Home

Michigan City

Sioux Falls

Billings

EBR-1

to the story's beginning back to Craters of the Moon

We're back in the air again, one last long flying day before we get to

western Washington.

For the past two days we've been looking at Big Southern Butte from the

North. As we fly by its southern face, it's easy to see how it was formed in

two distinct stages.

We're back in the air again, one last long flying day before we get to

western Washington.

For the past two days we've been looking at Big Southern Butte from the

North. As we fly by its southern face, it's easy to see how it was formed in

two distinct stages.

Here's a little airport called Cox's Well, It doesn't look like Mr. Cox

has much room to park when he flies in to visit his well.

Here's a little airport called Cox's Well, It doesn't look like Mr. Cox

has much room to park when he flies in to visit his well.

Two Idaho towns, Richfield and Shoshone.

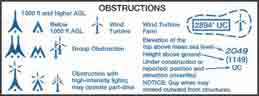

As we pass Gooding and its airport, I notice a new chart symbol. The FAA no

longer treats all obstacles equally; there's a new symbol for windmills.

They even have an aggregate symbol for a windmill farm. Flying by the

airport, the windmill farm is just starting to become apparent in the

distance.

As we pass Gooding and its airport, I notice a new chart symbol. The FAA no

longer treats all obstacles equally; there's a new symbol for windmills.

They even have an aggregate symbol for a windmill farm. Flying by the

airport, the windmill farm is just starting to become apparent in the

distance.

As we approach and pass the power plant on the Snake River, the windmills become obvious.

We have some more mountains to cross today. Leaving the Snake River at

Weiser, we find Route 26 and follow it over El Dorado Pass to John Day,

Oregon. Many features in this part of Oregon are named for the trapper we

first learned about, back in Idaho, including the town where we used

the Grant County Airport.

We flew over a lot of his route.

We have some more mountains to cross today. Leaving the Snake River at

Weiser, we find Route 26 and follow it over El Dorado Pass to John Day,

Oregon. Many features in this part of Oregon are named for the trapper we

first learned about, back in Idaho, including the town where we used

the Grant County Airport.

We flew over a lot of his route.

We knew this airport had

extraordinary amenities, but we arrived on a summer Saturday,

when the sandwich shop is closed. So we brought our own. We had bought box

lunches before we left Arco in the morning. We ate them on picnic tables

that are just barely out of this picture. We didn't eat our apples, because

they were harder than the picnic tables. The rest of our lunch was OK.

We knew this airport had

extraordinary amenities, but we arrived on a summer Saturday,

when the sandwich shop is closed. So we brought our own. We had bought box

lunches before we left Arco in the morning. We ate them on picnic tables

that are just barely out of this picture. We didn't eat our apples, because

they were harder than the picnic tables. The rest of our lunch was OK.

I was surprised to find the door open; the office is attended on Saturdays

after all. The sandwich ladies weren't there, but the line crew was. This

place looks like you could move in and live here for a while.

I was surprised to find the door open; the office is attended on Saturdays

after all. The sandwich ladies weren't there, but the line crew was. This

place looks like you could move in and live here for a while.

Like many airports in the dry West, this one is an important fire control

center.

Barbara noticed the watch tower, but we realize they get much

more information from personal inspection.

Like many airports in the dry West, this one is an important fire control

center.

Barbara noticed the watch tower, but we realize they get much

more information from personal inspection.

After lunch, we headed for Mitchell, and for Oregon's Painted Hills. This

interesting pattern was en route, a harvest in progress.

After lunch, we headed for Mitchell, and for Oregon's Painted Hills. This

interesting pattern was en route, a harvest in progress.

At Mitchell, we turned north to follow the Day River through the Painted

Hills, the last high terrain we would have to negotiate for several days.

When the hills didn't look so "painted" any longer, we headed for The Dalles

and the Columbia River.

At Mitchell, we turned north to follow the Day River through the Painted

Hills, the last high terrain we would have to negotiate for several days.

When the hills didn't look so "painted" any longer, we headed for The Dalles

and the Columbia River.

We followed the Columbia past

Hood River, Oregon, and over the Cascade Locks.

The Indians called this area Bridge of the Gods; Lewis and Clark portaged

around it in 1805.

We followed the Columbia past

Hood River, Oregon, and over the Cascade Locks.

The Indians called this area Bridge of the Gods; Lewis and Clark portaged

around it in 1805.

Before we finished our flying day, we got to admire four volcanoes.

Before we finished our flying day, we got to admire four volcanoes.

Mount Hood is on our left, in Oregon.

The Hood River starts here.

There are three volcanoes in this picture, all in Washington. The one in the

middle is Mount Adams. Mount Rainier is to its right, fainter because it's

47 miles farther away. Barely discernible at left is our objective for

Sunday's visit, Mount St. Helens ‐ also known as Loowit.

According to a legend of the Puyallup tribes,

Long ago a huge rock slide roared into the Columbia River and formed a natural stone bridge. The bridge came to be called Tamanawas, or Bridge of the Gods. In the center of the arch burned the only fire in the world, so of course the site was sacred to Native Americans. They came from north, south, west, and east to get embers for their own fires from the sacred fire.

A wrinkled old woman, Loowitlatkla ("Lady of Fire,") lived in the center of the arch, tending the fire. Loowit, as she was called, was so faithful in her task, and so kind to the Indians who came for fire, that she was noticed by the great chief Tyee Sahale. He had a gift he had given to very few others – among them his sons Klickitat and WyEast – and he decided to offer this gift to Loowit as well. The gift he bestowed on Loowit was eternal life. But Loowit wept, because she did not want to live forever as an old woman.

Sahale could not take back the gift, but he told Loowit he could grant her one wish. Her wish, to be young and beautiful, was granted, and the fame of her wondrous beauty spread far and wide.

One day WyEast came from the land of the Multnomahs in the south to see Loowit. Just as he arrived at Tamanawas Bridge, his brother Klickitat came thundering down from the north. Both brothers fell in love with Loowit, but she could not choose between them. Klickitat and WyEast had a tremendous fight. They burned villages. Entire forests disappeared in flames.

Sahale watched all of this fury and became very angry. He frowned. He smote Tamanawas Bridge, and it fell where the river still boils in angry protest. He smote the three lovers, too; but, even as he punished them, he loved them. So, where each lover fell, he raised a mighty mountain. Because Loowit was beautiful, her mountain (St. Helens) was a symmetrical cone, dazzling white. WyEast's mountain (Mount Hood) still lifts his head in pride. Klickitat, for all his rough ways, had a tender heart. As Mount Adams, he bends his head in sorrow, weeping to see the beautiful maiden Loowit wrapped in snow.

We became acquainted with the work of

Paul Kane four years ago when we visited

Rocky Mountain House on Alberta's North Saskatchewan River. After he passed

through Alberta, he continued to the Oregon Territory, where he sketched

Mount St. Helens. He later painted an eruption as seen from Spirit

Lake, based on stories he collected rather than actual observation. This is

one of the earliest images of Loowit's might made by a modern artist. It's

noteworthy because Kane put the eruption where it belonged, not on top of the

mountain.

We became acquainted with the work of

Paul Kane four years ago when we visited

Rocky Mountain House on Alberta's North Saskatchewan River. After he passed

through Alberta, he continued to the Oregon Territory, where he sketched

Mount St. Helens. He later painted an eruption as seen from Spirit

Lake, based on stories he collected rather than actual observation. This is

one of the earliest images of Loowit's might made by a modern artist. It's

noteworthy because Kane put the eruption where it belonged, not on top of the

mountain.

Now that we've reached western Washington, we'll adopt a much more

relaxed pace. Having crossed the continent in five days, we're about to

spend the next nine within 150 miles of Seattle.

But we didn't go to Seattle on this trip; there just wasn't time for that.

Our first stop is Chehalis, a good base for a visit to Mount St Helens.

You can't just land at the bottom of the mountain; it's a 60-mile drive from

even the closest motel.

Now that we've reached western Washington, we'll adopt a much more

relaxed pace. Having crossed the continent in five days, we're about to

spend the next nine within 150 miles of Seattle.

But we didn't go to Seattle on this trip; there just wasn't time for that.

Our first stop is Chehalis, a good base for a visit to Mount St Helens.

You can't just land at the bottom of the mountain; it's a 60-mile drive from

even the closest motel.

The operator at Chehalis named their terminal for Scott Crossfield, who grew

up nearby in Boistfort. Among many other accomplishments, Crossfield was the

first man to fly twice the speed of sound.

The operator at Chehalis named their terminal for Scott Crossfield, who grew

up nearby in Boistfort. Among many other accomplishments, Crossfield was the

first man to fly twice the speed of sound.

At dinner in Chehalis, we were greeted by an old favorite.

In the morning, we were greeted by a rocking bear at

Patty's Place, a recommended roadside stop on the way up to Mount

St. Helens. We ate on the back porch, with its fine view of the

Toutle River.

In the morning, we were greeted by a rocking bear at

Patty's Place, a recommended roadside stop on the way up to Mount

St. Helens. We ate on the back porch, with its fine view of the

Toutle River.

The State of Washington operates an interpretive center at Silver Lake.

One exhibit there is a diorama that helps the visitor get oriented to the

mountain and its surroundings. A short staircase leads beneath this display,

where there is a model of the magma chamber.

The State of Washington operates an interpretive center at Silver Lake.

One exhibit there is a diorama that helps the visitor get oriented to the

mountain and its surroundings. A short staircase leads beneath this display,

where there is a model of the magma chamber.

Another display shows several famous volcanoes, indicating how much

stuff they spewed.

Mount Mazama is in the middle, with the 36 cubic miles of material it ejected

about 7000 years ago to leave Crater Lake (Oregon) behind. St. Helens is

the tiny one front and center, having produced almost nothing by comparison.

The other two models in the front row are Krakatoa (1883) and Mount Katmai,

Alaska (1912). Don't underestimate this mountain. It has been the most active

volcano in the Cascades for the past 4500 years.

Another display shows several famous volcanoes, indicating how much

stuff they spewed.

Mount Mazama is in the middle, with the 36 cubic miles of material it ejected

about 7000 years ago to leave Crater Lake (Oregon) behind. St. Helens is

the tiny one front and center, having produced almost nothing by comparison.

The other two models in the front row are Krakatoa (1883) and Mount Katmai,

Alaska (1912). Don't underestimate this mountain. It has been the most active

volcano in the Cascades for the past 4500 years.

The 1980 eruption obliterated the old highway to St. Helens. When the road was rebuilt, it was relocated as much as possible to high ground. There is a marker on the new highway that tells the story.

Spirit Lake Memorial Highway (State Route 504)

Gateway to Mount St. Helens

On the morning of May 18, 1980, Mount St.

Helens erupted catastrophically and destroyed more than 30 miles of state

highway. Landslides and volcanic debris from 60 to 600 ft. thick filled

the valley bottom of the north fork of the Toutle River. The eruption

blew down more than 220 square miles of forest and affected engineering

works and navigation as far downstream as the Columbia River.

In 1982, the U.S. Congress established the Mount St. Helens National

Volcanic Monument to enhance public understanding, use and enjoyment of

the area. The Washington State Legislature designated State Route 504 as

"The Spirit Lake Memorial Highway" and dedicated it to the memory of the

57 people who lost their lives in the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

The new highway is located out of the valley bottom to avoid future

debris flows, minimize disturbance of natural remnants of the eruption

and avoid the sediment retention basin. Steep slopes, with highly

variable soil deposits, and bedrock challenged the geologists and

engineers involved in the exploration, design and construction of the

highway. Variable foundation materials required phased geotechnical

investigations, flexible designs and construction specifications based on

actual field conditions. Special design challenges required adjustment

of the road alignment to avoid debris flow, hazards and to stabilize

several large landslides, numerous rock slopes and materials that would

behave like a fluid and fail during earthquakes.

The sensitive ecosystem and unique landscape were protected and enhanced.

Road cuts and fills were minimized and more than 4000 feet of retaining

walls were constructed to protect the landscape. Construction wastes

were hauled from the monument. Utilities were placed underground.

Wetlands were bypassed or replaced and natural streams were bridged to

enhance the environment. To preserve the ecosystem, eagles were fed. An

elk calving area was shielded from the highway and native plants were

used for landscaping.

This outstanding environmental and engineering geologic project was

constructed between 1987 and 1994 through the joint effort of the

Washington Department of Transportation, the Federal Highway

Administration, and the U.S. Forest Service.

Dedicated October 1, 1998

We got our first view of Mount St. Helens from Hoffstadt Bluffs. You

can get a close look at the mountain from a helicopter tour that is based

here. The old Spirit Lake highway is fifty feet below today's river bed.

We got our first view of Mount St. Helens from Hoffstadt Bluffs. You

can get a close look at the mountain from a helicopter tour that is based

here. The old Spirit Lake highway is fifty feet below today's river bed.

When the highway was rebuilt, bridges had to accommodate its new elevation,

too. The Hoffstadt Creek Bridge is 2340 feet long and 370 feet high. The

terrain provided unique challenges in its construction. The usual temporary

support towers could not be used, so the bridge sections were cantilevered

from each side until they finally met in the middle.

When the highway was rebuilt, bridges had to accommodate its new elevation,

too. The Hoffstadt Creek Bridge is 2340 feet long and 370 feet high. The

terrain provided unique challenges in its construction. The usual temporary

support towers could not be used, so the bridge sections were cantilevered

from each side until they finally met in the middle.

The Forest Learning Center is affiliated with the Rocky Mountain Elk

Foundation, among others. There are telescopes there to give visitors a

better view of the elk sunning themselves on the gravel bars in the Toutle

River below. The elk apparently like that location because there are no

bushes there. Bugs live in the greenery, but they don't bother the animals

out in the open.

The Forest Learning Center is affiliated with the Rocky Mountain Elk

Foundation, among others. There are telescopes there to give visitors a

better view of the elk sunning themselves on the gravel bars in the Toutle

River below. The elk apparently like that location because there are no

bushes there. Bugs live in the greenery, but they don't bother the animals

out in the open.

A couple of miles farther along, we stopped at Elk Rock Lookout to get a view

of St. Helens with Mount Adams in the background.

David Johnston joined the U.S. Geological Service in 1978 after earning a doctorate for research in volcano geology. His special interest was to predict eruptions from fumarolic emissions – analyzing the content of gases emitted near volcanoes. The method was relatively new, but experts agreed that gas pressure and content were related to volcanic activity. Working with fellow geologist Don Swanson, Johnston helped to set survey reflectors on a bulge that was growing on the north face of Mount St. Helens in early 1980. They set up two observation posts on a ridge about six miles north of the mountain, called Coldwater I and II after a nearby stream. From there, they used laser ranging to monitor the bulge, which was growing five to eight feet per day just before the eruption.

Johnston was a key figure in establishing the boundaries of danger zones around Mount St. Helens. Residents were evacuated and logging operations suspended. Although the people whose lives were interrupted resented several weeks of government intrusion, this action saved thousands of lives.

Harry Glicken was a graduate student working for the U.S. Geological Survey

in 1980.

He manned the

Coldwater II observation post for two and a half weeks before

the eruption. Because of a job interview, he needed to be relieved just

before that fateful Sunday morning. It was David Johnston who relieved him,

and Glicken never quite got over the coincidence.

Glicken took this picture of his colleague

just before leaving Coldwater II. Fourteen hours later,

Dave Johnston was buried alive while reporting the eruption.

Harry Glicken was a graduate student working for the U.S. Geological Survey

in 1980.

He manned the

Coldwater II observation post for two and a half weeks before

the eruption. Because of a job interview, he needed to be relieved just

before that fateful Sunday morning. It was David Johnston who relieved him,

and Glicken never quite got over the coincidence.

Glicken took this picture of his colleague

just before leaving Coldwater II. Fourteen hours later,

Dave Johnston was buried alive while reporting the eruption.

The ridge was renamed Johnston Ridge, and two years later the USGS dedicated the David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory on the site of Coldwater II. This building is at the end of the Spirit Lake Memorial Highway. Most visitors are not aware of the scientific work done there by about 100 technical staff because of the size of the interpretive displays, gift shop, and auditorium inside.

While we were at Johnston Ridge, we listened to a ranger talk about the

eruption, its geology, the preparation before it and the massive recovery

that followed. Then we went into the auditorium for an excellent film about

the subject.

When the movie finished and the lights came up, the screen went up too,

revealing a very large window.

Of course, we could simply walk back outside, where Loowit watches

serenely over Coldwater II.

This is a wide photo. If you'd rather see a smaller version, it's

here.

Here is the

same view of the mountain, from the same spot, one day before the

1980 eruption.

This photo was also taken by Harry Glicken.

Ironically, Glicken was

killed by a volcano eleven years after he escaped death here, when

he couldn't get away from pyroclastic flow beneath Japan's Mount Unzen.

Johnston Ridge is viewed from a turnout just below the end of the road.

Trees here have been left where they fell in 1980.

Johnston Ridge is viewed from a turnout just below the end of the road.

Trees here have been left where they fell in 1980.

This sign explains a curious phenomenon. Observers on Mt. Adams, 33

miles away, saw St. Helens's eruption but heard nothing. Others, out of

sight and hundreds of miles away, heard the violence clearly. The pressure

patterns associated with the eruption acted as an acoustic lens, directing

the sound upward. When the acoustic energy reached the stratosphere, a

permanent temperature inversion reflected it back to earth. This effect

produced alternating rings of loudness and quiet. There was a silent zone of

about 60-mile radius; sound was loudest between 150 and 200 miles distant.

The farthest location where the eruption was heard, was a Canadian town 690

miles away.

This sign explains a curious phenomenon. Observers on Mt. Adams, 33

miles away, saw St. Helens's eruption but heard nothing. Others, out of

sight and hundreds of miles away, heard the violence clearly. The pressure

patterns associated with the eruption acted as an acoustic lens, directing

the sound upward. When the acoustic energy reached the stratosphere, a

permanent temperature inversion reflected it back to earth. This effect

produced alternating rings of loudness and quiet. There was a silent zone of

about 60-mile radius; sound was loudest between 150 and 200 miles distant.

The farthest location where the eruption was heard, was a Canadian town 690

miles away.

There is a path through the woods on new earth that was deposited in the

avalanche that came with the eruption. The photographer is standing on earth

that got here from the mountainside six miles away, in about two minutes.

The hummocks along this trail are made of the same material as found in

St. Helens's crater in the distance.

There is a path through the woods on new earth that was deposited in the

avalanche that came with the eruption. The photographer is standing on earth

that got here from the mountainside six miles away, in about two minutes.

The hummocks along this trail are made of the same material as found in

St. Helens's crater in the distance.

This happened in three stages. First, a large block broke off the left side

of the mountain and slid over here. A few seconds later, another block broke

off behind it, pushing the first one across the valley. The third block to

break away tumbled down behind the first two. The soil on the present

mountain came from the eruption.

This happened in three stages. First, a large block broke off the left side

of the mountain and slid over here. A few seconds later, another block broke

off behind it, pushing the first one across the valley. The third block to

break away tumbled down behind the first two. The soil on the present

mountain came from the eruption.

Spirit Lake sat on the north face of the mountain. Since 1926, Harry Truman had been the caretaker of the Mount St. Helens Lodge on the lake. When the area was evacuated, Truman refused to leave his home and his sixteen cats. 84 years old and stubborn as his namesake, he was the only "non-essential" person given permission to remain within the blast zone.

The eruption buried Spirit Lake. Like David Johnston, Harry Truman vanished without a trace.

The same debris that buried Spirit Lake dammed the river and reformed the lake, 210 feet above its former level. With no outlet from the lake, there was now a danger of flooding, so a pump station and pipeline were built. Now Spirit Lake is once again the source of the North Fork of the Toutle River. Some of its water also feeds Coldwater Creek.

Coldwater Lake didn't exist before the eruption. Ash settled here and formed

a delta. When the tunnel from Spirit Lake was opened here, the new flow

opened a wider channel, carrying a lot of sediment away.

Coldwater Lake didn't exist before the eruption. Ash settled here and formed

a delta. When the tunnel from Spirit Lake was opened here, the new flow

opened a wider channel, carrying a lot of sediment away.

This brought new risk of flooding, so workers made a new channel and natural

dam to contain the lake at the size we see today. It's now a popular

recreation area, complete with campground.

This brought new risk of flooding, so workers made a new channel and natural

dam to contain the lake at the size we see today. It's now a popular

recreation area, complete with campground.

Not far away, Castle Lake was also formed after the 1980 eruption.

The Tree Planter

The Tree Planter

Georgia Gerber

The Forest Learning Center, where we watched elk basking, is managed by

Weyerhaeuser Corporation. The avalanches dealt them a heavy economic blow,

but they started to work right away. First, they recovered as much timber as

they could, then they began replanting.

Over a seven-year period, company workers planted 18 million seedlings in a

70-square-mile area. There are no machines for this; all of those trees were

planted by hand.

Over a seven-year period, company workers planted 18 million seedlings in a

70-square-mile area. There are no machines for this; all of those trees were

planted by hand.

This display compares the size of managed trees with natural growth, which is more crowded.

These trees were

planted at Hoffstadt Bluffs in remembrance of the 57 people

whose lives ended when Mount St. Helens exploded in 1980. A plaque by

the walkway

reads,

This memorial grove is

Dedicated

To those who lost their

Lives in the May 18, 1980

Eruption of Mount St. Helens

"Loowit"

| Robert Landsburg | Christy Killian |

| James Fitzgerald | John Killian |

| Arlene Edwards | Don Selby |

| Jolene Edwards | Klaus Zimmerman |

| Barbara Seibold | Harold Kirkpatrick |

| Ronald Seibold | Joyce Kirkpatrick |

| Michelle (Seibold) Morris | Joel Colten |

| Kevin (Seibold) Morris | Paul F. Schmidt |

| Margery Rollins | Wally Bowers |

| Fred Rollins | Ellen Dill |

| Bill Parker | Robert Dill |

| Jean Parker | Bruce Faddis |

| Clyde Croft | Tom Gadwa |

| Terry Crall | Paul Hiatt |

| Karen Varner | David Johnston |

| Reid Blackburn | Bob Kaseweter |

| Allen Handy | Robert Lynds |

| Don Parker | Gerry Martin |

| Natalie Parker | Keith Moore |

| Rick Parker | Eleanor Murphy |

| Day Karr | Ed Murphy |

| Michael Karr | Kathleen Pluard |

| Andy Karr | Merlin "Jim" Pluard |

| Ron Conner | Doug Thayer |

| Gerald Moore | Harry Truman |

| Shirley Moore | James S. Tute |

| Evlanti Sharipoff | Velvet Tute |

| Jose Dias | Beverly Wetherald |

| Leonty Skorohodoff |

Dedicated May 18, 2000

on to Toledo

Michigan City

Sioux Falls

Billings

EBR-1

Home