Home

—

More Articles

This article is transcribed verbatim (a few misspellings have been corrected)

from Today's Sunbeam, a Salem (N.J.)

newspaper that ceased publication in 2012. The footnotes are not original.

19th Century Jewish Colonists Had a Great Impact

by G. Thomas Bowen

11 February 1975

This is the year of the 300th anniversary of the founding of John Fenwick's

colony at Salem. And there is new emphasis on the "culture and heritage" of

this and all New Jersey communities.

It's a good time to remember that the vitality of culture and heritage in

America is derived from a variety of roots or patterns brought here by

different bands of colonists in different periods.

One very small group which came to Salem County in 1882 had an impact which,

like the Quakers before them, was disproportionate to the small numbers of

people involved.

It was the pilgrimage of Jews who founded the "colonies" of Alliance, Norma,

Garton Road, Carmel, Rosenhayn and Brotmanville in Pittsgrove Township.

These unusually named little towns between Bridgeton, Vineland, and Millville

remain untouched by the growth as well as the problems which beset much of

New Jersey and the nation. Nor can there be found the charming colonial

buildings erected by Quakers. But the Jews likewise fled from an

inhospitable Europe, and the richness of American life owes much to them.

Russian Jews escaping persecution sought a new life in South Jersey

Their story begins not with the restoration of the monarchy under

Charles II in England, but with the Russo-Turkish War and the

assassination of Czar Alexander II in Russia. The war lasted from 1878

to 1881, and the aftermath was the "pogroms," a systematic destructory and

harassment of Eastern European Jews.

Leaving their homelands, the Jews, like the English pilgrims, yearned to go

"back to nature." One group went to Palestine; the other came to the United

States.

Most of those who came, several million of them, poured into the already

crowded tenements of New York. But several international Jewish cultural and

relief societies — the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and Alliance

Israélite Universelle — had a better idea.

The dream of their leaders was to start small agricultural colonies for

assimilation into American life. Farming had been denied to Jews in Europe,

and a new opportunity to engage in this dignified and traditional livelihood

seemed to be the ideal means of achieving a fresh start in a new land.

With this in mind, scouts were sent to look over the area between Bridgeton,

Vineland, and Millville, including Deerfield Township in Cumberland County

and Pittsgrove Township in Salem County. There was access to the railroad to

New York and also to the markets in Philadelphia. Moreover, land was cheaply

available.

Men, and later their families, were sent from Ellis

Island and other

temporary quarters. They found life in the new world indeed severe. The

fields had to be cleared of trees and rocks, often without the aid of horses.

The land in many areas was sandy, and only reluctantly yielded crops. They

knew little or nothing about farming, since many of the first settlers had

left well-paying professions in Europe. Like the English pilgrims, they

brought only their piety and willingness to work.

Alliance

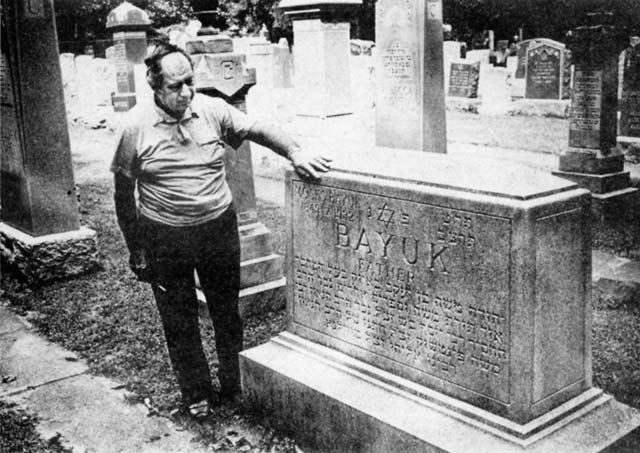

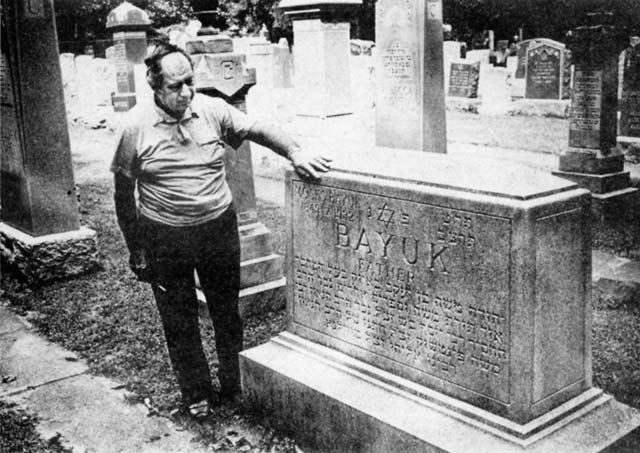

In Alliance Cemetery,

I. Harry Levin, Municipal Judge for Pittsgrove Township, contemplates

the grave marker of his grandfather, Moses Bayuk, one of the founders of the

Jewish colony which they named Alliance. Moses Bayuk had been a lawyer in

Russia and was a Talmudic scholar. His sons founded the nationally known

Bayuk Cigar Company.

Alliance was named after its sponsoring organization, Alliance Israélite

Universelle. Moses Bayuk, who together with Eli Stavitsky chose the site for

Alliance, was typical of the early settlers. A lawyer and Talmudic scholar,

he wrote five volumes of commentaries on the Old Testament and served as

justice of the peace while struggling to build an agricultural community in

his new land. Typical, also, were the paths chosen by his descendants. His

sons became cigar makers and built the huge Bayuk Cigar Company in

Philadelphia. His son-in-law William Levin became a farmer, and Levin's son,

I. Harry Levin became a lawyer and collector of Jewish memorabilia.

I. Harry Levin is the municipal Court Judge for Pittsgrove Township in

Salem County, and his son, too has followed his father into the practice of

law.

In accordance with the format adopted by most of the colonies, a corporation

was formed at Alliance, the land was surveyed, and then divided into 15-acre

plots. Each plot was given a number, and each family drew a number, assuming

the obligation to clear the chosen plot. The corporation took a purchase

money mortgage for one hundred forty dollars.

Alliance was located near the railroad station known as Bradway Station,

after the Bradway family which had settled the area before the arrival of the

Jewish immigrants. When land was added to Alliance about 1900, the new area

was named Norma, in honor of a daughter of the Bradway family. A synagogue

was built at Norma, to comply with orthodox Jewish law that a synagogue must

be within a few hundred yards walking distance.

The second synagogue supplemented Sharis Israel

Synagogue

at Alliance, organized soon after the birth of the colony in 1882, and built

largely from donations from the wealthy New York Jew, Jacob Schiff.

Later, another settlement was established nearby at Six Points, so named

after the six roads which intersected at the site. Eskintown grew from

houses built to accommodate workers in a brick factory built by Morris Eskin.

Still another settlement was called Brotmanville, after Abraham Brotman, who

established a large sewing factory.

One of his descendants is Stanley Brotman, an attorney in Vineland who is

serving as President of the New Jersey Bar Association and who has just been

nominated as a U.S. District Court Judge for New Jersey.

Such industries were necessary to sustain the settlers, who tilled the

general poor soil without the assistance of capital or extra labor. Clothing

was made for wear or resale at home, and homes were barely heated at all

during the hard winter months.

Sons and daughters left the tiny colonies to fill prominent positions in

American life

In spite of such modest beginnings, the children of the settlers studied

while they helped till the land and worked in the factories. Many grew up to

be prominent Americans. George Seldes, the internationally known literary

critic, came from a family living at Alliance; his brother Gilbert Seldes

became the first Dean of the Annenberg School of Communications at the

University of Pennsylvania. Joseph B. Perskie, the first Jewish New Jersey

Supreme Court Justice, came from Alliance; his brother Jacob Perskie became a

noted artist and photographer who did a famous portrait of Franklin

Roosevelt. The Agronsky family of Alliance produced Martin Agronsky, the

television commentator, as well as Gershon Agronsky, a premier of Israel and

founder of the Jerusalem Post, Israel's foremost English language

newspaper.

Carmel

Columbia Hall

in Carmel is one of the community centers where Louis Mounier taught cultural

subjects to local people of all ages. There was a library and study room on

the first floor. At left is the present Carmel Fire House.

Michael Heilprin, founding leader of Carmel in Deerfield Township, fled from

Poland to the United States in 1856. In 1882 he brought some Eastern

European pioneers to the spot where the Bridgeton to Vineland road crossed

the Philadelphia to Cape May highway. Like a number of pioneers, Heilprin

was knowledgeable in history and philosophy, and was said to be conversant in

twelve languages. The descendant of a rabbinical family of Hebrew scholars,

he continued the tradition of biblical scholarship in the new land.

The settlers at Carmel, like those in the other colonies, were assisted in

their early struggles by the societies which had sent them, and by wealthy

Jews like Baron de Hirsch, a European railroad builder. The primary creator

of the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society as well as the Baron de

Hirsch Fund, de Hirsch provided low-interest mortgages, language and

agricultural classes and myriad other services.

The societies helped the Carmel settlers build a public hall, which served as

the site of dances, theatrical performances and classes. Columbia Hall, built

next to Beth Hillel Synagogue, also contained a library where the townspeople

could continue their learning.

Another center of community life at Carmel was the mikvah, an institution

brought to the colonies from the old country. A communal bath, it served

social and religious as well as hygienic purposes. During the hot summer,

residents paid two cents to talk and argue in the men's and women's

bathhouses erected over Lebanon Stream.

The American pastime of baseball is the diversion for which Carmel is today

remembered throughout South Jersey. Everybody came out on Saturday afternoon

to view the game, and the skill of the players as they played teams

throughout the area brought honor to the community.

Ted Rosen was a local boy who shared with other colony residents a strong

sense of patriotic devotion to America. He distinguished himself mightily on

the battlefield as a captain in World War I, suffering a number of grave

injuries. After the war, he became an important national leader of the

American Legion. Rosen also became a respected member of the bench in

Philadelphia, sitting as a Court of Common Pleas judge. Today, a simple

monument in his memory stands next to Columbia Hall in Carmel.

Nor is Carmel without its share of other distinguished citizens. Ted Rosen's

brother Raymond established a huge electrical supply distribution center in

Philadelphia. Joseph Narrow serves as Salem County judge, carrying on the

tradition of his father. who served as a beloved and respected lay arbiter of

Carmel disputes.

Remaining at home, Morris April, who during his career ran a country store in

the front of his house, has operated with his family the orchards which

produce some of the area's fine fruits. Morris' wife Lillian has been

active in the community's cultural and educational life. As a tribute to her

services, the Lillian April School today houses local students.

Other prominent Carmel citizens include James Kohn, who became a prominent

Philadelphia attorney, and the writer George Rolands, whose brother was a

professor at Columbia University.

Abraham Kazan, once a worker in Henry Dix's clothing factory in Carmel, also

made his mark in American life. A participant in a factory strike organized

by young socialist workers, Kazan was ordered to leave Carmel. He was sent

to New York, funded by three dollars given him by his fellow workers.

In New York, Kazan became a statistician for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers

Union. He started a co-op food store for union workers in New York City,

then supervised the construction of a huge co-operative apartment complex for

workers. Legend has it that he became acquainted with John D. Rockefeller,

Jr. while riding the train to Albany to lobby for benefits for workers. At

any rate, he ultimately supervised the gigantic reconstruction project of the

East side of New York City, a project of the Rockefeller Foundation.

Garton Road

Beth Israel Synagogue,

at Garton Road, was built around 1900.

Isaac Serata came to the colony called Garton Road from Kiev in the Ukraine.

A big, strapping man, he cleared and farmed successively larger areas. While

some of the land stubbornly resisted cultivation, much of it yielded fairly

good harvest of fruits and vegetables, and his fellow settlers shared the few

horses they owned to plow each other's land.

Serata amassed a large farm operation and later started a business of

processing Kieffer pears by smoking them. He also became an important

produce broker. Gifted with great ambition and vitality, he became a

director of the bank founded by Harry Woodruff, from the neighboring

Methodist village of that name which shared cultural life with Garton Road.

The bank later became the Farmers' and Merchants' Bank of Bridgeton.

Although Serata saw his fortune dwindle when canning replaced the smoking

process, he turned to other ventures and became a highly successful seed,

feed, and coal dealer. In his later years he became a member of the

Philadelphia Bourse.

Serata had been joined in the new land by Chuna

Adler,

who came from Kiev

three years after Serata as a result of an exchange of letters between the two

men. Both men were abundantly possessed of strength and endurance, and each

weathered his first season without a family, building a rough shelter and

enduring the cold, heatless winter.

Former Cossack kept peace in choosing synagogue chores

Adler was known for his fair-mindedness as well as his strength, and for many

years the duty of serving as Gabbai in the synagogue fell to him. That duty

consisted of choosing the reader at services. Adler's visible strength

thwarted many a quarrel over who would do the reading, according to his son,

Harry Adler, Sr., a retired judge of Cumberland County. Adler allows that

his reputation for having served with the Cossacks in the Ukraine probably

did his father no harm, either. But Adler believes it was his father's

reputation for absolute impartiality that caused his fellow colonists to

listen to him. Adler himself, like Judge Narrow in Salem, continued the

family tradition and gained the reputation as a compassionate but fair

decision-maker.

Another who joined Serata at Garton Road was Abraham Ostroff, whose son

Samuel operates with his family a poultry farm next to Beth Israel Synagogue,

now open only on holidays. Ostroff remembers the robust cheerfulness of the

early settlers like the Moses Sherbekow family; everyone helped each other

for worship on the sabbath. "Not like now," he notes ruefully, "when

everyone shifts for himself and for no one else."

Rosenhayn

At about the same time as the founding of the other colonies, Hyman Schrank

and his colleagues travelled from the border area of Germany and Austria to

the colony which became known as Rosenhayn. Like those in the other

colonies, they farmed the land and also worked in the small industries which

supplemented their meager crops.

Rosenhayn had a brickyard, a small iron foundry, a hide and tallow plant,

sweater factories, and factories making men's suits and coats. Out of such

labors grew Joseph Brothers, a large manufacturing concern whose founding

family also includes a retired jurist, Judge Arthur Joseph of Cumberland

County.

Max Schrank developed his clothing factory with headquarters in Bridgeton

into an internationally known company, M.C. Schrank Company. Mr. Schrank's

brother Albert, a retired executive of the company, still lives in Bridgeton.

The Stotter family developed the prominent hospital supply company bearing

its founder's name, Leon Stotter, who still operates it, assisted by his

brother Milton.

Like other colonies, Rosenhayn had its cultural center, Franklin Hall,

housing a public hall and library.

The colony also had a newspaper, "The Rosenhayn Advocate." Its August 24,

1894, issue informed residents of local gossip and home cure remedies, as

well as international issues of the day — a long article describing the

exotic nation of Korea, then fought over by Japan and China, gave local

residents a course in international affairs.

French professor hired to teach colonists language, literature, and ways of

American life

Louis Mounier

was a French portrait painter who had lived in New York City and retired to

Vineland. He was employed by the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid

Society to teach cultural subjects in the Salem and Cumberland County

communities.

Cultural life and a thirst for learning was an integral part of life in all

the colonies. To promote this interest, the Jewish Agricultural and

Industrial Aid Society brought to South Jersey one of its most colorful

teachers, Professor Louis Mounier.

Professor Mounier had come to the United States from France in 1873, bringing

with him a background in painting, music, history, and a strong sense of

idealism. He had retired to Vineland for the sake of his health with his

wife Louise and daughter when representatives from the Jewish Agricultural

and Industrial Aid Society approached him with the offer to teach at the

colonies.

Upon accepting, he and his wife devoted one day each week to each colony. He

sang and played the cello and his wife played the piano. He showed slides of

cultural and natural landmarks on his magic lantern, organized art classes,

and also gardening classes for the children. Albert Schrank fondly remembers

winning a trip to Trenton to exhibit his prize crops.

Professor Mounier's ambitious program also involved organizing dances and

entertainments featuring prominent Jewish and non-Jewish celebrities of the

period. The famed writer of Yiddish humor, Sholem Aleichem, visited the

colonies through Mounier's efforts.

Another source of culture at the colonies, and a source of income as well,

were the summer boarding houses. They began on an informal family basis,

when New Yorkers journeyed on the train to the farms of friends and relatives

to escape the oppressive city heat. They came with such regularity that the

farmers' children had a hard time claiming their share of food at the table.

So boarding houses were turned into business enterprises. One such

establishment was that of Aaron Rodesky in Garton Road.

Often the summer visitors were actors or other "intellectual bohemian types,"

who, according to Harry Adler, were suspected by the local families of being

lazy and, maybe, altogether worthless. But other residents were highly

intellectual themselves, and Adler recalls that they had a great time

visiting with the guests. The Israeli National Anthem, "Hatikvah," was

written by Naftali Imber, while staying at the boarding house at the

Weinblatt farm.

Other visitors were the family of Muni Weisenfreund, who

later became famous as the actor Paul Muni.

Today, the hotels are gone, the children have moved away, and the colonies

are mostly quiet, except for occasional return visits to the synagogues. In

many areas, a later wave of Italian and Sicilian immigrants have bought the

farms. But the colonies served their purpose well, providing an entry place

for dedicated immigrants into the mainstream of American life.

Notes

The reference should probably be to Castle Garden, an entry station at the

southern end of Manhattan. The entry station at Ellis Island did not open

until 1892.

Also known as

Tifereth Israel.

Also known as Kaan Adler.

This story is apocryphal. According to more reliable sources,

Imber wrote the poem that became Hatikvah in 1877 or 1878, in Romania.