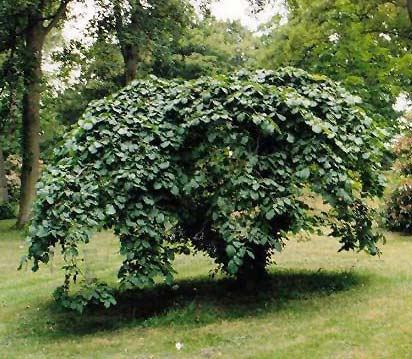

Ulmus glabra Camperdownii

David Taylor was a forester employed by Robert Haldane-Duncan [1], the First Earl of Camperdown in Dundee, Scotland. One day in 1840, he noticed a mutant Scotch Elm (Wych Elm) that was "creeping along the ground amongst other elms." Although Mr. Taylor didn't realize it, this sport tree was missing the gene for negative geotropism. In other words, it "didn't know which way was up," and hugged the ground rather than growing tall. He transplanted this contorted tree to the Earl's gardens, where it still lives. He was inspired to graft a cutting from this tree to the trunk of a normal Wych Elm, making the first Camperdown Elm, also called Umbrella Tree or Upside-down Tree because of its shape. The branches grow outward and tend to "weep," instead of growing tall like a normal elm.

photo by Rosser1954

The mutant cannot reproduce, so every Camperdown Elm in the world is a direct descendant of the original sport in the first photograph, made by the same kind of graft used by David Taylor almost 200 years ago. The graft line is distinct, showing different types of bark on either side. It is usually 4 to 6 feet above ground.

The Camperdown Elm is an unusual tree, but it isn't rare. It was a sought-after addition to Victorian gardens, so there are quite a few notable specimens here and there, most of them over one hundred years old. These are a few examples. Many were placed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the pioneer landscape architect.

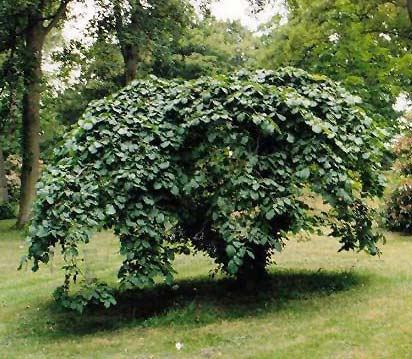

After their success with Manhattan's Central Park, Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux collaborated in the thirty-year evolution of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, from 1865 to 1895. Inspired by the Victorian passion for the tree, Brooklyn florist A.G. Burgess gave a Camperdown Elm to the Brooklyn Parks Commission in 1872. Despite his ambivalence about the tree, Olmstead placed it near the boathouse on the Lullwater. The graft was rather low on the root stock, so he planted the tree on a small hill to leave plenty of room for its drooping branches. In short order, the tree became an icon of the park, not least because of the twisted, romantic path its branches took as they grew.

photo by Jim and Janine Eden (Edenpictures)

The Prospect Camperdown invites visitors to climb it, which is no longer permitted because the tree weakened as it was almost lost about fifty years ago.

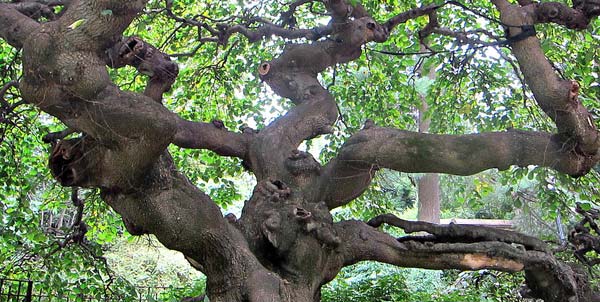

photo by Allison Meier

By 1965, Prospect Park's famous elm tree was in terrible shape. The tree was afflicted with slime flux, a bacterial infection; and many parts had been hollowed by rats, carpenter ants, and rot. This was a depressing period in New York City history, with rising crime, and a general attitude that the city itself was dying. The fate of one individual tree didn't seem very important.

Then it came to the attention of Marianne Moore, a famous poet who lived nearby. Miss Moore had already won the Pulitzer Prize for her work, as well as the National Book Award and other honors. She was also president of New York's Greensward Foundation. Her advocacy led her to form the Prospect Park Foundation, which aimed to care for all of the park's endangered trees. She wrote a poem that rallied people to the cause of the parks trees, its Camperdown Elm especially.

Miss Moore's reputation and her poem produced public support and helped to raise money to save the tree. When she published the poem, she asked that people donate money to save the tree instead of sending flowers to her funeral, which she presumed was imminent (she was almost 80 years old). The internationally renowned Bartlett Tree Experts were engaged to do what they could. They filled several holes, removed dead wood, and installed cables to support its branches. The work paid off, and the tree is healthy today. When the poet died, her will endowed the Marianne Moore Remembrance Fund to help support this and other trees in the park.

Her poem was published in The New Yorker in September 1967:

I think, in connection with this weeping elm,

of "Kindred Spirits" at the edge of a rockledge

overlooking a stream:

Thanatopsis-invoking tree-loving Bryant

conversing with Thomas Cole

in Asher Durand's painting of them

under the filigree of an elm overhead.

No doubt they had seen other trees — lindens,

maples and sycamores, oaks and the Paris

street-tree, the horse-chestnut; but imagine

their rapture, had they come on the Camperdown elm's

massiveness and "the intricate pattern of its branches,"

arching high, curving low, in its mist of fine twigs.

The Bartlett tree-cavity specialist saw it

and thrust his arm the whole length of the hollowness

of its torso and there were six small cavities also.

Props are needed and tree-food. It is still leafing;

still there. Mortal though. We must save it. It is

our crowning curio.

Marianne Moore

Kindred Spirits (1849), by Asher Brown Durand

When Marianne Moore wrote The Camperdown Elm, this painting was displayed in the New York Public Library. Art patron Jonathan Sturges had commissioned it as a gift to William Cullen Bryant (left) after hearing his funeral eulogy to Thomas Cole (right, with hat and sketchpad). Thanatopsis is considered to be Bryant's most notable poem. Cole founded the Hudson River School of 19th-century artists, which included Durand.

[1] Adam Duncan was the Scottish admiral who defeated the Franco-Dutch Fleet in bold action off Camperdown in 1797. The significance of this event has been compared to that of the more familiar Battle of Britain. Consequently, he was raised to peerage as Viscount Duncan of Camperdown, thereby acquiring a large parcel of land in Dundee. It was widely held that the honor was not enough for the service he had given the Crown, so his eldest son Robert was named Earl of Camperdown in 1831. Robert assumed the additional surname Haldane, a family name on his mother's side. When the 4th Earl of Camperdown died childless in 1933, the title became extinct. Only the trees are left to carry on his name.

[2]

Several years ago, a discontented gardener who was fired tried to kill these

trees by cutting rings through the cambium layer. (This is not the graft line

– note the continuity of the bark pattern above and below it.) To

everyone's amazement, the trees have survived.

[2]

Several years ago, a discontented gardener who was fired tried to kill these

trees by cutting rings through the cambium layer. (This is not the graft line

– note the continuity of the bark pattern above and below it.) To

everyone's amazement, the trees have survived.

[3] Planted about 1917 by John C. Olmsted, adopted son of Frederick Law Olmsted.

[4] This tree was almost doomed because it was in the way of construction for an athletic field. A generous individual donated over $100,000 to move the tree 90 feet to a better spot. This was done in 2013, and the tree appears to be doing well.