Visits to Bard College

October 2016

October 2016

A year ago I was not familiar with Bard College, a

small liberal arts school

in Dutchess County, New York. I had a lot to learn in a hurry when Barbara's

grandson Josh first applied there, and then decided to attend.

A year ago I was not familiar with Bard College, a

small liberal arts school

in Dutchess County, New York. I had a lot to learn in a hurry when Barbara's

grandson Josh first applied there, and then decided to attend.

John and Margaret Bard bought part of the Blithewood Estate overlooking the Hudson River in 1853. They built a small wood-frame structure that served as a school during the week and a chapel on Sundays. That first building became today's Bard Hall in the heart of the campus. It's used for lectures, recitals, and classes.

These windows are in the non-denominational Chapel of the Holy Innocents

next door. This chapel and a couple of other central buildings were

the nucleus of

St. Stephen's College, which was renamed for the original benefactors in

1934. You can read detailed histories of the school on its

web site and

Wikipedia; no need to repeat much here. Over time, the original

18-acre site grew to today's

1000-acre campus. Since its founding, Bard has been home to many notable

residents and alumni — mostly in the arts and humanities, but a few

scientists as well. The school's

history site names a few of these people.

These windows are in the non-denominational Chapel of the Holy Innocents

next door. This chapel and a couple of other central buildings were

the nucleus of

St. Stephen's College, which was renamed for the original benefactors in

1934. You can read detailed histories of the school on its

web site and

Wikipedia; no need to repeat much here. Over time, the original

18-acre site grew to today's

1000-acre campus. Since its founding, Bard has been home to many notable

residents and alumni — mostly in the arts and humanities, but a few

scientists as well. The school's

history site names a few of these people.

Tivoli Bays, a large intertidal marshland, divide the north end of

campus from the Hudson River. The hiking trails of the

Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve may as well be an

extension of the college property. This view across the river to the

Catskills is at the end of a mile-long road that passes Josh's dorm.

Tivoli Bays, a large intertidal marshland, divide the north end of

campus from the Hudson River. The hiking trails of the

Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve may as well be an

extension of the college property. This view across the river to the

Catskills is at the end of a mile-long road that passes Josh's dorm.

It's not possible to discuss Bard College without including one man, Leon Botstein. When he came to Bard, Botstein was the youngest college president in the country. That was over forty years ago. He's been president ever since, another record. He is also conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra.

John Bard built the college, but Leon Botstein has made it what it is today. His innovative policies and academic courses are unique in America, and his ability to elicit generous donations from wealthy friends is responsible for much of the impressive architecture that we see here.

This aerial view shows Botstein's musical headquarters, the

Fisher Center for the Performing Arts. The building was designed by

world-renowned architect

Frank Gehry, one of Leon Botstein's many special friends and acquaintances.

This aerial view shows Botstein's musical headquarters, the

Fisher Center for the Performing Arts. The building was designed by

world-renowned architect

Frank Gehry, one of Leon Botstein's many special friends and acquaintances.

At left center we find

Olafur Eliasson's artificial island,

Parliament of Reality. This permanent installation is meant to

evoke the feeling of Iceland's parliament, the world's oldest democratic

assembly. It invites people to relax, discuss ideas, or argue.

Visitors approach the island beneath a stainless arch.

At left center we find

Olafur Eliasson's artificial island,

Parliament of Reality. This permanent installation is meant to

evoke the feeling of Iceland's parliament, the world's oldest democratic

assembly. It invites people to relax, discuss ideas, or argue.

Visitors approach the island beneath a stainless arch.

Josh's housing complex is at upper left. Because the dorms have names like Sycamore and Mulberry, students call these the Treehouses. The buildings in the middle are also dormitories, Robbins Hall and Ward Manor.

The large open plot is the Bard Farm, which produces a lot of the food used in the college's dining halls. Students are strongly encouraged to contribute their labor to this cooperative farm.

Let's have a closer look at the Performing Arts Center, and the view from the

ground. Gehry's grand curves have earned it the moniker "Potato Chip

Building." Every summer, this auditorium hosts the

Bard Music Festival. Famous performers from around the world gather to

perform great works, many of which are not usually heard. One of Leon

Botstein's passions is to showcase the good works of "under-performed"

composers.

Let's have a closer look at the Performing Arts Center, and the view from the

ground. Gehry's grand curves have earned it the moniker "Potato Chip

Building." Every summer, this auditorium hosts the

Bard Music Festival. Famous performers from around the world gather to

perform great works, many of which are not usually heard. One of Leon

Botstein's passions is to showcase the good works of "under-performed"

composers.

There is a much larger version of the second photo here.

Here's the main part of the campus. The student center and some dorms are in

the foreground. The dorms are the Alumni Residence Halls. That sounds much

too stuffy, so students just call them the Toasters. The building to the left

of the student center is for Studio Arts. There's a wall inside designed for

spontaneous acts of graffiti. Spray paint is provided, but all of the cans

were empty when we stopped by.

Here's the main part of the campus. The student center and some dorms are in

the foreground. The dorms are the Alumni Residence Halls. That sounds much

too stuffy, so students just call them the Toasters. The building to the left

of the student center is for Studio Arts. There's a wall inside designed for

spontaneous acts of graffiti. Spray paint is provided, but all of the cans

were empty when we stopped by.

Crossing to the east side of Annandale Road, we find

the serpentine science center, faculty offices and some buildings named for

Franklin Olin, and the Stevenson Library. Winchester Arms is a subsidiary of

the Olin Corporation, which produces ammunition and explosives. Mr. Olin made

a fortune producing implements of war, but his buildings are there for the

study of humanities and language.

Crossing to the east side of Annandale Road, we find

the serpentine science center, faculty offices and some buildings named for

Franklin Olin, and the Stevenson Library. Winchester Arms is a subsidiary of

the Olin Corporation, which produces ammunition and explosives. Mr. Olin made

a fortune producing implements of war, but his buildings are there for the

study of humanities and language.

Anna Margaret Jones was a popular Bard senior who was murdered on the grounds

of a local church. Bard built this meditation garden in her memory as a place

for contemplation. Two long benches are framed by Canadian hemlocks.

Large stones are engraved with poetry, and there is a fire pit.

Anna Margaret Jones was a popular Bard senior who was murdered on the grounds

of a local church. Bard built this meditation garden in her memory as a place

for contemplation. Two long benches are framed by Canadian hemlocks.

Large stones are engraved with poetry, and there is a fire pit.

As a requirement for graduation, every Bard senior must complete a

substantial project. Bob Bassler ('57) produced the sculpture

Seclusion, which was originally installed in another part of the

campus. After thirty years, Mr. Bassler reclaimed his project and made this

bronze casting, which sits in the shade near Anna Jones's garden. The

bronze reproduction is also known as the Bard Nymph.

As a requirement for graduation, every Bard senior must complete a

substantial project. Bob Bassler ('57) produced the sculpture

Seclusion, which was originally installed in another part of the

campus. After thirty years, Mr. Bassler reclaimed his project and made this

bronze casting, which sits in the shade near Anna Jones's garden. The

bronze reproduction is also known as the Bard Nymph.

More recently, Sofia Pia Belenky ('11) designed and built Circle Swing.

It's good for a few thrills, but Jessie learned that you can't ride it solo.

Without somebody to keep it in balance, the seat tilts and jams, so it won't

spin properly around the center pole. So Josh climbed on, and he got some

thrills too.

More recently, Sofia Pia Belenky ('11) designed and built Circle Swing.

It's good for a few thrills, but Jessie learned that you can't ride it solo.

Without somebody to keep it in balance, the seat tilts and jams, so it won't

spin properly around the center pole. So Josh climbed on, and he got some

thrills too.

Jessie is admiring Pol Bury's 1984 kinetic sculpture Fontaine. The

name isn't very imaginative, but the work is. Water slowly fills the tubes

one by one, until they're heavy enough to tip and spill into the pool.

Behind her, Warden's Hall is for faculty offices.

If Jessie looked up and to her right, she would see the Ionic portico of the

Stevenson Library. A major part of the library is now digital, but they

still need a place to store a few dead trees.

Jessie is admiring Pol Bury's 1984 kinetic sculpture Fontaine. The

name isn't very imaginative, but the work is. Water slowly fills the tubes

one by one, until they're heavy enough to tip and spill into the pool.

Behind her, Warden's Hall is for faculty offices.

If Jessie looked up and to her right, she would see the Ionic portico of the

Stevenson Library. A major part of the library is now digital, but they

still need a place to store a few dead trees.

Another eminent Bardian was

Hannah Arendt, namesake of the college's Center for Politics and

Humanities. As a Jew in Nazi Germany, she realized there was no future for

her there, and left in 1933. Later, she met and married poet and philosopher

Heinrich Blücher. He encouraged her interest in

totalitarianism and Marxism, for which she earned world renown. Her first

work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, is an important analysis of

human rights and freedom. Later, she aroused great controversy with

Eichmann in Jerusalem — readers thought she

apologized for Eichmann because he was "just doing his job."

Another eminent Bardian was

Hannah Arendt, namesake of the college's Center for Politics and

Humanities. As a Jew in Nazi Germany, she realized there was no future for

her there, and left in 1933. Later, she met and married poet and philosopher

Heinrich Blücher. He encouraged her interest in

totalitarianism and Marxism, for which she earned world renown. Her first

work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, is an important analysis of

human rights and freedom. Later, she aroused great controversy with

Eichmann in Jerusalem — readers thought she

apologized for Eichmann because he was "just doing his job."

Ironically, this Jewish philosopher and crusader was plagued by a lifelong love for a Nazi, Martin Heidegger. As a young student, she became his lover and allowed him to take credit for much of her own work. German politics forced an end to the affair, but she resumed it many years later after her second husband died.

Hannah Arendt died in the year Leon Botstein

assumed the presidency at Bard, but people can still visit her here.

She and her husband are buried in a small cemetery in the woods, just a few

yards north of the Olin buildings and the Stevenson Library. The cemetery

has a bench for those who would like to pause and reflect. Some joker has

wired a glove to its back — "Hold Me." So Jessie did.

Hannah Arendt died in the year Leon Botstein

assumed the presidency at Bard, but people can still visit her here.

She and her husband are buried in a small cemetery in the woods, just a few

yards north of the Olin buildings and the Stevenson Library. The cemetery

has a bench for those who would like to pause and reflect. Some joker has

wired a glove to its back — "Hold Me." So Jessie did.

The Bard College Cemetery is at the top of a hill. Students learn early that this is the best place to get a good cell phone signal if their carrier has gaps in the coverage.

There is a much

larger version of this photo

here.

Bard has no Greek system and not many organized sports. But the Raptors' soccer team has excellent fields for their competitions. They're right next to 1200 solar panels that help to keep the lights burning. Everywhere you go, there are signs that Bard College takes its responsibility to Gaia seriously.

Blithewood Manor dominates the south campus. It's on the site of John Bard's

first purchase, but he didn't live there. It was built a year after he died,

in 1900. It's home to Bard's business school, the

Levy Economics Institute.

There's an art museum next door — we'll get there soon. Major

features at Blithewood are its formal Italian garden and the goat pens in

the center foreground of the second photo. A dozen goats were recently

added to help clean up the hillside, an alternative to brush hogs and weed

eaters.

Blithewood Manor dominates the south campus. It's on the site of John Bard's

first purchase, but he didn't live there. It was built a year after he died,

in 1900. It's home to Bard's business school, the

Levy Economics Institute.

There's an art museum next door — we'll get there soon. Major

features at Blithewood are its formal Italian garden and the goat pens in

the center foreground of the second photo. A dozen goats were recently

added to help clean up the hillside, an alternative to brush hogs and weed

eaters.

John Bard sold his Blithewood estate to St. Stephen's College in 1897.

The college sold the property to one Andrew Zabriskie two years later.

Zabriskie commissioned Francis Hoppin to design the manor house and garden

that we can visit today. The college got the property back in 1951 and used

it as a women's dorm for several years, then repurposed it to house the Levy

Institute.

John Bard sold his Blithewood estate to St. Stephen's College in 1897.

The college sold the property to one Andrew Zabriskie two years later.

Zabriskie commissioned Francis Hoppin to design the manor house and garden

that we can visit today. The college got the property back in 1951 and used

it as a women's dorm for several years, then repurposed it to house the Levy

Institute.

The "All Saints" Maple on Blithewood's north lawn was judged New York's state

champion tree in 1985. How does a tree become a champion? The keepers of the

title use a formula that combines the girth of the trunk and the diameter of

the crown. The championship was lost after a lightning strike, followed years

later by a mysterious fire. Even in its crippled state, this remains one of

the largest and most distinctive trees on campus. It's estimated to be about

350 years old.

The "All Saints" Maple on Blithewood's north lawn was judged New York's state

champion tree in 1985. How does a tree become a champion? The keepers of the

title use a formula that combines the girth of the trunk and the diameter of

the crown. The championship was lost after a lightning strike, followed years

later by a mysterious fire. Even in its crippled state, this remains one of

the largest and most distinctive trees on campus. It's estimated to be about

350 years old.

Josh and Jessie are inspecting the groundskeepers. If they look past the

goat pen, they'll have a prime view of the Hudson River and Catskill

Mountains.

The fountain in the center of Blithewood's garden is where Bob Bassler's

Seclusion reigned for thirty years.

The

original cast stone sculpture now graces a koi pond at the artist's home

in California. The sprinkler head is better than nothing, but it seems a poor

substitute.

The gazebo at the end of the garden is a good place to watch trains go by, or

to just sit and savor the garden. Three or four trains passed by in the

short time we were at the garden.

The gazebo at the end of the garden is a good place to watch trains go by, or

to just sit and savor the garden. Three or four trains passed by in the

short time we were at the garden.

Across the road from the Levy Institute, we find CCS Bard, the Center for

Curatorial Studies. I suppose that means this is where you learn how to

manage a museum. By all outward appearances, it's an art museum. The part

on the right was closed when we were there because of the Fall Break.

That part of the building houses the Marieluise Hessel Collection, on

permanent loan (whatever that means) from another of Dr. Botstein's

friends, the former Miss Germany 1958. She doesn't like to discuss her age,

but one can't hide from history. Or math. (She

wears her years very well.)

Across the road from the Levy Institute, we find CCS Bard, the Center for

Curatorial Studies. I suppose that means this is where you learn how to

manage a museum. By all outward appearances, it's an art museum. The part

on the right was closed when we were there because of the Fall Break.

That part of the building houses the Marieluise Hessel Collection, on

permanent loan (whatever that means) from another of Dr. Botstein's

friends, the former Miss Germany 1958. She doesn't like to discuss her age,

but one can't hide from history. Or math. (She

wears her years very well.)

Although we couldn't see Mrs. Hessel's avant-garde collection in her half of

the museum, the left side (rounded roofs) was open to the public. This

area is used to show the disturbing paranormal exhibit of

Tony Oursler, the

"Imponderable Archive."

This is a large display of encounters between humans and the

supernatural

world. If you can't get enough of this at Bard, there is a complementary

exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. If you'd rather

short-cut the whole process, you can

buy Mr. Oursler's book, which covers the same material that's on view in

the exhibit. The book will not afford you the personal encounter we had with

a wooden mask that looked like a shrunken human head. The effect was enhanced

by incorporating human hair.

Some of the sculpture at the Hessel Museum is outdoors. If it looks like

there's a big wishbone on the front lawn, that's exactly what it is.

Mark Handforth enlarged a 3D digital image

of a chicken wishbone to be over

seven feet high, then copied it in raw aluminum.

of a chicken wishbone to be over

seven feet high, then copied it in raw aluminum.

Laube

2004

Franz West made several of these abstracts in lacquered aluminum. This

one, whose name means arbor, is about

ten feet high.

Henry Hudson was under contract to the Dutch East India Company when he

discovered New York and sailed up his namesake river to Albany. Most of the

early settlement along the river was Dutch, the county's name is

Dutchess,

and even its flag shows traditional Dutch colors. So, many of the

place names here use Dutch words — specifically, 17th-century Dutch

words. One of those words is kill, which meant a stream or creek.

This word appears wherever Hollanders settled along a stream: Catskill,

Sawkill, Kline Kill, Fishkill, ….

Henry Hudson was under contract to the Dutch East India Company when he

discovered New York and sailed up his namesake river to Albany. Most of the

early settlement along the river was Dutch, the county's name is

Dutchess,

and even its flag shows traditional Dutch colors. So, many of the

place names here use Dutch words — specifically, 17th-century Dutch

words. One of those words is kill, which meant a stream or creek.

This word appears wherever Hollanders settled along a stream: Catskill,

Sawkill, Kline Kill, Fishkill, ….

The word has nothing to do with ending a life, but PETA has taken up the cudgel to revise place names that use this antique word. Down the river from Bard, the organization is campaigning to rename Fishkill to Fishsave or Fishlove. How terribly ignorant and misdirected that is. A kill is a creek. Back to the story. This just seemed like a good place to explain the name of Sawkill Creek, which now seems a bit redundant.

Bard College was assembled by acquiring a few large, contiguous estates along the east shore of the Hudson River. Sawkill Creek is scenic, but in the 19th century it was also a valuable source of power for small factories. A few properties within the south campus along Annandale Road have not been absorbed into the college, as shown by the lighter color on this inset from Bard's map. These are mainly faculty residences. One of these sites was the location of a chocolate factory that was eventually moved to the main business district of Red Hook when the area was electrified. After that, the factory fell into ruin.

Frank Oja came to Bard in 1957 and taught psychology here until he retired in 2000. During his 43-year tenure, he was chairman of the Psychology Department. chairman of Social Services, and director of Bard's University Without Walls program. While he lived at Bard, Mr. Oja built his house on the foundation of the old chocolate factory by the Sawkill's Upper Falls. Most of the lumber was reclaimed from buildings in the abandoned Ward Manor Village in the north part of the campus.

Waterfalls

Frank Oja was buried in the Bard College Cemetery. His

widow Ruth has been an avid environmentalist and gardener. From time to time

she opens her garden to the public, where visitors can enjoy her

breathtaking view of the Upper Falls. But for the most part,

we must be content with the view looking down on the falls, behind

the faculty offices in Shafer House. This is the first of three waterfalls

on Sawkill Creek, all within the Bard campus.

Frank Oja was buried in the Bard College Cemetery. His

widow Ruth has been an avid environmentalist and gardener. From time to time

she opens her garden to the public, where visitors can enjoy her

breathtaking view of the Upper Falls. But for the most part,

we must be content with the view looking down on the falls, behind

the faculty offices in Shafer House. This is the first of three waterfalls

on Sawkill Creek, all within the Bard campus.

Zabriskie's Falls are next on the way downstream. This is also called the Bard Waterfall because it's a popular spot for students to relax. Find a short trail below the water treatment plant and duck under the ducks. The site is favored for skinny-dipping and pharmaceutical experiments, so we took a pass the first time around. We'll come back when it's too cold for swimming.

The trail is the South Bay Trail, part of the Hudson River Research Reserve system. Follow it downstream to the Sawkill's last cataract.

Sawkill's Lower Falls are easily accessible to the public, by the South Bay

Trail on the north bank

and by trails in Montgomery Place to the south bank.

They have been

attracting and inspiring artists for over two hundred years.

Sawkill's Lower Falls are easily accessible to the public, by the South Bay

Trail on the north bank

and by trails in Montgomery Place to the south bank.

They have been

attracting and inspiring artists for over two hundred years.

Jacques-Gerard

Milbert's monochrome lithograph The Lower Falls, Montgomery

Place dates from 1825.

There is at least one copy in existence (and for sale) that the artist

hand-colored.

Jacques-Gerard

Milbert's monochrome lithograph The Lower Falls, Montgomery

Place dates from 1825.

There is at least one copy in existence (and for sale) that the artist

hand-colored.

At the mouth of Sawkill Creek, someone has built the frame for a small hut

on the north bank. The water in the background is Tivoli South Bay.

Montgomery Place

Richard Montgomery distinguished himself in service to the Crown in the Seven Years War, both in North America and the Caribbean. When the American Revolution began, he took up the Patriot cause, with a commission as Brigadier General. He was highly regarded, and was deeply mourned when he was killed during the failed American invasion of Canada in late 1775.

When the war was over, his widow Janet moved into the manor they had been

building in Rhinebeck, and began plans for a mansion on riverfront property

the Montgomerys owned. Château de Montgomery was finished in 1805.

She established a working farm and orchard there, which are still

in operation. She also designed and oversaw the construction of a

Federal-style mansion that is the central part of today's manor house.

When the war was over, his widow Janet moved into the manor they had been

building in Rhinebeck, and began plans for a mansion on riverfront property

the Montgomerys owned. Château de Montgomery was finished in 1805.

She established a working farm and orchard there, which are still

in operation. She also designed and oversaw the construction of a

Federal-style mansion that is the central part of today's manor house.

The estate is named for Richard Montgomery, but its history is really that of Janet Livingston's side of the family. Her older brother Robert administered the oath of office to George Washington; her younger brother Edward was Mayor of New York and later Andrew Jackson's Secretary of State. Widowed as a young woman, Janet Livingston Montgomery died with no children. She willed her property to her brother Edward, who had visited there often with his wife and daughter.

Edward's wife Louise was no stranger to the gentle life, or to violence. She

made a hair-raising escape from

Haiti when the slaves revolted and took over, but she had

been an aristocrat before all that. She determined to bring Montgomery Place

up to the standards of the day, engaging the most prestigious architect of the

era —

Alexander Jackson Davis — to help her.

Edward's wife Louise was no stranger to the gentle life, or to violence. She

made a hair-raising escape from

Haiti when the slaves revolted and took over, but she had

been an aristocrat before all that. She determined to bring Montgomery Place

up to the standards of the day, engaging the most prestigious architect of the

era —

Alexander Jackson Davis — to help her.

Louise and Mr. Davis added three porches and the South Wing to

Janet's simple box design to produce the elegant Classical homestead we can

visit today. She added other buildings to the estate that were considered

de rigeur, including the

Louise and Mr. Davis added three porches and the South Wing to

Janet's simple box design to produce the elegant Classical homestead we can

visit today. She added other buildings to the estate that were considered

de rigeur, including the  carriage house that is the modern visitor's first

encounter with the estate. This building was part of Louise's campaign to

de-emphasize farming, although she didn't want to eliminate it entirely. The

carriage house is where Janet Livingston Montgomery's dairy barn once

stood.

carriage house that is the modern visitor's first

encounter with the estate. This building was part of Louise's campaign to

de-emphasize farming, although she didn't want to eliminate it entirely. The

carriage house is where Janet Livingston Montgomery's dairy barn once

stood.

The cupola is not just for decoration.

Not only were the carriages

kept here, but also the horses that pulled them. Ventilation was necessary.

The cupola is not just for decoration.

Not only were the carriages

kept here, but also the horses that pulled them. Ventilation was necessary.

One horse remains, near the visitor center. He doesn't need ventilation,

food, water, or shelter.

In 1841, Robert Donaldson owned the land that would become the Blithewood estate, on the north side of Sawkill Creek. That year, he and Louise Livingston bought land on both sides of the ravine and razed a mill at the mouth of the creek. They made a contract to preserve the land against industrial development in perpetuity, one of the first conservation agreements in the United States.

Louise's daughter Cora grew up in the diplomatic circles of the nation's

capital, but had spent summers at Montgomery Place as a child. She

collaborated with her mother on many of the modernizing changes to the

estate, and expanded on them in grand fashion.

Louise's daughter Cora grew up in the diplomatic circles of the nation's

capital, but had spent summers at Montgomery Place as a child. She

collaborated with her mother on many of the modernizing changes to the

estate, and expanded on them in grand fashion.

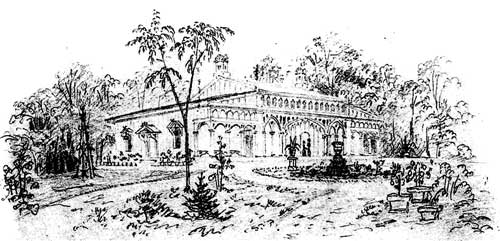

Louise had commissioned the

design of a conservatory — every proper country estate had to have one

— but Cora supervised its construction. The conservatory, and a great

deal of outdoor statuary, dominated Montgomery Place for forty years. Cora

designed formal gardens and paths around the conservatory in the best

Victorian tradition.

Her husband Thomas Barton, son of a noted naturalist,

designed the arboretum that many visitors overlook because it's "hidden in

plain sight."

Louise had commissioned the

design of a conservatory — every proper country estate had to have one

— but Cora supervised its construction. The conservatory, and a great

deal of outdoor statuary, dominated Montgomery Place for forty years. Cora

designed formal gardens and paths around the conservatory in the best

Victorian tradition.

Her husband Thomas Barton, son of a noted naturalist,

designed the arboretum that many visitors overlook because it's "hidden in

plain sight."

After Cora Barton died, her heirs decided that the conservatory was too labor-intensive (the original gardeners had once been slaves), and had it dismantled. The property lapsed into custody of distant cousins for several years, until it eventually passed to a Livingston descendant named John Ross Delafield and his wife Violetta.

Violetta White Delafield was a passionate botanist and

mycologist. There are even some

species of mushroom named for her. We saw some unusual mushrooms at

Montgomery place — one variety was as big as a dinner plate

Violetta White Delafield was a passionate botanist and

mycologist. There are even some

species of mushroom named for her. We saw some unusual mushrooms at

Montgomery place — one variety was as big as a dinner plate

— but Violetta's legacy here involves much larger plants.

She turned her attention to gardening, including a formal rose garden near

Janet Montgomery's greenhouse. The garden was rather spare for our visit,

but the sundial is in great shape. Next to that is the Ellipse, an outdoor

"room" surrounded by tall hemlocks. The pool makes the Ellipse a superb place

for reflection.

— but Violetta's legacy here involves much larger plants.

She turned her attention to gardening, including a formal rose garden near

Janet Montgomery's greenhouse. The garden was rather spare for our visit,

but the sundial is in great shape. Next to that is the Ellipse, an outdoor

"room" surrounded by tall hemlocks. The pool makes the Ellipse a superb place

for reflection.

Beyond, Violetta had a well-tended rock garden with a path

from the Ellipse to the main house. World War II called most of the

gardeners, so the rock garden evolved into the "rough garden," with

low-maintenance native plants replacing some of the previous exotic species.

One end of the path is lined with locust trees that have grown into some

interesting shapes over the past eighty years.

Beyond, Violetta had a well-tended rock garden with a path

from the Ellipse to the main house. World War II called most of the

gardeners, so the rock garden evolved into the "rough garden," with

low-maintenance native plants replacing some of the previous exotic species.

One end of the path is lined with locust trees that have grown into some

interesting shapes over the past eighty years.

Violetta made another lasting mark on the community in 1935, when she opened the farm stand that still sells Montgomery Place produce on Route 9G. She wasn't the only one in her family with a deep love of nature. Her brother Alain founded the White Memorial Conservation Center to preserve about 4000 acres of woodland near Connecticut's Bantam Lake. Since 1913, the Foundation has donated thousands more acres of woodland to the State, including six state parks and forests.

In 1923 the Delafields tapped the Sawkill's flow to run a turbine

that provided electricity for Montgomery Place, and for several buildings in

Annandale. In 1965, Montgomery Place joined the local power grid. The power

plant was kept for backup until 1983, after which it was dismantled.

In 1923 the Delafields tapped the Sawkill's flow to run a turbine

that provided electricity for Montgomery Place, and for several buildings in

Annandale. In 1965, Montgomery Place joined the local power grid. The power

plant was kept for backup until 1983, after which it was dismantled.

Today's visitor can see its

ruins near the Lower Falls, including the pipe that once fed water to the

turbine. The pipe is visible in the first old photo, on the right side of the

building.

Today's visitor can see its

ruins near the Lower Falls, including the pipe that once fed water to the

turbine. The pipe is visible in the first old photo, on the right side of the

building.

John Ross Delafield outlived Violetta by fifteen years; then their son John White Delafield moved to the estate in 1964. The financial burden of maintaining the property was overwhelming. He sold it to Sleepy Hollow Restorations, who did extensive restoration work and got Montgomery Place designated a National Historic Landmark. Bard College acquired the 380-acre estate in 2016.

This is the "back" of Château de Montgomery, the west face. It might also

be considered the "front" because it looks out onto the Hudson River. This is

the aspect that we saw in the A.J. Davis sketch

earlier, now with Louise Livingston's improvements. One only has to turn

around to see the magnificent view of the Hudson River that the Livingston

family enjoyed for over two hundred years.

This is the "back" of Château de Montgomery, the west face. It might also

be considered the "front" because it looks out onto the Hudson River. This is

the aspect that we saw in the A.J. Davis sketch

earlier, now with Louise Livingston's improvements. One only has to turn

around to see the magnificent view of the Hudson River that the Livingston

family enjoyed for over two hundred years.

The last photo is very wide. If you'd rather see a screen-sized version, it's

here.