig.

Today's measurements are taken with laser equipment.

We got a chance to do a little mining of our own. Well, to do a little

gathering, anyway. Does the salt pile look familiar? This is an active

mine. Most of its output is used on roads and highways.

Its two biggest customers are the State of Iowa and the City of Chicago.

There were some gems to be found, though.

We got a chance to do a little mining of our own. Well, to do a little

gathering, anyway. Does the salt pile look familiar? This is an active

mine. Most of its output is used on roads and highways.

Its two biggest customers are the State of Iowa and the City of Chicago.

There were some gems to be found, though.

The weather never changes underground. It's always 68.5°F

(20.3°C) and the

relative humidity is always 42%. This is the perfect environment to store

things if you don't want them to deteriorate. So the Carey Salt Mine also

houses Underground Vault and Storage, Inc., which leases space in the

mined-out areas. When Hollywood producers talk about sending a movie to The

Vault, they're talking about Hutchinson. There are thousands of films stored

here, and other equipment from movie sets as well.

The weather never changes underground. It's always 68.5°F

(20.3°C) and the

relative humidity is always 42%. This is the perfect environment to store

things if you don't want them to deteriorate. So the Carey Salt Mine also

houses Underground Vault and Storage, Inc., which leases space in the

mined-out areas. When Hollywood producers talk about sending a movie to The

Vault, they're talking about Hutchinson. There are thousands of films stored

here, and other equipment from movie sets as well.

The Daily Planet model was used in Superman Returns (Warner Brothers,

2006). The Superman outfit was worn by Dean Cane in the TV series Lois

and Clark (WB, 1993-97).

The Daily Planet model was used in Superman Returns (Warner Brothers,

2006). The Superman outfit was worn by Dean Cane in the TV series Lois

and Clark (WB, 1993-97).

Natalie Cook (Cameron Diaz) wore this racing suit in Charlie's Angels.

The museum now houses the world's oldest living organism. Last year,

Drs. Russell Vreeland, William Rosenzweig, and Dennis Powers awakened

bacteria from spores trapped in a salt crystal at Hutchinson. Their research

indicates that cells from those bacteria were alive more than 250 million

years ago, before the time of dinosaurs. There is an exhibit to put this

time scale into perspective. It includes a calendar that represents the

total age of the earth, beginning with Creation

at New Year's Eve. On that scale, nearly

everything we know about happened in the month of December - including those

bacteria. Humans first appeared on Earth about noon on the 31st of the month.

The museum now houses the world's oldest living organism. Last year,

Drs. Russell Vreeland, William Rosenzweig, and Dennis Powers awakened

bacteria from spores trapped in a salt crystal at Hutchinson. Their research

indicates that cells from those bacteria were alive more than 250 million

years ago, before the time of dinosaurs. There is an exhibit to put this

time scale into perspective. It includes a calendar that represents the

total age of the earth, beginning with Creation

at New Year's Eve. On that scale, nearly

everything we know about happened in the month of December - including those

bacteria. Humans first appeared on Earth about noon on the 31st of the month.

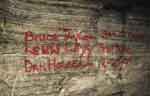

Graffiti is everywhere, even 650 feet down.

on to Lucas

Saugatuck

Burlington

Geodes

Nauvoo

Convention

Tiedowns

Beaumont

Hutchinson

Lucas

Dodge City

Hot Springs

Garvan Gardens

Crater of Diamonds

Petit Jean

Gastons

Cahokia Mounds

Home